First Flight 1793 and the Finest Part 1 - Introduction

Before the Wright brother’s experiments with gliders and successful machine-powered airplane flight in 1903, President George Washington witnessed the first flight in the United States.

It does not seem to me a good reason to decline prosecuting a new experiment which apparently increases the power of man over matter until we can see to what use that power may be applied. When we have learned to manage it, we may hope some time or other to find uses for it, as men have done for magnetism and electricity, of which the first experiments were mere matters of amusement.

Benjamin Franklin

Preface

Please note that all parts of this extensive essay are in my Substack as a published product. Readers who receive email notifications will only get this installment (Part 1) delivered to their inbox. Please read all the parts at your leisure online (hyper-linked below). Enjoy!

Prologue

It is a great honor to present this essay about important but little-known figures from the early history of the United States: General Stephen Moylan and balloonist Jean-Pierre-François Blanchard. The interaction and reactions of some more well-known figures, such as Benjamin Franklin, John Adams, and Thomas Jefferson, supply an engaging story.

My friend Stephen R Moylan of the same family tree as General Moylan and his connection to the Blanchard family provides intrigue. My fondness for early American history and first-hand knowledge gave me a unique writing opportunity. Enjoy the story of how the modern-day ballooning efforts of Stephen R. Moylan give us a window back to 1793. It is a remarkable privilege to present a first-time detailed historical essay about the first manned flight in America and its modern-day legacy.

Part 1 - Introduction

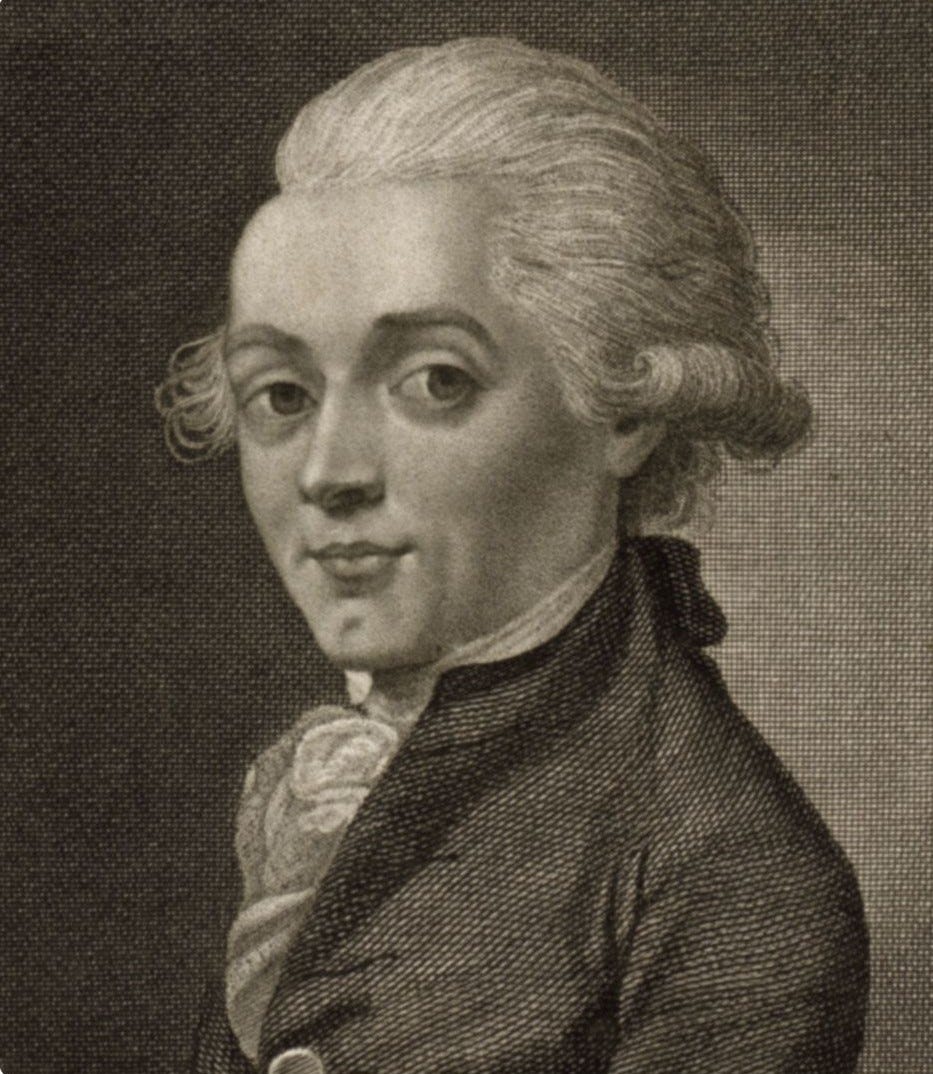

Before the Wright brother’s experiments with gliders and successful machine-powered airplane flight in 1903, President George Washington witnessed the first successful flight in the United States. On January 9, 1793, Jean-Pierre-François Blanchard operated his untethered balloon.1 He ascended from the Walnut Street Prison yard in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, and landed in Deptford, Gloucester County, New Jersey.

Jean-Pierre-François Blanchard (1753-1809)2 was a French balloonist, along with American physician John Jeffries, who made the first aerial crossing of the English Channel. Blanchard and his first wife Victorie LeBrun had three daughters and one son, who died at 16. Blanchard married his second wife, 18-year-old Marie-Madeleine-Sophie Armant, in 1798. She also became an aeronaut.

In addition to the first flight in North America, Blanchard was also the first to make balloon flights in England, Germany, Belgium, and Poland. During the 1770s, He worked on designing heavier-than-air flying machines. One of his devices used a theory of rowing in the air currents with oars and tiller. Impressed by the hydrogen gas balloon ascensions by Jacques Charles and the demonstrations of the hot-air balloon operation by Joseph-Michel and Jacques-Étienne Montgolfier (Montgolfier brothers) in 1783, Blanchard took up ballooning.

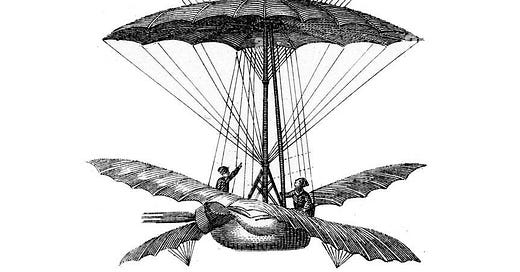

Previously in 1781, Blanchard invented and constructed his mechanical flying machine based on the “ornithopter” principle.3 It had four great wings operated by hand and foot levers. While mechanically successful, the “Vaisseau Volant” lacked the power to gain flight. Other inventors pursued the dream of flying.

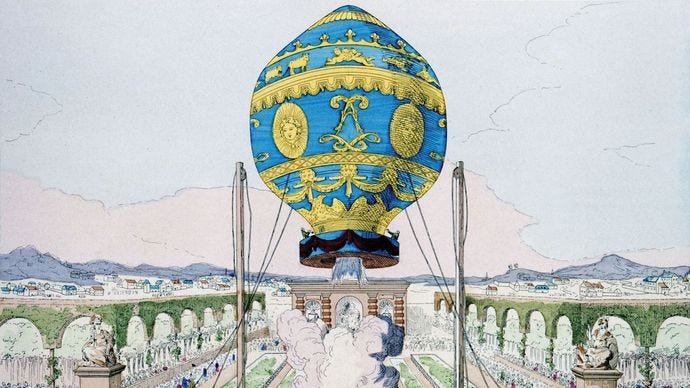

In 1872, the Montgolfier brothers discovered that heated air, when collected inside a large lightweight paper or fabric bag, caused the device to rise. They made the first public demonstration of an unmanned flight at Annonay, France, on June 4, 1783. It was an eight-minute-long experiment in which their apparatus of sackcloth and three thin layers of paper. So-called “rarified” air generated by burning wool and straw provided the lift. The balloon rose to 3,000 feet and floated for 1.5 miles before crashing in flames. The next Montgolfier test was on September 11 from the grounds of la Folie Titon garden in Paris. There was some concern about the effects of flight into the upper atmosphere on living creatures. The king proposed to launch two convicted criminals, but it is most likely that the inventors decided to send a sheep, a duck, and a rooster aloft first.

After the pioneering Montgolfier brothers’ success, Jacques Charles joined forces with two local craftsmen, brothers Anne-Jean and Marie-Noel Robert, to produce a superior balloon. The balloon they constructed (called ‘The Globe’) was 12 feet in diameter, made of silk with an impermeable rubberized coating to contain hydrogen (lifting gas). The unmanned balloon ascended from the Champ de Mars on August 27, 1783, and rose 3,000 feet before falling to the ground 15 miles away. Benjamin Franklin, who was present, wrote a letter dated August 30, 1783, about the event, addressed to Sir Joseph Banks, President of the Royal Society of London.

Montgolfier brothers completed their first successful flight with a hot-air balloon on September 19, 1783. The event occurred with King Louis XVI and Queen Marie Antoinette witnessing it at the Royal Court. The Montgolfier balloon ascended carrying a sheep, rooster, and a duck. It rose to 1,500 feet and traveled two miles in eight minutes. On November 21, 1783, the first untethered manned flight occurred. Jean-François Pilâtre de Rozier and François Laurent, marquis d'Arlandes, ascended over Paris on board a Montgolfier balloon. The balloon sailed over Paris for 5.5 miles in about 25 minutes.

On December 1, 1783, professor Jacques Charles and the Robert brothers launched a new, manned hydrogen balloon from the Jardin des Tuileries in Paris amid vast crowds and excitement. The Robert brothers accompanied Jacques Charles as co-pilot of the 380-cubic-meter hydrogen-filled balloon. They ascended to a height of about 1,800 feet and landed at sunset in Nesles-la-Vallée after a flight of 125 minutes, covering 22 miles.

In 1783, three prominent Americans, Benjamin Franklin, John Adams, and John Jay, were in Paris negotiating, on behalf of the United States, finalizing the peace treaty to end the Revolutionary War. They were witnesses to the balloon flights and a source of information to Americans. Benjamin Franklin wrote to his network of scientific correspondents about the balloon developments as early as July of that year. In a letter to Congressman Robert Livingston, John Jay predicted that “travelers may hereafter literally pass from country to country on the wings of the wind.”

Blanchard made his first successful balloon flight in Paris on March 2, 1784, in a hydrogen gas balloon launched from the Champ de Mars in Paris. Blanchard’s third aerial voyage, from Rouen in Normandy, on July 18, 1784. Accompanied by M. Boby, in which they traversed a space of forty-five miles in two hours and 15 minutes.

On January 7, 1785, Blanchard and John Jeffries ascended over Dover, England. Jeffries covered the 700-pound expense of the flight in exchange for his being allowed to accompany Blanchard. Not wanting to share in the glory of the voyage, Blanchard reportedly tried to find ways to exclude Jeffries from the flight. A few days before the flight, Blanchard had a tailor sew weights into his vest. While wearing the vest, he planned to declare the balloon was overweight, and Jeffries would have to remain behind for the flight to have any chance of success. Jeffries discovered the ruse and demanded his rightful place on the flight.

During the flight, the two aviators were compelled to toss all cargo overboard except the package of the first international air-mail, delivered successfully upon their safe landing in the Felmores Forest, France. Blanchard unsuccessfully tried using sails to add maneuverability and facilitate propulsion in balloons.

A few days later, Blanchard and Jeffries met with Louis XVI and then had dinner with Benjamin Franklin at Passy, France. These two, and Franklin’s grandson Temple, were the recipients of the first air-mail letters sent from London in the balloon. Franklin wrote to James Bowdoin in Boston that:

I sent to you some weeks since, by Mr. Gerry, Dr. Jeffries’ account of his aerial voyage from England to France, which I received from him just before I left that country. My acquaintance with Dr. Jeffries began by his bringing me a letter in France, the first through the air, from England.

On orders to replace John Jay, Thomas Jefferson arrived in Paris in August 1784 to join up with Adams and Franklin for trade negotiations with various nations. On September 19, 1784, the Robert brothers and M. Collin-Hullin flew a Montgolfier “rarified” (hot air) balloon for 6 hours 40 minutes, covering 150 miles from Paris to Beuvry near Béthune. The Adams family (John, Abigail, John Quincy, and Nabby), Jefferson, and “eight or ten thousand” others attended the celebrated spectacle at the Jardin des Tuileries. “Came home and found Mr. Jefferson again,” Nabby would record another day. “He is an agreeable man.” Here is that scene from the HBO documentary “John Adams.”4

At 40, Blanchard traveled to the United States on board the ship Ceres with his son Julien Joseph.5 He departed from Hamburg, Germany, on September 30, 1792, and arrived in Philadelphia on December 9th. Oeller’s Hotel lodged the duo from France and their folded balloon and “boat” (aerostatic apparatus), ready to receive the press.6

It was a provocative time with the French Revolution raging and the birth of the Republic. In Philadelphia, Blanchard found intense partisan interest in “Liberte, Egalite, and Fraternite.” Just 12 days after Blanchard’s Philadelphia flight, King Louis XVI fell under the blade of a guillotine. Previously in France, Blanchard faced imprisonment because of his political interests, but his aeronautic skills earned him the right to be a pensioner.

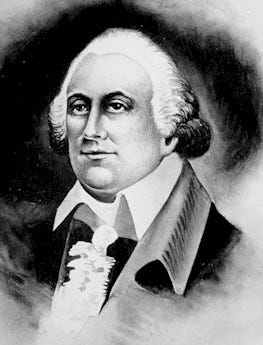

General Stephen Moylan

In 1793, Philadelphia was the capital of the United States and Pennsylvania. City, county, state, and federal government seats were in one row of buildings. Many of the structures that Blanchard saw in 1793 still exist today. The essential facilities include Independence Hall and the Supreme Court Building, with the American Philosophical Building behind it. Many churches from the era remain, as well as the home of General Stephen Moylan. Blanchard, the “Celebrated Balloonist,” lived in the United States for a year at 9 North 8th Street, Philadelphia.

Stephen Moylan is notable as a patriot officer under George Washington. He served the entire Revolutionary War as a Colonel and got elevated to General after the conflict. Today, Stephen R Moylan, a descendant of the same Moylan family as General Moylan, continues the ballooning legacy. As detailed later, a chance encounter and later friendship between Stephen R. Moylan and Blanchard family descendants adds to the intrigue. The 5th section of this essay, “First and Finest,” details the ongoing ballooning efforts by my close friend Stephen R. Moylan in honor of President George Washington, Jean-Pierre-François Blanchard, and General Stephen Moylan.

Stephen Moylan (1737-1811) was an Irish American patriot leader during the Revolutionary War. In 1734 he entered life in Cork, Ireland, when Catholics still lived under penal law with severe restrictions and penalties. Moylan, the son of an ambitious Cork merchant, belonged to a strong Catholic family. One uncle became an order priest in the Jesuits. Of Moylan’s eight siblings, his brother Francis was a secular (diocesan) priest after studies at Paris and Toulouse. With consecration as bishop of Kerry in 1774, Francis transferred to Cork in 1786. Two sisters became Ursuline nuns. Like his brother Francis, Stephen traveled from Ireland to Paris, France, for education.

Following his schooling in Paris, Moylan went to Lisbon, Portugal, for more education. He remained in Lisbon to manage a branch of his family’s shipping business. After three years in Lisbon, Moylan moved to Philadelphia (in 1768). There, he established a new branch of his family’s business. Moylan owned the brigantine Richard Penn of 30 tons, built at Philadelphia. In 1769 the brigantine Minerva, 120 tons, was also registered and listed “Stephen Moylan of Philadelphia” as its owner. His far-reaching business connections are evident in the listing of the ship Don Carlos (a British-built vessel of 100 tons). Records show it as owned by Edward Forrest, a British subject residing in Lisbon, John and David Moylan of Cork, Ireland, and Stephen Moylan.

Like the Catholic landowners of Maryland, the Catholic merchants of Philadelphia faced banishment from politics. They were otherwise permitted to flourish. Sophisticated, courteous, knowing the larger world, and speaking three languages, Moylan rose in social circles.

Since 1751, Protestant Scots-Irish and Catholic-Irish merchants in Philadelphia enjoyed friendships. They found common ground at the Hibernia Fire Company, a club organized around a volunteer firefighting company. In 1766 the Protestant elite founded Gloucester Fox Hunting Club. Elected a member in 1770, Moylan enjoyed the company of such prestigious Protestants as the prominent lawyer John Dickinson. Through Dickinson, Moylan expanded his friendship circle to include other prominent Protestants in the city.

As the author of Letters from a Farmer in Pennsylvania (1767—1768), Dickenson opposed British taxation. Moylan also relished fellowship with Robert Morris, soon to earn a place in history as the financier in chief for the Revolution. Moylan also belonged to the Irish Club, established in 1765 by Irish city merchants. It was a more informal group meeting weekly in Burns’ Tavern for backgammon or mercantile gossip, followed by supper and rum.

On March 17, 1771, the Friendly Sons of Saint Patrick assembled with Moylan as founding president on Saint Patrick’s Day. It was an umbrella organization consolidating the membership of a half dozen or more Irish societies. Like all these clubs, the Friendly Sons of Saint Patrick was ecumenical. Minority Catholic merchants such as Moylan, Thomas FitzSimons, and George Meade stood alongside the Protestant Scots-Irish. Moylan’s brother Jasper was a lawyer in Philadelphia. John, a merchant of that city, served as United States clothier-general during the Revolution.

Moylan was among the earliest to enlist in the colonies’ cause and hurried to join the army before the 1775 Boston battle. Moylan held several positions in the Continental Army. Moylan’s roles included Muster-Master General, Secretary, and Aide to General George Washington, 2nd Quartermaster General, Commander of The Fourth Continental Light Dragoons, and Commander of the Cavalry of the Continental Army.

Upon the recommendation of John Dickinson, he ended up in the commissariat department. His face and manner attracted the attention of General Washington, who, in March 1776, appointed him one of his aides-de-camp. With the recommendation of Washington, in June 1776, congress appointed him Quartermaster General. Moylan resigned from that position the following October.

By request of Washington, in January 1777, Moylan raised the 1st Pennsylvania Regiment of Cavalry. Later, that unit became the 5th Continental Dragoons. Commissioned its Colonel on January 5, 1777, Moylan held that assignment for the rest of the war.

Casimir Pulaski’s appointment as cavalry commander on September 21, 1777, resulted in a cooperation problem. Language barriers (Pulaski spoke next to no English) and differences over tactics also contributed to bad feelings. Moylan faced court-martial charges pressed by Pulaski after the Battle of Germantown (Philadelphia) on October 4, 1777. Acquitted of charges, Moylan became temporary commander when Pulaski resigned in March 1778. Meanwhile, Moylan spent the winter of 1777-78 at Valley Forge.

Moylan saw action in 1779 on the Hudson River and Connecticut. In 1780 he accompanied General Anthony Wayne on the expedition to Bull’s Ferry, New Jersey, and later served in the southern campaign. Moylan served until the close of the war and, before his retirement, gained a commission to brigadier general.

In 1792 General Moylan was a Goshen Township, Chester County, Pennsylvania resident on a farm near West Chester. On April 7, 1792, he was appointed Register and Recorder of Chester County to succeed Persifer Frazier, deceased. He held these offices until December 13, 1793, when Colonel John Hannum succeeded him. On March 20, 1793, Colonel Hannum donated the property upon which St. Agnes’s Church, West Chester, is built. General Moylan was one of the lay trustees of the church.7

In May 1793, Governor Thomas Mifflin of Pennsylvania appointed General Moylan “Major-General of the Division composed of Chester and Delaware Counties.” He accepted it at West Chester, May 25, “with more pleasure as it is a further mark of your friendly attention to me,” he wrote the Governor.

In September 1793, President Washington appointed him the Commissioner of Loans for Pennsylvania. General Moylan moved to the northeast corner of Fourth and Walnut of Philadelphia in 1796. Mrs. Payne occupied the house, with James Madison, a Virginia Congress representative, and rented rooms. Madison married Dolly Todd (née Payne), his landlady’s daughter, in 1794. General Moylan, who, as a tenant, made repairs, deducting expenses from rental to which Mr. Madison objected.

While serving as an aide de camp for Washington, Moylan wrote about the “United States of America.” That was six months before the words appeared in the Declaration of Independence. Moylan married Miss Mary Ricketts Van Horne on September 12, 1778, and had two daughters, Elizabeth Catherine and Maria. His two sons died as children. On April 13, 1811, General Moylan passed at 74. General Moylan had no will, with an estate valued at $800.00 administered by his half-brother Jasper Moylan.

Part 2 - “The First Launch,” reviews the details of Blanchard’s observations leading to the launch and the details from the flight as he crossed the Delaware River.

Author and publisher, Frederick R. Smith

In a hoax, James Wilcox, sponsored by Francis Hopkinson and David Rittenhouse, was supposed to have ascended in a contraption of 47 small balloons. He saved himself from ducking in the Schuylkill River by puncturing the balloons one at a time.

On June 23, 1784, Baltimore Lawyer Peter Carnes sent a 13-year-old Edward Warren aloft on a short, tethered flight. Carnes traveled to Philadelphia for the first attempt of a manned untethered flight from the Walnut Street Prison Courtyard. On July 17, 1784, thousands gathered in Potter’s Field to glimpse the balloon as it came over the housetops. While ascending and the height of ten or twelve feet, the carriage struck against a wall of the court. Carnes tumbled to the ground. Then the crude bag-like balloon quickly shot upward until it looked like a barrel-sized object. Many of the spectators did not realize that Carnes was not aboard. High up, the bag caught fire from the onboard wood-burning furnace. Most thought Carnes had perished, but they knew the truth the next day. A similar attempt in 1884 was said to have occurred in New York.

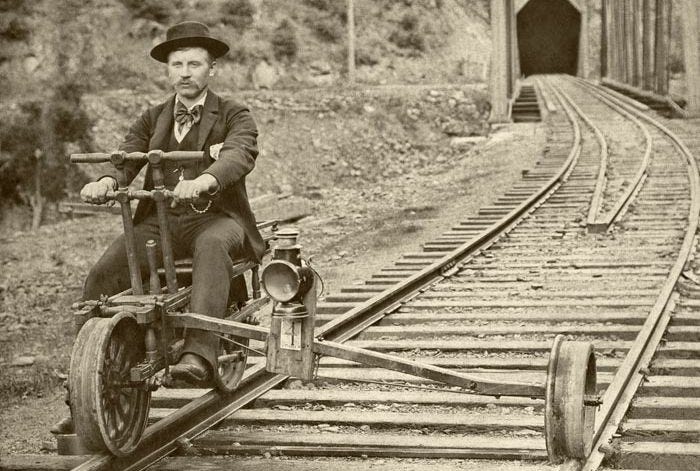

Born in Petit Andelys, Normandy, in 1750, Blanchard was described as “…an unpleasant creature - a petulant little fellow, not many inches over five feet, and physically suited for the vaporish regions.” He was also short-tempered, occasionally rude, and courageous to the bone. In his young teens, Blanchard demonstrated his innovative mind by inventing a more effective rat trap, and an early form of bicycle called a velocipede. Though self-taught, his reputation grew, and he gained work as a professional engineer in Paris, designing a hydraulic pump that could raise water 400 feet.

An ornithopter (from Greek ornis, ornith “bird” and pteron “wing”) is a craft that flies by flapping its wings. The hope was to imitate the flapping-wing flight of birds, bats, and insects. Machines may differ in form but on the same principle as flying animals. Inventors made other more significant manned ornithopters, and some have been successful. Other manned ornithopters are generally either powered by engines or by the pilot.

As a critical observation, in the video, Jefferson says, “the umbilical cord to mother earth is severed for the first time in history.” The historical record indicates earlier untethered flights occurred. Some suggest this scene was from November 21, 1783, thus making Jefferson’s appearance fictitious. However, the account in the book John Adams by David McCullough comports (with the fight date of September 19, 1784).

Launched in France in 1784, the British captured Ceres circa 1800 and sold her as a prize. Once under British ownership, she sailed to the Mediterranean. But, in 1801, she started working the slave trade. She made four voyages as a slave ship, gathering enslaved people in West Africa and delivering them to the West Indies. After the 1807 end of the British slave trade, she became a West Indiaman and East Indiaman. She was last listed in 1822.

To excited young men of Philadelphia wished to go with Blanchard. That forced him to reply that it was “out of his power to gratify their wishes, having brought from Europe only 4200 weight of vitriolic [sulphuric] acid, the quantity necessary to effect the ascension, once.”

Adding to the intrigue of this essay, Frederick R. Smith, like General Moylan, is a Lay Trustee of his local Catholic Church. Furthermore, in the early 1960s, Freddy walked to grade school via Cadwalader Avenue. Colonel John Cadwalader (1724-1786) was active in public fairs, a member of the Philadelphia Comision of Safety, Colonel of the city’s “silk stocking” militia company, and in 1776 he had become Colonel of a Pennsylvania militia regiment. Moylan collaborated with Cadwalader during the Revolutionary War war. For example, in “the latter part of September,” 1776, James Allen visited the American army at Fort Constitution or Fort Lee, lodged with Washington, and “found there Reed, Tilghman, Grayson, Moylan, Cadwallader, and others and was very happy with them.” Quoted source: Stephen Moylan (a history) - Martin I. J. Griffin, 140 pages, American Catholic Historical Society, April 1909, Muster-Master General, Secretary and Aide-de-Camp to Washington, Quartermaster General, Colonel of 4th Pennsylvania. Also, see the video John Cadwalader Duels with the Conway Cabal.

Subscribe to Frederick R. Smith Speaks

The Frederick R. Smith blog is the ramblings of an uncommon man in a post-modern world. As a master of few topics, your author desires to give readers a sense of the thoughts of a senior citizen who lived most of his life before the new normal.

This is a NO FB post. Most Ret. Military say BARF. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SHf1w1KAQiQ

Give me a long stretch of open divided freeway, speed is not an issue. Big City driving scares me. Dean now does navigating, as I see better than he does, but uses old routes that are longer, but I feel capable of driving. I truly hate having to drive into Memphis, it terrifies me. Then the 3 hr wait while he sees the Glaucoma doc. Just one of the hardships of living in the country, in the next county.