Justice Railroaded

As the turn of the new millennium came and went, there was a story that should have made headline news but raised hardly a peep from legacy media.

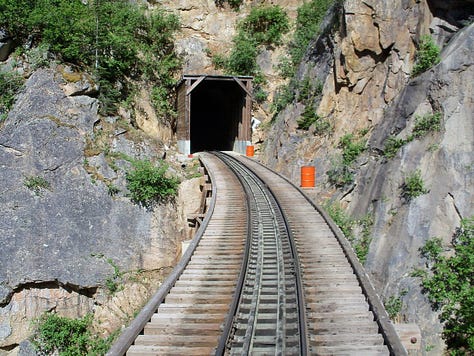

By the thousands they came, the gold-seekers of 1897, pouring through Alaska’s White and Chilkoot passes on their way to the Klondike and to fortune. Fast behind them came the entrepreneurs, the bunco artists, and before long, the engineers and financiers whose driving ambition was to build a railway through the White Pass’s rocky precipices.

Roy Minter, author The White Pass: Gateway to the Klondike

Words 1,985 | Read Time 9 min | Enjoy

Introductionary Summary

As the new millennium began, a significant yet largely overlooked story emerged involving an individual’s incarceration for environmental harm. This case, which should have stirred legal rights advocates, highlights a growing trend where managers are prosecuted for their companies’ actions, even when they are carried out by employees contrary to instructions. This situation arises from federal laws that have removed the criminal intent requirement, particularly in the “public welfare” legislation encompassing healthcare, antitrust, and environmental statutes.

The case of United States vs. Edward Hanousek, a Pacific & Arctic Railway and Navigation Company manager, illustrates this issue. Hanousek was criminally charged and served time for an environmental incident in 1994 despite being off-duty at the time. An employee of a contractor inadvertently caused an oil spill by damaging a pipeline with a backhoe, but Hanousek was held responsible due to his managerial position.

Hanousek’s defense contended that criminal penalties for simple negligence under public welfare laws violate due process. Still, the court maintained that such laws are necessary to protect the public from pollution. The appellate court upheld the conviction, emphasizing the stringent nature of these laws.

This case raises questions about the balance between environmental protection and individual rights. It calls for reassessing the current legal framework to ensure fairness and reasoned measures in environmental legislation, reflecting on whether the extreme zeal for environmental protection sometimes undermines fundamental human rights.

United States v. Hanousek

An important story occurred as the new millennium emerged. But it raised hardly a peep from the mainstream media. This story should have caused a stir among those who clamored for the legal rights of those facing charges. So, what was this problem? It is about a person incarcerated for harming the environment. It’s all about the “environmental justice” whirlwind, with some saying, “Frederick, so what.” Please stay tuned.

More and more managers face prosecution for their companies’ actions. What’s even worse is that some managers face charges for the actions of their employees. That happens even if the employees act against instructions or company policy. It is possible because more criminal laws have eliminated the aspect of intent to prosecute.

Since many federal laws deal with items considered “public welfare,” lawmakers have this acid in mind. Examples of criminal intent removed for the “public welfare” include healthcare statutes. They also include laws about the environment and antitrust. As usual, the main culprit is the federal government.

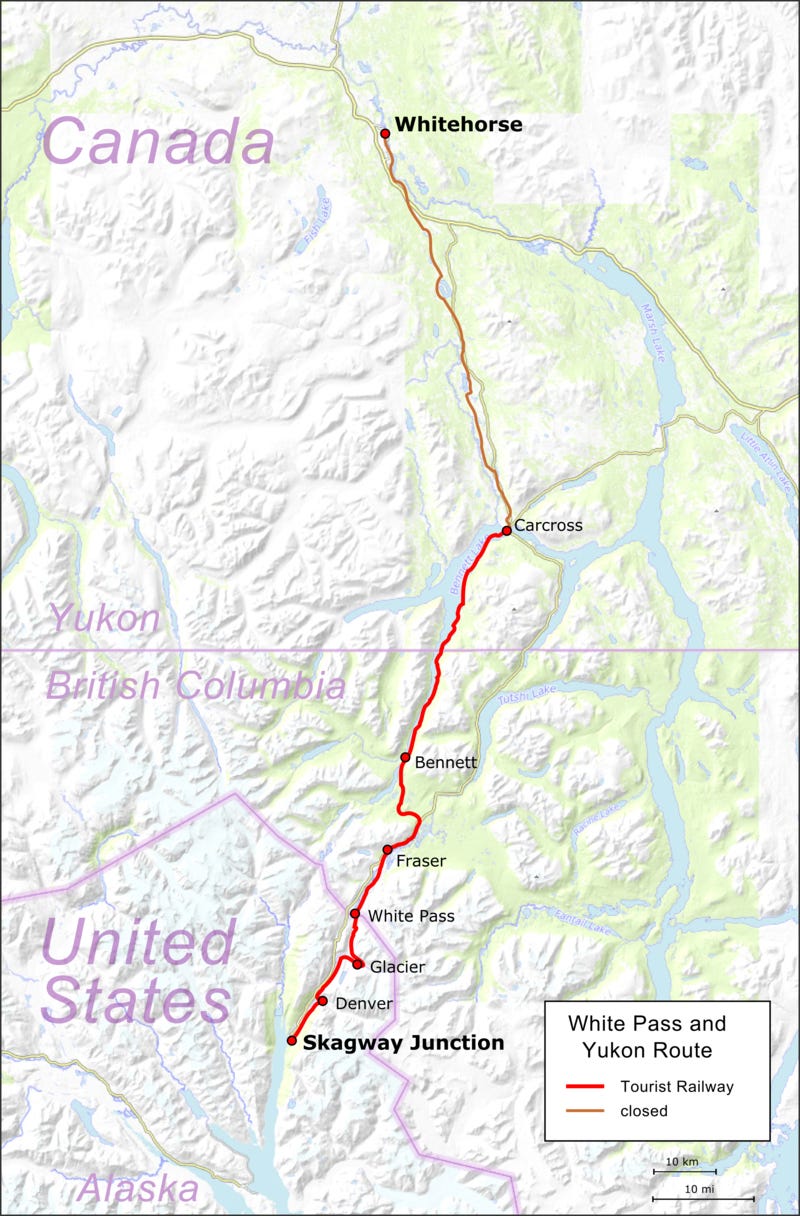

Enter the United States vs. Edward Hanousek, a Pacific & Arctic Railway and Navigation Company manager. This company does business as the “White Pass and Yukon Route” (WP&YR), and Hanousek was a “roadmaster.” His responsibilities included maintaining railroad tracks, wayside structures, and marine facilities. Are you ready to know about the “horrendous” crime that this roadmaster committed? Mr. Hanousek faced criminal charges and served time for damaging the environment in 1994. This may be understandable for those who worship Mother Gaia, but the devil is in the details.

The government has been excessive in its treatment of the environment. Yet, the key fact in this case is that Mr. Hanousek was not on duty. He was at home when the incident occurred. To add insult to injury, an employee of a railroad contractor caused the incident. Since Mr. Hanousek managed this operation, prosecutors named him the responsible “party.”

Under Hanousek’s direction, the project was a rock quarrying effort at a site next to the railroad known as “six-mile” (Milepost 6). This area is 200 feet above the Skagway River, and the project involved removing rock and outcroppings alongside the railroad. Workers moved the loose rock from the track using a backhoe to load it onto railroad cars. At Milepost 6, Pacific & Arctic’s sister company owns a high-pressure petroleum pipeline. The Pacific and Arctic Pipeline runs next to the railroad a few feet from the tracks. During the rock-clearing operation, the backhoe accidentally hit the pipeline. That caused 1,000 to 5,000 gallons of heating oil to flow into the Skagway River in Alaska. The term “accident” has no meaning in the minds of environmental extremists. Are all people in car crashes charged with an environmental crime? Where are these same people when it comes to the damage to the ecosystem and wildlife during the construction of offshore wind farms? Or, what about the harm to the crust from mining rare minerals for electric vehicle batteries?

Remember, Hanousek was off-duty at the time. Yet, he spent six months in prison for failing to supervise the worker in a “proper” manner. This failure was the “direct cause” of the oil spill. In sane times, the railroad would have been liable for accident damages. But we have blurred the line between civil liability and felony. Rest assured, the environmentalists see this damage to the environment of Alaska to be worse than murdering a person. Thus, authorities charged Hanousek. They convicted him under the Clean Water Act for the discharge of oil into a US waterway. Besides jail, he faced a $5,000 fine and six months in a halfway house. Finally, he faced six months of supervised release. And the government and its symbiotic elites wonder why some people become “anti-government.”

Hanousek’s lawyers argued that a public welfare law has criminal penalties for simple negligence. In this case, it was an accident. They said this violates due process. Still, the court emphasized the criminal parts of the law that make up “public welfare” legislation. It protects the public from the results of water pollution. The court declined to instruct the jury that the defendant was not responsible for the operator’s actions. This case involved an oversight at worst, but it turned into a criminal case. Also, the appellate court found that the jury instruction was too short. It told the jury to find that the defendant’s conduct had a “direct and big” link to the incident. The appellate court upheld the decision despite the above factors. These harsh “public welfare” laws can jail those with indirect involvement.

Where are the social justice warriors? They clamor about the rights of “poor criminals.” Crickets. The stalwarts of equality believe that the WP&YR case is important. Thus, the environment trumps human rights.

Meanwhile, the St. Floyd worshipers received an out-of-jail-free card. We should highlight the looters’ fires and the resulting environmental damage. Then, we will see some true justice (dream on). Constitutional due process is now “gone with the wind.” Some environmental zealots refuse to see the unintended consequences. They are people-haters due to their extreme, inhuman devotion to the planet. Some environmentalists may take this paper’s words out of context. But, of course, a sustainable environment is possible through reasoned measures.

I hope those who want a clean environment will see that this movement has gone too far. Considering Hanousek’s plight, would these same zealots have a different view if a close relative faced the same plight?

Conclusion

The United States vs. Edward Hanousek case underscores a troubling trend in environmental justice and legal accountability. Hanousek, a manager at the Pacific & Arctic Railway and Navigation Company, faced criminal charges and imprisonment for an environmental incident he neither caused nor was present for. This incident, where a contractor’s error led to an oil spill in Alaska’s Skagway River, resulted in Hanousek being held accountable due to his managerial position despite being off duty.

This case highlights the broader issue of prosecuting managers for their companies’ actions, even when employees act against instructions. Eliminating the intent requirement in public welfare laws, such as those dealing with healthcare, antitrust, and the environment, has led to severe consequences for individuals like Hanousek. These laws, intended to protect the public from pollution, often blur the lines between civil liability and criminal felonies, resulting in disproportionate penalties. Hanousek’s defense argued that penalizing simple negligence under public welfare laws violates due process. However, the court upheld the stringent application of these laws, emphasizing their role in safeguarding the public. This decision reflects a shift towards prioritizing environmental protection over individual rights, raising questions about the fairness and balance of current legislation.

The silence from civil libertarians and equality advocates on this issue is concerning. It suggests a troubling acceptance of extreme measures in the name of environmental protection, sometimes at the expense of due process and fundamental human rights. This case calls for a reassessment of how public welfare laws are applied and a balanced approach that considers environmental sustainability and individual rights.

In conclusion, the Hanousek case is a cautionary tale about the potential overreach of environmental justice initiatives. It urges us to reflect on whether current practices align with principles of fairness and justice. As we strive for a cleaner environment, we must ensure that our legal frameworks do not trample on the rights of individuals, advocating instead for reasoned and balanced measures that protect both the planet and its people.

Bonus No. 1: White Pass and Yukon Route History

The White Pass and Yukon Route (WP&YR) is a historic narrow-gauge railroad. Its three-foot gage track links Skagway, Alaska, to Whitehorse, Yukon, Canada. Built during the Klondike Gold Rush of the late 1890s, its goal was to aid prospectors and their supplies by providing a safer route.

Construction began on May 27, 1898. British financiers and American engineers led the effort. The tough terrain, steep slopes, and harsh weather made the job difficult. Yet, the workforce, which included many immigrants, finished the 20-mile track to White Pass Summit within a year.

By July 29, 1900, the full 110-mile line to Whitehorse was complete. The WP&YR quickly became a vital transport route. It replaced the dangerous trails prospectors once used. The railroad was crucial for moving people, supplies, mail, and goods, which boosted economic growth.

After the gold rush, the WP&YR’s traffic declined. It continued to operate, serving industries such as mining. The Alaska Highway’s construction during World War II lessened its importance for freight. In 1982, due to falling metal prices and mine closures, the WP&YR shut down.

In 1988, the WP&YR reopened as a heritage railway for tourists. They can enjoy the history of the Gold Rush with scenic trips through the Coastal Mountains. Today, the WP&YR boasts its world-renowned passenger train as its prime business. It showcases the area’s history and beauty.

The WP&YR is an International Historic Civil Engineering Landmark. This recognition honors its engineering feats and place in history. It is a tribute to its builders’ and workers’ hard work and dedication. The railroad offers a glimpse into the early transportation challenges in North America’s northern regions.

Bonus No. 2: Frederick R. Smith at WP&YR

Pictures of my WP&YR trip on June 2, 2010.

Parting Shot

Suggestion for business owners: hire only DEI (Didn’t Earn It) candidates for posts targeted by the Make America Communist Altogether (MACA) mob. That way, Soros-funded DAs and WOKE federal prosecutors will look the other way when WP&YR-like incidents occur. 📕

Sources

The White Pass: Gateway to the Klondike ~ Roy Minter, 394 pages, University of Alaska Press, February 1987

I warmly encourage you to consider becoming a paid subscriber if you have the means. Tips are appreciated, too. Regardless of your choice, your support is deeply appreciated. From the bottom of my heart, thank you for your invaluable support!

Great post. The alphabet agencies work on the premise that you are guilty till you prove yourself innocent, with no regard for Constitutional rights.

In May of 1861, 9 year old John Lincoln "Johnny" Clem ran away from his home in Newark, Ohio, to join the Union Army, but found the Army was not interested in signing on a 9 year old boy when the commander of the 3rd Ohio Regiment told him he "wasn't enlisting infants," and turned him down. Clem tried the 22nd Michigan Regiment next, and its commander told him the same. Determined, Clem tagged after the regiment, acted out the role of a drummer boy, and was allowed to remain. Though still not regularly enrolled, he performed camp duties and received a soldier's pay of $13 a month, a sum collected and donated by the regiment's officers.

The next April, at Shiloh, Clem's drum was smashed by an artillery round and he became a minor news item as "Johnny Shiloh, The Smallest Drummer". A year later, at the Battle Of Chickamauga, he rode an artillery caisson to the front and wielded a musket trimmed to his size. In one of the Union retreats a Confederate officer ran after the cannon Clem rode with, and yelled, "Surrender you damned little Yankee!" Johnny shot him dead. This pluck won for Clem national attention and the name "Drummer Boy of Chickamauga."

Clem stayed with the Army through the war, served as a courier, and was wounded twice. Between Shiloh and Chickamauga he was regularly enrolled in the service, began receiving his own pay, and was soon-after promoted to the rank of Sergeant. He was only 12 years old. After the Civil War he tried to enter West Point but was turned down because of his slim education. A personal appeal to President Ulysses S. Grant, his commanding general at Shiloh, won him a 2nd Lieutenant's appointment in the Regular Army on 18 December 1871, and in 1903 he attained the rank of Colonel and served as Assistant Quartermaster General. He retired from the Army as a Major General in 1916, having served an astounding 55 years.

General Clem died in San Antonio, Texas on 13 May 1937, exactly 3 months shy of his 86th birthday, and is buried at Arlington National Cemetery.

The Remarkable Journey of Johnny Clem: From Drummer Boy to Major General

https://www.wethekids.us/the-remarkable-journey-of-johnny-clem-from-drummer-boy-to-major-general/

https://scontent.fjbr1-1.fna.fbcdn.net/v/t39.30808-6/442439634_122151711134165951_1341351085445262278_n.jpg?_nc_cat=100&ccb=1-7&_nc_sid=5f2048&_nc_ohc=XuyRYVSxKOAQ7kNvgHM_bCR&_nc_ht=scontent.fjbr1-1.fna&oh=00_AYC5SKtZl-nYin_xxdGqDq9QuAp19r-S5DCtJ448_CrkAA&oe=665170D4