Discover more from Frederick R. Smith Speaks

First Flight 1793 and the Finest Part 2 - First Launch

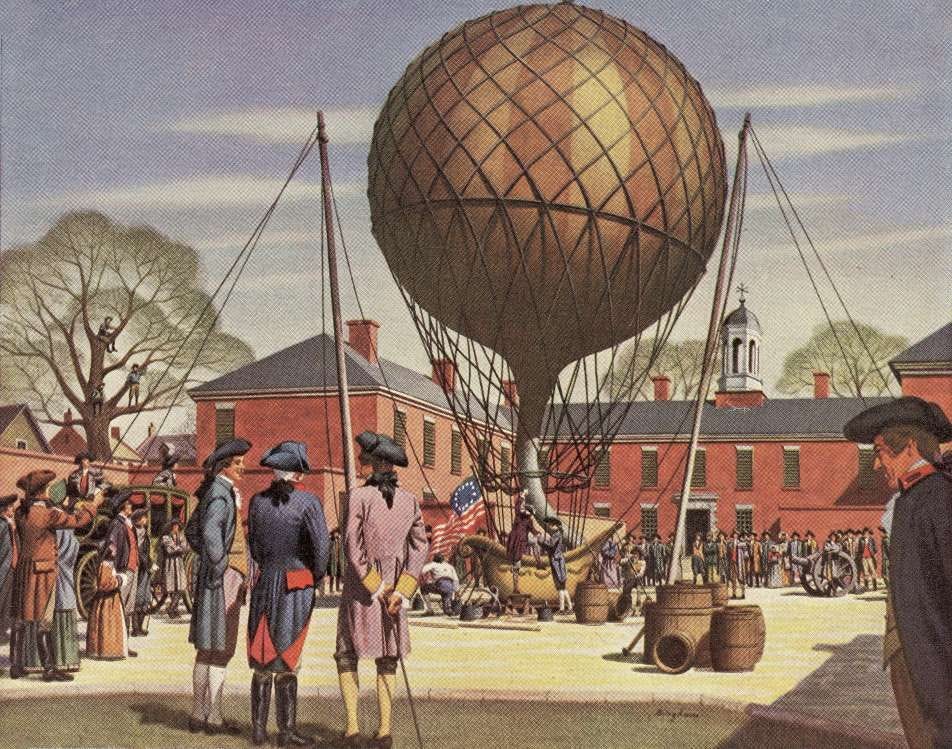

As the seat of Government, virtually the entire Washington Administration, Congress, and the Judiciary were in Philadelphia the day of Blanchard's 45th balloon ascent on January 9, 1793.

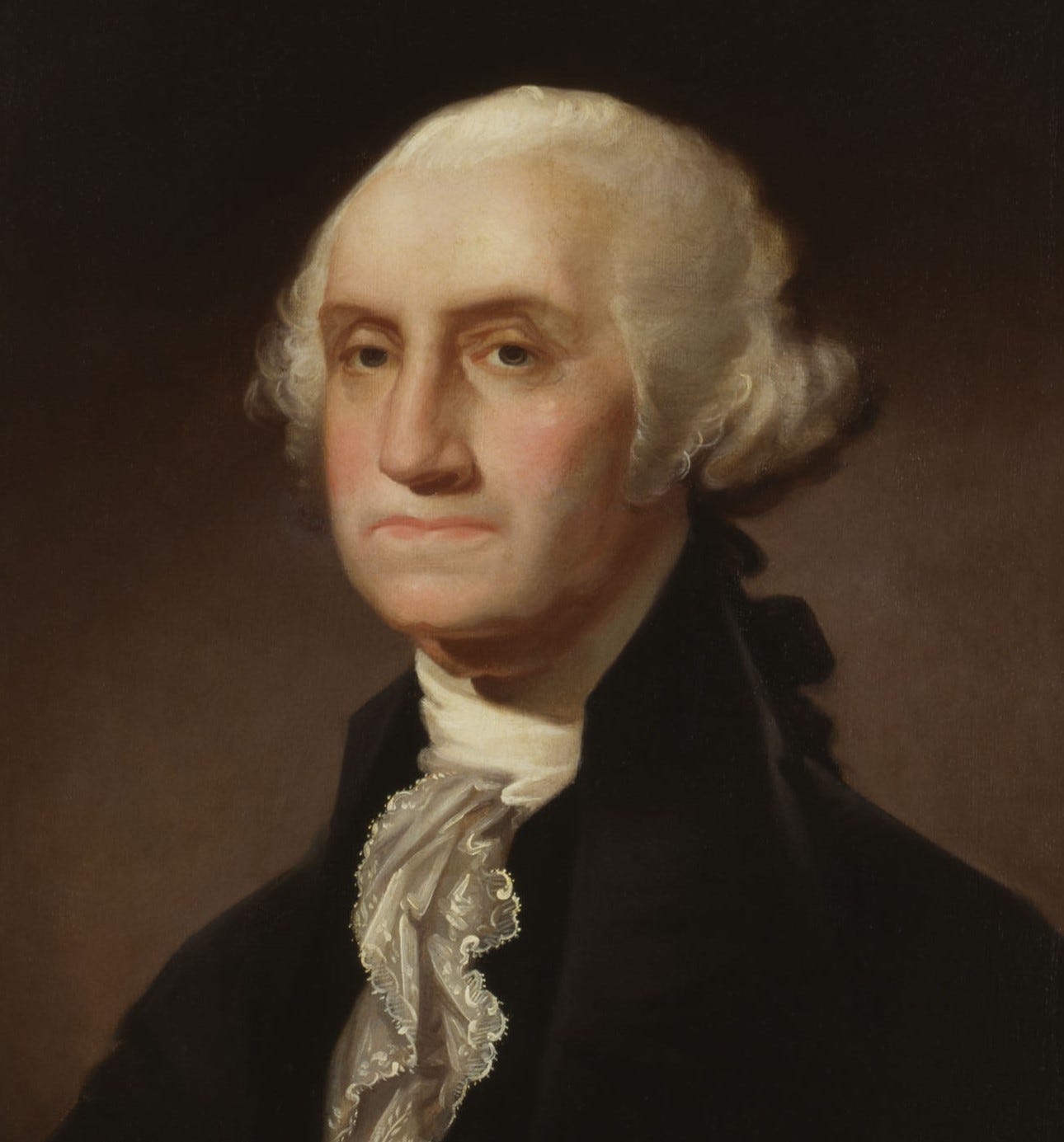

I have only news paper accts. of Air Balloons, to which I do not what credence to give. The tales related of them are marvelous, and lead us to expect that our friends at Paris, in a little time, will come flying thro’ the air, instead of ploughing the ocean to get to America.

George Washington

Part 2 - First Launch

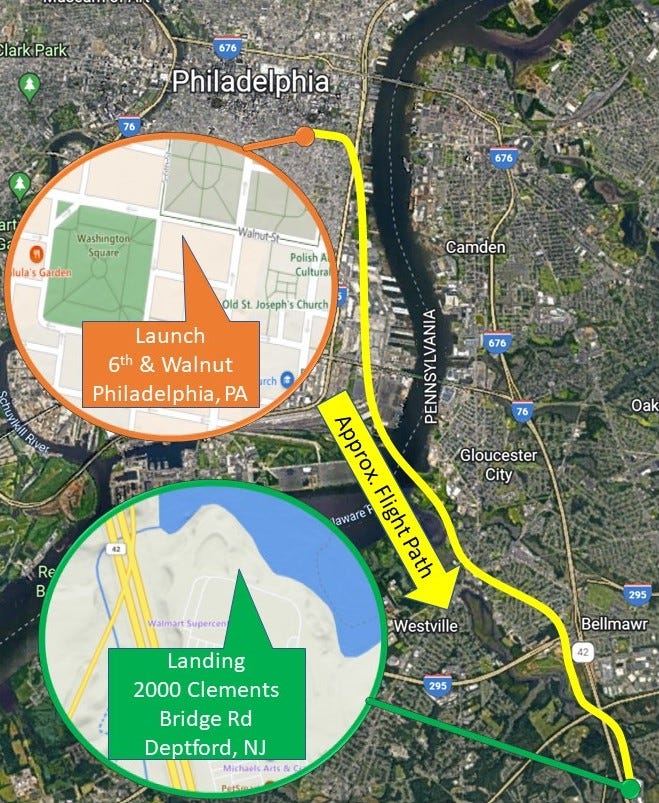

On January 9, 1793, Jean-Pierre-François Blanchard launched his hydrogen-filled balloon. The spectacle occurred at the southeast corner of Sixth and Walnut Street in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. There, Blanchard staged his balloon in the courtyard of the Walnut Street Prison. It was one of the nation’s first urban penal institutions. It confined felons, prisoners of war, Tories, and debtors from 1775 to 1838. Built from Walnut to Locust Street, it was the site of numerous riots. The Eastern State Penitentiary replaced the prison. Today, the Penn Mutual Insurance building locates at this historic spot. Also, see Part 5 (First and Finest) to read about Stephen R. Moylan’s coincidental connection to this historic spot.

The prison courtyard was an essential ingredient that ensured a successful flight. The walls protected the balloon and a hydrogen-making “ventilator” from curiosity seekers. That operation included the pouring of large quantities of water diluted sulphuric acid and water into a barrel of iron filings—tubes and valves to control the resulting outflow of gas.

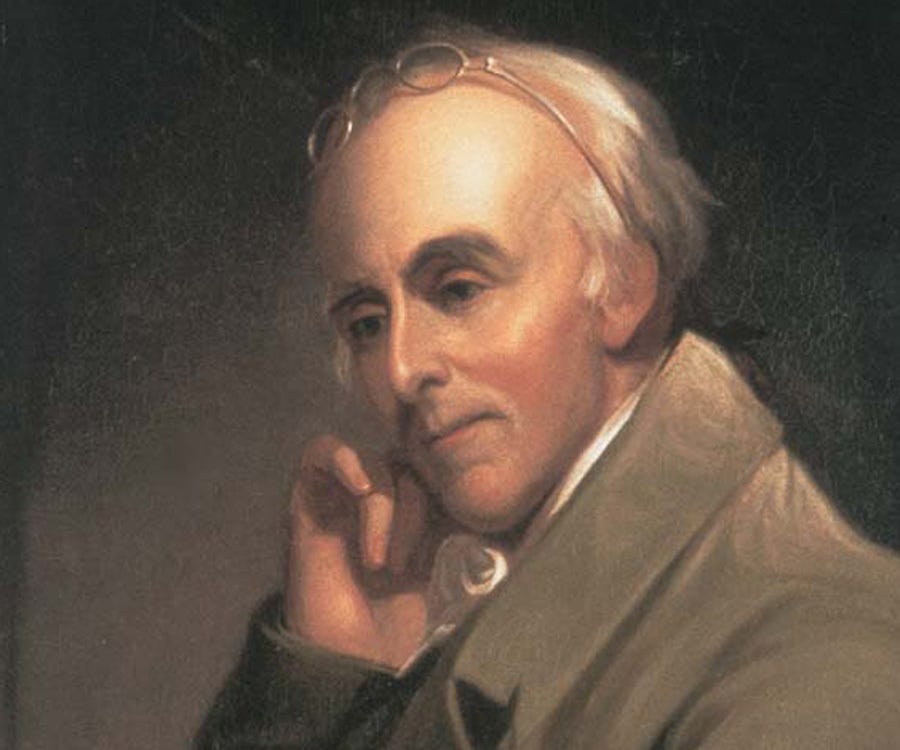

Many local scientists assisted Blanchard with the preparations for his flight. They included Dr. Casper Wistar, Peter Legaux, Dr. David Nassy, Benjamin Franklin Bache, and Dr. Benjamin Rush (signer of the Declaration of Independence). At the time, Dr. Rush was a Professor at the Institutes of Medicine and Clinical Cases at the University of Pennsylvania. As seen later, he also instructed Blanchard on how to conduct an in-flight medical experiment.

This spacious courtyard area was an ideal launching spot among the otherwise crowded cityscape. It also provided a stadium-like setting, thus allowing for the sale of tickets for a close-up view of the launching. At the very high sum for the era, Blanchard sold “front-row” tickets at $5 each. Blanchard also offered $2 seats in a special section behind the others. Proceeds went to Blanchard to pay for the expenses of making the hydrogen gas. Ticket sales for his Blanchard’s flight and donations failed to raise the $500 expenses he said the flight had cost. Ticket sales only provided less than one-fifth of that amount. Approximately 100 spectators attended an area that could have held an estimated 4,800 spectators. Most of the crowd had decided they did not need to view the departure ceremony. They could witness the flight as soon as the daring aeronaut rose in his ‘aerostat’ above the prison walls. Joseph Ravara, Consul General of Genoa in Philadelphia, planned a subscription to fund the aeronaut. That fell far short of the mark.

Several people wanted to go with him, but Blanchard was not about to share this ‘first’ with anyone. He also discouraged those who wanted to follow him on horseback. In a notice in the Federal Gazette, he noted:

If the day is calm, there will be full time to reach the prison court…as…I will ascend perpendicularly, but if the wind blows, permit me, gentlemen, to advise you not to attempt to keep up with me, especially in a country so intersected with rivers, and so covered with woods.

Blanchard’s Journal mentions the presence of George Washington (President 1789-1797)1 and Monsieur John de Ternant, French Minister Plenipotentiary, at the prison courtyard. Washington handed Blanchard his “passport of introduction” just as he entered his “boat” [basket].

The Washington Administration, Congress, and the Judiciary were in the Capitol city of Philadelphia on the day of the launch. The famous woman likey to have seen the flight included Martha Washington, Dolly Todd (Madison), and Betsy Ross.

Blanchard’s “45th Launch,” advertised in advance by the newspapers and word of mouth, prompted people to see the balloon for miles surrounding the flight. With many of the founders serving in government positions, they surely missed Benjamin Franklin. As detailed in Part 1, Franklin saw balloons, wrote about the future of air travel, and passed on April 17, 1790, at 83. His gravesite is a couple of blocks from the launch site. Also, see Benjamin Franklin and Friends Lay the Basis for Manned Flight.

Likely, everyone who lived in Philadelphia at the time and out-of-town visitors saw the launch. Many very distinguished residents were there with congress in session. John Adams was Vice President, and Thomas Jefferson was the Secretary of State. Besides Washington, four future presidents were part of the government. They were John Adams, Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, and James Monroe. Other notables were Alexander Hamilton (Secretary of Treasury), Edmond Randolph (Attorney General), Timothy Pickering (Postmaster-General), and Henry Knox (Secretary of War).

Blanchard’s 45th aerial adventure in Philadelphia occurred ten years after his first flight. He did not speak English, and his letter or “passport of introduction” from Washington proved invaluable. A key motivator for his trip to Philadelphia was his honest view of Washington as a hero. In his Journal, Blanchard detailed the “… gracious reception with which I was welcomed by the hero of liberty, General GEORGE WASHINGTON ...”

The evening before the launch, the sky was clear and calm. Between 4:00 am and 6:00 am, Blanchard recorded a temperature of 30 deg. F.

7:00 am to 8:00 am sky was overcast and hazy with a temperature of 35 deg. F.

9:00 am mist had dissipated with thin clouds impervious to the sun’s rays.

9:30 sun broke through the clouds with a gentle westerly breeze.

9:45 sky was clear with a light breeze from the west with a temperature of 38 deg. F.

The inflation of the balloon with hydrogen gas commenced at 9:00 am, along with a brass band playing music. Two cannons fired every quarter-hour starting at dawn to alert residents. At 9:45 am, a carriage bearing President George Washington arrived. As the dignified chief executive stepped down, the crowd hushed, and 15 cannons fired. Washington handed his “passport of introduction” to Blanchard. A “black dog” accompanied the balloonist in his basket.

At 10:09 am, the sky was clear, there was little wind, calm at the surface, and the hydrogen-filled balloon ascended. The balloon was a yellowish color. Blanchard dressed in a plain blue suit topped by a cocked hat donned with white feathers. As Blanchard entered the basket, he waved the colors of the United States and the French Republic. Then he waved his hat to the thousands gathered to witness the spectacle.

The balloon rose perpendicular to 1,200 feet then the breeze carried it east toward the Delaware River. While ascending higher, the wind took the balloon to a more south route in Philadelphia, paralleling the river. At 10:16 am, Blanchard “let go” of the dangling anchor tied to the basket.2 He recorded that as “a point of observation.” At 10:19 am, the ascent became more rapid, and the winds took the balloon to a more southeast route crossing the Delaware River.

At 10:35, the black dog “... which a friend had entrusted me, seems to feel sick at this height, he attempted several times to get out of the car; but finding no landing place he took the prudent part to remain quietly beside me….” The balloon ascended to the greatest altitude of 5,812 feet. Blanchard captured high-altitude air by pouring liquid out of six bottles and corking them. He also weighed a stone that had weighed 5.5 ounces on land, and at the greatest altitude, it weighed 4 ounces. Following Dr. Benjamin Rush’s instructions, Blanchard took his pulse and recorded the readings.

At 10:38 am, Blanchard noted a temperature of 52 degrees F. with the “air most delightful and quite extortionary for this time of the year.” Philadelphia was in view as a “microscopic object.” He also wrote: “I straightened my stomach with a morsel of biscuit and a glass of wine. I then locked up in the body of my car those instruments that were apt to break.”

Part 3 - “First Landing and Beyond,” is a virtual ride-along with Blanchard as he ascends over the Delaware River, descends to Deptford, New Jersey, and a review of the rest of his life.

Author and publisher, Frederick R. Smith

For more transportation connections to Washington, also see “Why The Name, George Washington’s Railroad?” section of the online essay Chesapeake & Ohio Railway: “George Washington's Railroad”

Blanchard noted the “letting go of the anchor” mid-flight in his log. Therefore, paintings of the landing showing an anchor might be artistic license.