Volitaire, Robespierre and Religion of Reason

The principal worldview and driving force of the French Revolution, the Reign of Terror, was “pure” reason. The philosophes looked to destroy anything that was not in line with pure reason.

Francois Marie Arouet (pen name Voltaire), 1694 – 1778, was one of France’s most celebrated and acclaimed writers and philosophers. As a follower of the “Enlightenment,” Voltaire was also known as a “philosophe.” Voltaire had an influence on those fueling the French Revolution, although he did not live to see its outbreak in 1789. He was France’s prominent Enlightenment philosopher, writer, and social critic. He had wit and sharp intellect. Voltaire advocated for individual liberties including freedom of speech, religion, and expression. Voltaire's writings and ideas contributed to the intellectual climate of the French Revolution. Some of the elements in which he influenced the Revolution include:

A critic of the absolute monarchy and the aristocracy in France. He condemned the abuses of power, corruption, and privileges enjoyed by the nobility. He advocated for a more egalitarian society.

Believed in the importance of religious tolerance.

Critical of religious intolerance and persecution. He advocated for the separation of church and state and the right to freedom of religion.

Defended the right to freedom of expression. Believed that an enlightened society should encourage open debate and exchanging ideas.

Ideas and writings inspired other prominent Enlightenment thinkers. Some of the permanent philosophers included Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Montesquieu, and Diderot. They further contributed to the intellectual groundwork for the French Revolution.

Literary works, including essays, plays, and letters, reached a wide audience. They contributed to the dissemination of Enlightenment ideas to the public.

Voltaire’s influence on the French Revolution was undeniable. But the revolution was a complex and multifaceted event. Various social, economic, and political factors led to the Revolution. Thus, it is important to note that no individual idea or person caused the Revolution. The Revolution happened because many groups had complaints and dreams, not because of one person's influence. They sought political and social change. Liberty, equality, and fraternity became central to the French Revolution's goals. Taking these ideals to the extreme caused mass psychoses. That resulted in the murder of thousands of people, most innocent. Even Thomas Jefferson found the French Revolution to inspire change but later denounced its accesses.

Voltaire's ideas had a significant influence on Thomas Jefferson. He was an avid reader and a key figure of the American Enlightenment. Jefferson found delight in the ideas of the European Enlightenment, of which Voltaire was a prominent figure.

Voltaire represented Enlightenment ideas and affected Western thinking. His conceptual framework contributed to the advancement of European philosophy. He viewed philosophers as engaged citizens and advocates, valuing abstract reasoning when pertinent. He introduced an idea that changed how we test philosophy's value in society. This notion held considerable sway. Karl Marx thought philosophy should change the world, not explain it. This was unlike Voltaire's view. Marx agreed with Voltaire and the French revolutionaries, connecting himself to their beliefs.

The legacy of Voltaire became inseparable from that of Marx within this tradition. The movement embraced Voltaire as a foundational figure, a heroic progenitor. In 1791, the new government created the Pantheon of Great Men of France to honor extraordinary people. After Voltaire's death, they buried him inside the important walls of the church. This represented a connection between his ideas and the revolutionaries. This act honored the connection between Voltaire's ideas and the goals of those seeking change.

In 1778, a decade before the Reign of Terror during the French Revolution, Voltaire’s final play, “Irene,” opened in Paris. Once vanquished from France, Voltaire spent his last days attending a play performance. The crowds greeted him with feverish excitement. Voltaire is still seen as a model for people who use critical thinking to challenge political norms.

College professors, students, and the intellectual elite admire Voltaire and his fellow philosophes. Many of our esteemed elite philosophers downplay the terrors of the French Revolution, a product of the Enlightenment. These elites claim that the “anti-philosophies” of yesteryear are like the modern “dark right-wing of today.” That prevents “progress.” Today conservatives are “rabid,” “radical,” “extreme,” “fundamentalist,” “right-wing Christian,” “xenophobic,” etc. For more, read the book “Enemies of the Enlightenment: The French Counter-Enlightenment and the making of Modernity” by Darrin M. McMahon.

The anti-philosophes or “Counter-Enlightenment” was a diverse group of people. They worked to expose the dangers of unfettered Enlightenment during the time of well-known writers such as Voltaire. Few writings exist about anti-philosophes, but it is fashionable to write about their “excesses.” At the same time, they downplay the acts committed by many of the movers and shakers of the French Revolution, such as Robespierre.1 Furthermore, modern pro-enlightenment philosophers sweep Jacobin’s role under the rug. A serious study shows that the members of the Jacobin Club were totalitarians. They had an infatuation with conspiracy theories.

The Jacobin Club met at the former monastery of St. Jacques (Latin; Jacobus; the French name of the Dominican Order). They were the members of the French National Assembly who allowed the mob to influence voting. The Jacobins came under the influence of Robespierre, the real focus of the radicals and the Reign of Terror. The Jacobins first admitted the public to their meetings on October 14, 1791.

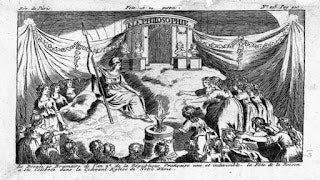

The principal worldview and driving force of the French Revolution, the Reign of Terror, was “pure” Reason. The philosophes looked to destroy anything not in line with pure Reason. Religion, of all types, was their main enemy. They believed that sin was a myth and thought the Catholic Church was the main culprit. While they celebrated “tolerance,” they despised religion. In 1789 those who embraced philosophes nationalized all church property. Then they passed a law that made the clerics state officials. To add insult to injury, the people chose the new state clerics (some were non-believers). Some examples of the “separation of church and state.”

It got worse. The revolutionaries worked to remove Christianity from France. They desecrated altars and destroyed church buildings. The full Reign of Terror surfaced in 1793 with full-scale butchering. That was the result of the new faith, the religion of Reason. In November 1793, Notre Dame Cathedral became the “Temple of Reason” as blood flowed throughout France. The comparison between the American Revolution and the French Revolution is spurious.

The excesses of pure Reason can be problematic for some religious zealots. Can Reason and faith co-exist? The answer is an absolute yes. The American Revolution is an excellent example of how religion and Reason can work together. That also is the difference between the French and American Revolutions.2 Here in the United States, the founding era’s humble faith and common sense shaped our laws. Christians such as Dr. Benjamin Rush collaborated with Enlightenment followers like Thomas Jefferson. Together they developed our founding principles.

For many decades we experienced a resurgence of pure Reason. There is a penchant for non-believers to impose their secular religion in every aspect of our lives. Christians do not wish for a theocracy but must express religious sentiments freely. The secularists force-feed their twisted “religion of Reason” throughout society.

My dear friends, in 2020, we live in a time of a “cancel culture” that erases valuable history. Would you mind praying we do not see a repeat of the French Revolution due to ignorance?

Cogent author and publisher, Frederick R. Smith

Cogent Editor, Sean Tinney

Maximilien François Marie Isidore de Robespierre (1758-94) was a French lawyer and political leader. He became one of the most influential figures of the French Revolution and the principal exponent of the Reign of Terror. Born in Arras and educated in Paris at the College of Louis-le-Grand and the College of Law, Robespierre became a passionate devotee of the social theories of the French philosopher Jean Jacques Rousseau. He was elected a deputy of the Estates-General that convened in May 1789 on the eve of the French Revolution. Subsequently, he served in the National Constituent Assembly, where his earnest and skillful oratory soon commanded attention. In April 1790, he was elected president of the Jacobin Club and became increasingly popular as an enemy of the monarchy and an advocate of democratic reforms. He opposed the more moderate Girondists, the dominant faction in the newly formed Legislative Assembly.

American independence occurred because of the colleges that many of the Founding Fathers attended. The combination of faith and Reason best illustrates the teachings of Rev. Samuel Davies (1721 – 1761). He was the president of the College of New Jersey (Princeton) and taught that Reason and Revelation complemented each other.