Giant Government Gravy Train

This essay shows how federal money landing onto specific railroad projects can be wasteful at best or corrupt at worst.

Foreword

This essay shows how federal money landing onto specific railroad projects can be wasteful at best or corrupt at worst.

Background

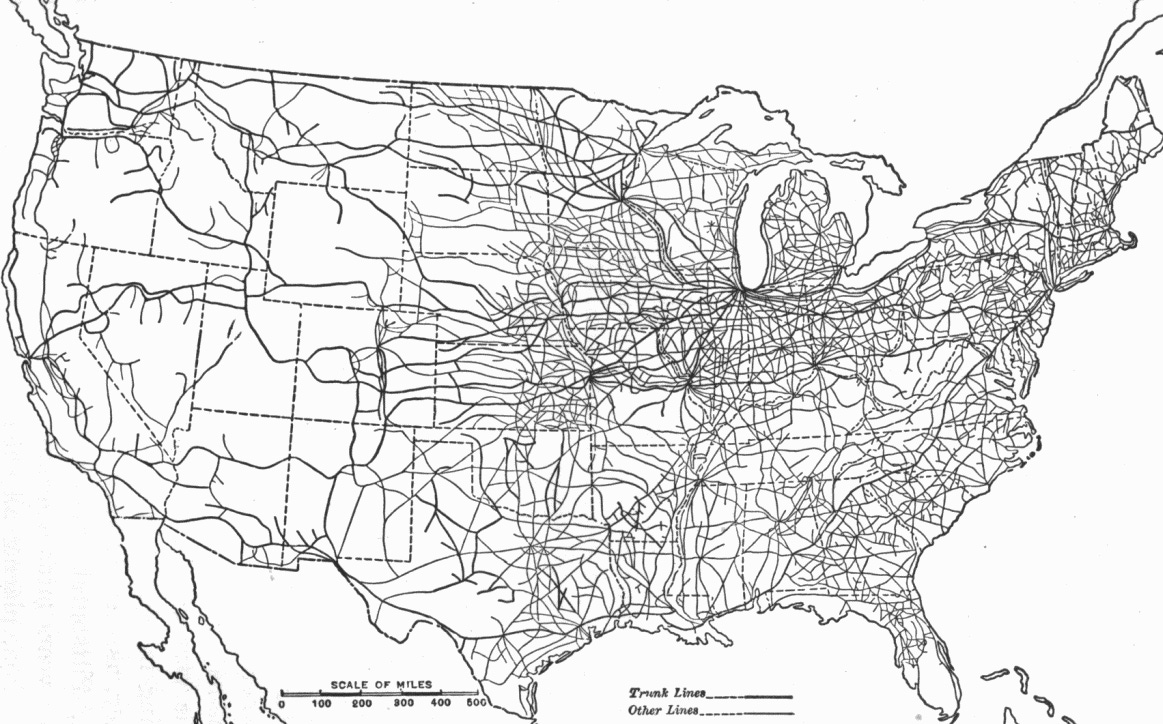

The common carrier1 railroads in the United States move 40 percent of the intercity freight traffic. There are seven significant railroads and about 623 smaller “short line” and “regional” freight railroads. Rail freight is a well-integrated 56.5-inch standard gauge system extending into Canada and Mexico.

Amtrak, a Federally owned Corporation, provides nationwide passenger train services. For most routes, it operates over the freight railroads. Amtrak owns the Northeast Corridor (Washington, DC - Boston, MA) and Michigan Line (Porter - Kalamazoo). Also, please see Frederick R. Smith Speaks “Green New Deal Pop-Up Posters and More!” for a hilarious satirical look at the Northeast Corridor.

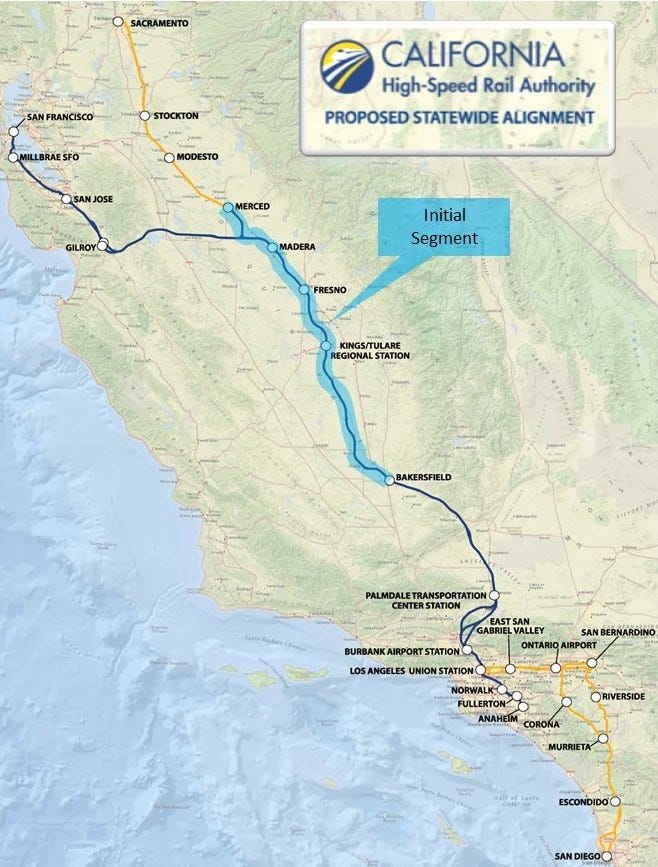

Brightline in Florida (Miami - Orlando) is a new privately-owned and financed passenger line. Local and state agencies own 33 commuter railroads. The under-construction California High-Speed Rail system promises speeds up to 220 miles per hour in some places. Under the Analysis Section, please see “California ‘High Speed’ Leviathan.”

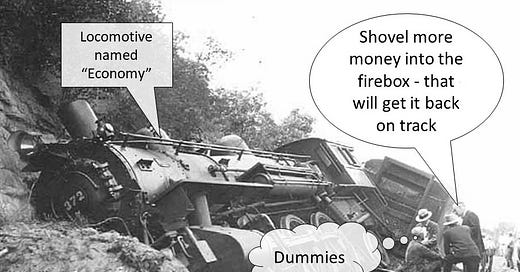

The earliest railroad construction started in the 1820s, in New England and the Mid-Atlantic region. On May 8, 1869, the builders drove the Golden Spike in Promontory, UT. That historically celebrated completion of the transcontinental. It connected California with the rest of the national network in Iowa. Railroads continued to expand throughout the rest of the 1800s, reaching every corner of the nation. Today, they move mega imports and some exports using containers and haul shipments of coal and oil. Also please see Frederick R. Smith Speaks Russia, Russia, Russia & Ride the Rails.

The US network went from 254,251 route miles in 1916 to the current 140,000 miles. With the system declining in the 1970s, many states purchased unprofitable lines. That “railbanking” effort proved to be an invaluable infrastructure investment. Today, private railroads operate many of these lines under lease agreements with the states.

Railroads still play a significant role in freight shipping despite the route decline. They carried 750 billion ton-miles by 1975 to an all-time high of 1.7 trillion ton-miles in 2018. This increase, despite fewer tracks, is possible due to innovations. That includes heavier and longer trains, labor reduction, energy efficiencies, and technologies. These items are not without controversial issues related to safety.

Publicly-traded corporations own the vast majority of the rail lines. While they are not government entities, many railroads use state and federal grants for capital projects. Short-line and regional railroads take advantage of federal and state funding programs. Under the Analysis Section, please see “Bountiful Bridge.”

While few people interact with trains, everybody sees railroad tracks as they travel by highway. Motorists encounter railroads as they drive over at grade highway-rail crossings. In the United States, there are about 120,000 public grade crossings. As viewed by motorists from a safety perspective, there are two types of crossings.

Passive - advance signs and crossbucks at the crossing. Generally, motorists yield to trains they see approaching trains hear engine horns

Active - crossings equipped with automatically activated flashing lights or gates and flashing lights to warn motorists of approaching trains

The Federal Highway Administration Section 130 Railroad-Highway Grade Crossing Program provides federal funds to mitigate existing at-grade highway-rail crossing hazards. This program is funded with 90 percent federal dollars and a 10 percent state match. Annually more than $240 million federal dollars go to states to install new active warning devices, upgrade existing devices, and improve grade crossing surfaces.

Projects of Interest

Your Author chose five contemporary railroad engineering projects to illustrate the Giant Government Gravy Train (best and worst) in action. As a backdrop, the BNSF Railway project shows how 100 percent private investment works best.

Bountiful Bridge

This project is an example of a state/railroad partnership. It consists of new bridge construction on the regional carrier Reading Blue Mountian and Northern Railroad (RBMN). In 2019, RBMN built a new bridge over the Lehigh River near Jim Thorpe, PA. Costing $14 million, the state of Pennsylvania provided $10 million. RBMN provided the remaining $4 million.

It is unknown if federal money came through the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania for this project. This bridge forms a new connection between two separate rail lines that enables trains to operate directly between Reading, PA, and Scranton, PA. This effort seems to be the “safe and effective” of the four government-funded projects outlined in this essay.

California “High Speed” Leviathan

California High-Speed Rail promised to connect Los Angeles and San Francisco. The initial plan called for a $33 billion price tag. Construction started in 2012, three years late. So far, this Leviathan has spawned $98 billion (and counting) in spending. The first segment of the line will only span about 185 miles between Merced and Bakersfield. That initial section might be operational in 2029.

So far, as reported by the Authority, it has secured approximately one-third of the funds needed to complete the current estimated cost of the system:

2008 - Californians voted to build electrified high-speed rail by approving Proposition 1A, which provided $9.95 billion for high-speed rail planning and construction

2009 - the Authority received $2.5 billion in federal funds through the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009

2010 - Congress appropriated $929 million in additional federal funding from Fiscal Year (FY10) Transportation, Housing and Urban Development funds (!)

2014 - California Legislature appropriated 25 percent of the annual proceeds from the Cap-and-Trade Program

2017 - California Legislature extended the Cap-and-Trade Program to support this project through 2030

Despite the public relations attempt to make this project the poster child of the Green New Deal, a Leviathan lurks in the background. Once in a while, we get to see the monster behind the curtain with California Democrats appearing to get cold feet. It is a financial sinkhole, but governor Newsom charges on rather than admitting this colossal mistake. The politicians and their labor union partners pulled off one of the biggest magic tricks in history. The Central Valley now has farmlands carved up and littered with construction debris to make way for this pipe-dream. In a Twilight Zone-like episode, California “leadership” neither want to move forward nor admit defeat.

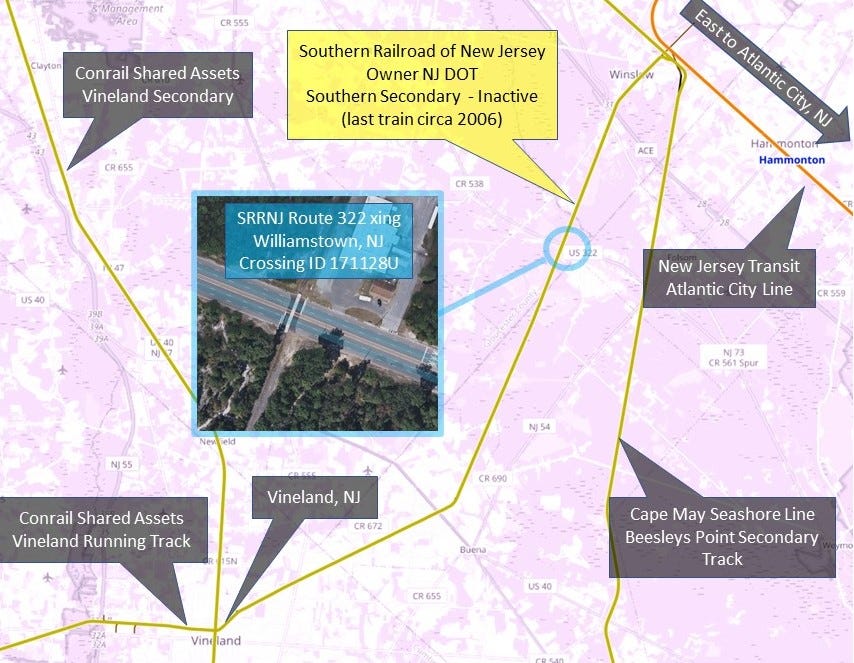

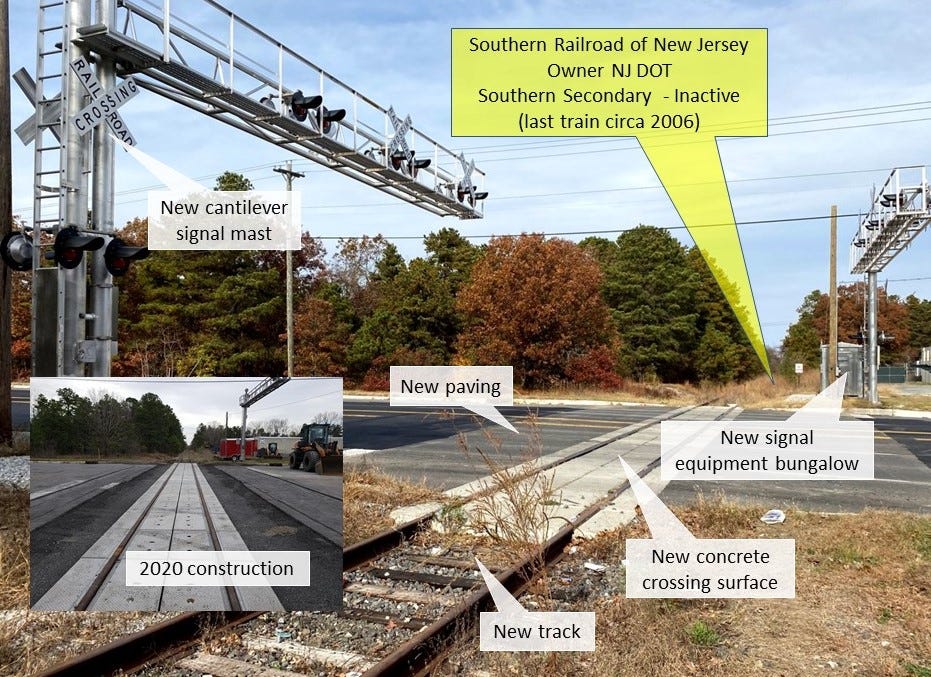

Clueless Crossing

Williamstown, NJ, is located between Philadelphia, PA, and Atlantic City, NJ. In this area of “South Jersey” known as the “Pine Barrens,” the major highway Route 322 has four lanes, and it intersects with a railroad line at grade. In April 2020, NJ DOT detoured traffic for ten days around the site to rebuild this crossing and associated warning devices.

As detailed in the above illustration, no trains operate over this rail line. Passage by rail is now impossible due to trees growing in the track, rotten crossties, and broken rails. This line was never “formally abandoned” through Surface Transportation Board proceedings. Therefore, planners treat it as an “active” rail line for grant purposes. That provided the excuse to not pave over this crossing for minimal dollars. New Jersey Department of Transportation spent over $400,000.00 to upgrade the track, highway pavement, track circuits, and active warning devices.

With 90 percent Federal and 10 percent state funding, local contractors and material suppliers made money constructing a crossing that has seen no trains in 14 years. No plans exist anticipating the use of this rail line in the near and distant future.

Forty-Seven Million Dollar Mile - Amtrak

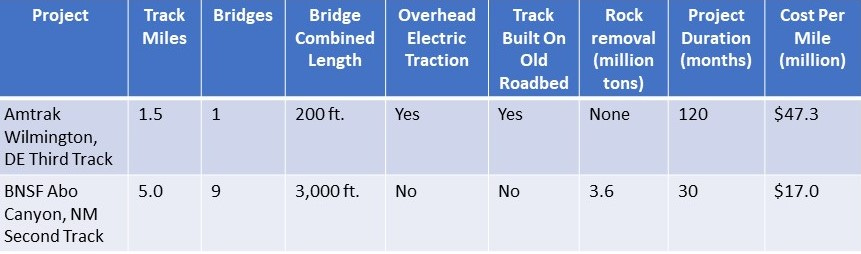

In December 2021, Amtrak and the Delaware Department of Transportation celebrated a project completion. It centered around the $71.2 million Amtrak Northeast Corridor (NEC) “Third Track” effort. Located In Wilmington, DE, this project provided capacity improvement for the NEC. It entailed the construction of a 1.5-mile mainline track. Additional project elements included:

Turnouts (switches) connecting the new track

Bridge over a creek

Overhead electric traction wire (catenary)

Wayside signal and communication infrastructure

In 2011, this project began as a “shared benefit investment” between the Delaware Transit Corporation (DTC) and Amtrak. DTC contracts with Southeastern Pennsylvania Transportation Authority (SEPTA) for commuter rail service. Before completing the work, the project area was a “choke point” of two tracks. SEPTA and Amtrak trains experienced delays due to the restrictive service capacity limits. Funding came from the following entities (all pass-thru Federal monies):

Amtrak (Federal entity)

Grant issued to Delaware Transit Corporation from the Federal Railroad Administration

Federal Transit Administration

Federal Highway Administration (a puzzlement why highway funds go to a 100% railroad project)

This project of $71.2 million averages a cost of $47.3 million per mile. Of note, this work occurred on an old roadbed. Thus, no rock excavations or property acquisition occurred. The final price tag is a stunning example of the obscene cost of government-owned and funded projects. Still, the movers and shakers “celebrated” the project’s completion. For sure, the contractor (and its employees) and railroad union employees mourned the end of this Gravy Train. Not to worry, the prime rib gravy train is in the works with the passage of the 2021 Infrastructure Bill.

Seventeen Million Dollar Mile - BNSF

BNSF has been working to double and triple-track its entire Transcontinental line. It spans 2,200 between the west coast and Chicago. This line had a combined 512 miles of single-track. In 1992 BNSF set a goal to double-track these single-track segments. This effort exemplifies the efficiency of private investment and projects.

One of the most significant improvements occurred at Abo Canyon, about 25 miles east of Belen, NM. It was a four-mile-long single-track chokepoint. In March 2011, BNSF completed a 30-month $85 million effort to build a second track in the Canyon. This required movement of about 3.6 million tons of rock, laying five miles of new track, and building nine new bridges with a combined length of about 3,000 feet.

The constructed track is on a “split grade,” meaning a separate alignment and right of way. BNSF purchased land beyond the original single-track property to make this happen. This arrangement enabled the BNSF to reduce grades along the new track. That improved operating efficiencies and fuel savings.

As a result of this state-of-the-art engineering effort, train capacity went from about 80 freight trains a day to more than 130. Costing $85.02 million, it averages to $17.0 million per mile.

Analysis

For the Bountiful Bridge, Fred Smith gives a thumbs-up at best or a horizontal thumb at worst. California “High Speed,” the Giant’s Leviathan, speaks for itself. “Clueless Crossing” stands alone as the prima facia example of how to throw money out the window at the tune of $400,000.00.

The comparison of Amtrak ($47.3 million per mile) versus BNSF ($17.0 million per mile) shows a stark reality. Even with inflation counted in, it is still a money hole. That shows the difference between a clumsy federal effort and an efficient private sector project. Even with all the federal and state rules and regulations, BNSF is a shining example of good old USA ingenuity.

By accounting for inflation, the Amtrak project, in today’s dollars, makes it about 33 percent higher per mile than the BNSF effort. And, Amtrak took four times longer to complete their task. That analysis shows the disparity between government and private construction projects—the prime takeaway: money. Tax revenue and fiat cash provided the Amtrak and Clueless Crossing project funding. That means we all pay for countless projects like this with taxes and a hidden tab called inflation (the result of fiat money). Also, see Frederick R. Smith Speaks Creature from Jekyll Island.

Afterword

In November 2021, Congress passed and President Biden signed the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act. This $1.2 trillion legislation includes $66 billion for passenger and freight rail. Given the information presented in this essay, it will be a wonder to see if these funds go forward in a “safe and effective” manner.

Sources

Trains Magazine, February 2022

Fred Smith’s railroad library

Fred Smith on-site observations

Facebook group: Railroads of Southern New Jersey

Cogent author and publisher, Frederick R. Smith

“Common carrier” refers to any entity which serves the general public transporting people or goods. This essay does not address local rail transit lines and private railways such as industrial and tourist/historical trains operating on non-common carrier tracks.

At least California's nonexistent high-speed rail loves diversity https://www.washingtonexaminer.com/opinion/at-least-californias-nonexistent-high-speed-rail-loves-diversity

Los Angeles will receive a $893 million federal grant to fund a new light rail line after years of lobbying from officials. At 6.7 miles, the rail line will run through Panorama City, Arleta, and Pacoima to connect a number of neighborhoods in the San Fernando Valley. It is estimated to cost $3.6 billion, and the funding is the first grant under the Federal Transit Administration's Expedited Project Delivery (EPD) Pilot Program. https://www.transit.dot.gov/funding/grants/grant-programs/expedited-project-delivery-pilot-program-section-3005b