Discover more from Frederick R. Smith Speaks

The Second Day of July 1776

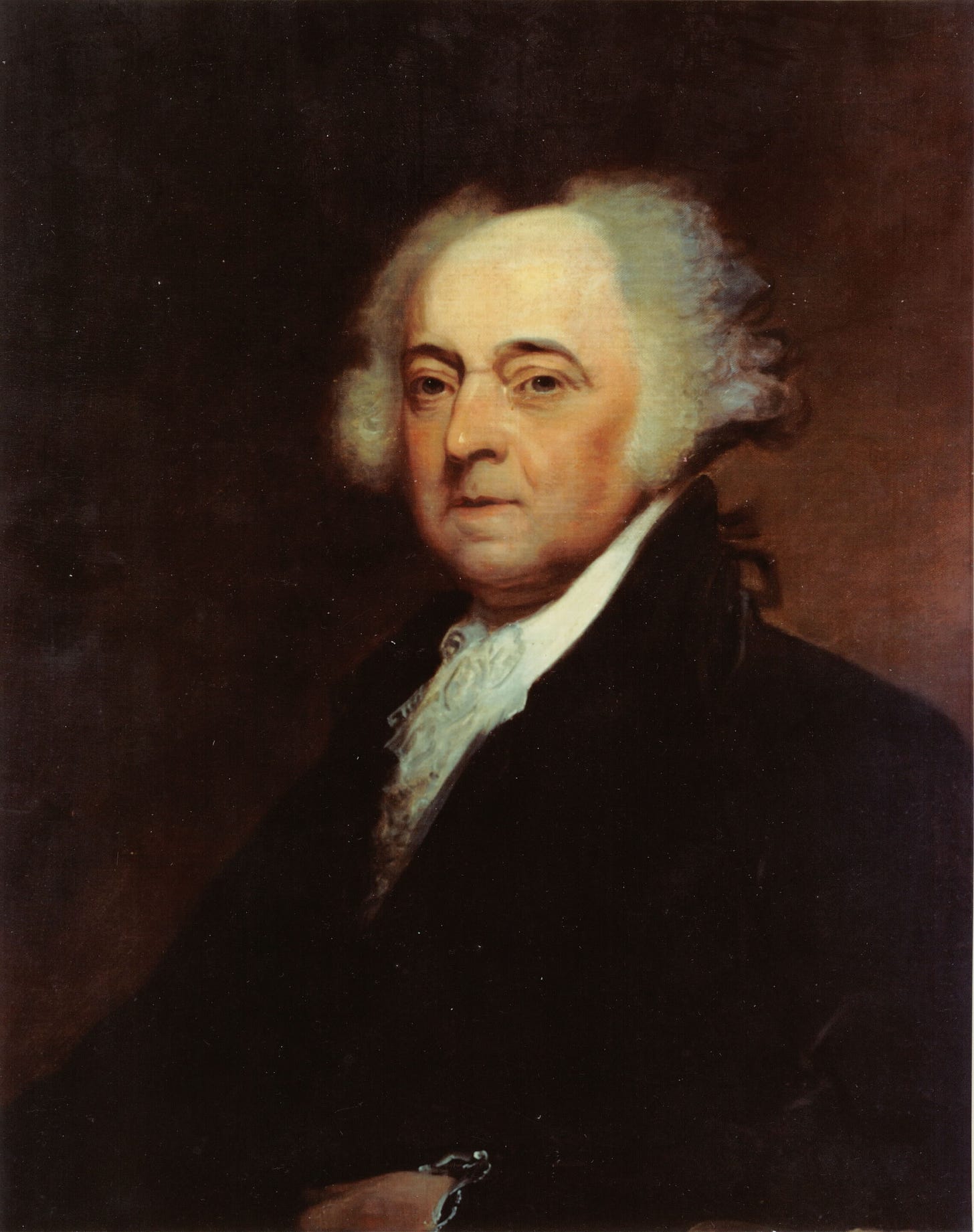

The second day of July 1776 will be the most memorable epoch in the history of America. John Adams

The second day of July 1776 will be the most memorable epoch in the history of America. I am apt to believe that it will be celebrated by succeeding generations as the great anniversary festival. It ought to be commemorated as the Day of Deliverance by solemn acts of devotion to God Almighty. It ought to be solemnized with pomp and parade, with shows, games, sports, guns, bells, bonfires, and illuminations from one end of this continent to the other from this time forward forever more.

John Adams

Repost July 3, 2022

WE celebrate July 4, 1776, as the birthday of the United States. It is fitting to consider the chain of events that lead to this tradition as a historical note.

Ever since the founding of the original thirteen colonies and the conclusion of the War of 1812, several events strained the new world’s relationship with the Crown. In early 1776, the colonists started to call for the end of rule by the King openly. Thomas Paine’s booklet “Common Sense” was published in January 1776, and it spurned a sentiment for independence throughout the colonies.1 In mid-May, John Adams from Massachusetts suggested to the Second Continental Congress in Philadelphia that colonies should form new independent governments. On June 7, Virginia delegate to the Continental Congress, Richard Henry Lee, submitted this resolution:

These United Colonies are, and of right ought to be, free and independent States, that they are absolved from all allegiance to the British Crown, and that all political connections between them and the State of Great Britain is, and ought to be, totally dissolved. That it is expedient forthwith to take the most effectual measures for forming foreign alliances. That a plan of confederation be prepared and transmitted to the respective colonies for their consideration and approbation.

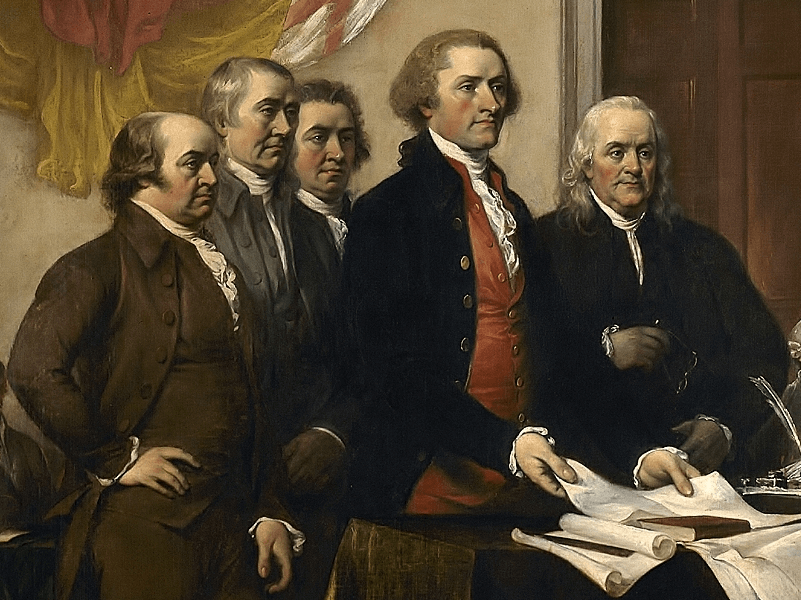

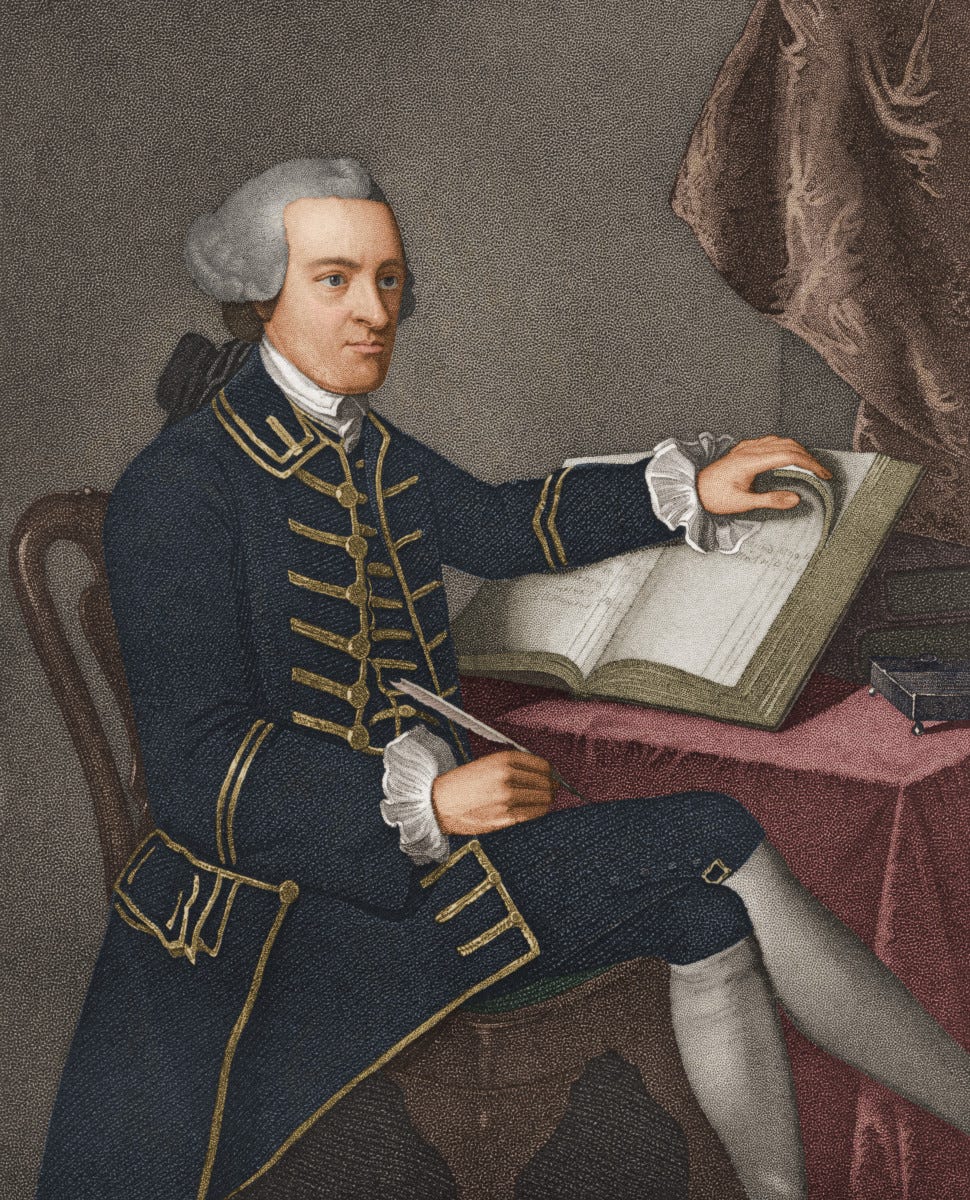

At this point, Pennsylvania and South Carolina opposed this measure, while New York abstained. The remaining nine colonies favored Lee’s resolution. That nudged Congress towards a declaration, and a “committee of five” was appointed to draft a document. The committee members included John Adams (Massachusetts), Roger Sherman (Connecticut), Robert R. Livingston (New York), Thomas Jefferson (Virginia), and Benjamin Franklin (Pennsylvania).

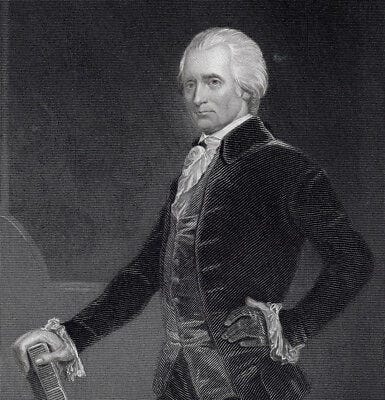

The committee met many times between June 11 and June 28 and finally tapped Jefferson to write the draft. Jefferson, facing a deadline, completed the draft in just three days.

Later in life, Adams recalled the conversation with Jefferson where he gave the reasons why he should not do the writing, telling the Virginian that he should do it:

Reason first: you are a Virginian, and a Virginian ought to appear at the head of this business. Reason second: I am obnoxious, suspected, and unpopular. You are very much otherwise. Reason third: You can write ten times better than I can.2

Jefferson and Franklin reviewed the first draft and made minor changes; then, the entire committee submitted the draft to Congress for review. On June 28, 1776, the committee of five advanced to the Second Continental Congress “A Declaration by the Representatives of the United States of America in General Assembly.” With the Declaration still on the sidelines, on July 1, nine Colonies voted for independence.

It was on July 2 that a 12-0 vote occurred. New York abstained, awaiting instructions from its constituents, but on July 9, the State Provincial Congress voted to “join with the other colonies in supporting” independence. On July 3, Adams wrote about the previous day in a letter to his beloved Abigail that:

The second day of July 1776 will be the most memorable epoch in the history of America. I am apt to believe that it will be celebrated by succeeding generations as the great anniversary festival. It ought to be commemorated as the Day of Deliverance by solemn acts of devotion to God Almighty. It ought to be solemnized with pomp and parade, with shows, games, sports, guns, bells, bonfires, and illuminations from one end of this continent to the other from this time forward forever more.

Congress reviewed the committee’s draft line-by-line for two days and made significant changes. Congress deleted a few passages of the draft and amended others but outright rejected only two sections:

A derogatory reference to the English people, and

Passionate denunciation of the slave trade.3

As Jefferson reported, the latter section was left out to accede to the wishes of South Carolina and Georgia, who wanted to continue the importation of enslaved people. Another significant change was the addition of various references to God. Jefferson was unhappy with these changes. However, he said very little in Congress in step with his character while modifying the document.

On July 4, 1776, the Second Continental Congress adopted “The unanimous Declaration of the thirteen United States of America.” By tradition, we refer to it as simply the “Declaration of Independence.” Congress authenticated the document and ordered it engrossed on parchment (or animal skin) on this same day. Congress also ordered it to be proclaimed and distributed. The Congressional secretary, Charles Thomson (Pennsylvania), read the document.

Only Thomson and John Hancock, President of Congress (Massachuesstes), signed it at this point.

On July 5, the printer John Dunlap provided prints of the Declaration to the delegates who were busy sending copies to their friends. The following day, the Pennsylvania Evening Post printed the entire text of the Declaration on its front page. At noon on July 8, the gathered crowd at the State House listened to a public reading of the Declaration by Colonel John Nixon. Celebrations continued the rest of the day and through the night.

It was not until August 2 that some delegates signed the one large parchment of the Declaration.4 The last to sign, Thomas McKean of Delaware, did not place his signature on the parchment until January 1777.

John Adams (2nd President, 91) and Thomas Jefferson (3rd President, 83) both passed away on July 4, 1826. That coincidental event occurred on the 50th anniversary of the adoption of the Declaration of Independence. Though Jefferson had died five hours earlier, Adams’ last words were, “Thomas Jefferson still survives.”

As an appendix, I am pleased to insert a link to KW Norton Border’s great essay about the Declaration of Independence:

Major printed source - John Adams by David McCullough, Simon and Schuster, 2001.

Cogent author and publisher, Frederick R. Smith

John Adams was not enamored with Paine’s work as he felt it “tore down rather than built up.” Paine’s work was a harbinger of his future writings critical of Christianity. Suggested reading: The Corruption and Debauchery of Thomas Paine.

The accuracy of Adams’ statement is lost to history as Jefferson claimed the committee as a whole met and chose him to write the draft.

Also see Frederick R. Smith Speaks, The Sin of Slavery.

Late in life, John Adams and Thomas Jefferson claimed that the Declaration’s signature occurred on the 4th of July. However, other historical documents indicate otherwise.

Subscribe to Frederick R. Smith Speaks

The Frederick R. Smith blog is the ramblings of an uncommon man in a post-modern world. As a master of few topics, your author desires to give readers a sense of the thoughts of a senior citizen who lived most of his life before the new normal.

Beautifully writen, Fred. Should be taught in our schools

McCullough, fantastic author. Thanks, Fred.