1918 Railroads Railroaded

This essay explores the important role of the American railroads during World War I and a link back to the creation of the Federal Reserve.

Words: 4,177 ~ Read time: 17 min

Foreword

This essay explores the vital role of the American railroads during World War I. Government intervention in railroad businesses and the involvement of a critical personality instrumental in creating the Federal Reserve make for an intriguing and entertaining read.

Executive Summary

Introduction: In 1917, the U.S. entered World War I, prompting a need for efficient rail transportation of essential materials. Financial challenges in the railroad industry, rooted in the aftermath of the Panic of 1907, exacerbated by labor shortages and increased costs during the war, led to operational difficulties.

Creation of USRA: President Wilson established the United States Railroad Administration (USRA) in 1918 to address the crisis, assuming control of the nation’s railroads. The USRA aimed to prevent congestion and wasted equipment and ensure unified direction in equipment handling and maintenance.

Challenges and Achievements: The USRA faced difficulties, including locomotive shortages and the need for standardized equipment. Although the twelve chosen designs aimed at minimizing variety, they faced criticism for failing to achieve this goal effectively. The controversy also stemmed from perceived government interference in business.

Defects and Financial Burden: The USRA incurred a substantial deficit during its operations, leading to controversy. Political factors, including opposition from the Republican Party, influenced public perception. The analogy between the deficit and wartime sacrifices emphasized the context but did not alleviate criticism.

Media and Industry Opposition: The controversy extended to the standardization of rolling stock, particularly locomotives. While generally accepted, freight car and locomotive standardization faced opposition from industry figures and publications like Railway Age. Arguments against standardization included concerns about hindering progress and complicating maintenance.

Railroad Complaints: The USRA faced challenges maintaining standardized locomotives due to shopmen’s resistance and complaints. A 1920 booklet highlighted various criticisms, often lacking sufficient support. Over time, as shopmen became more familiar with USRA locomotives, initial challenges were overcome, and the standardized designs demonstrated long-term success.

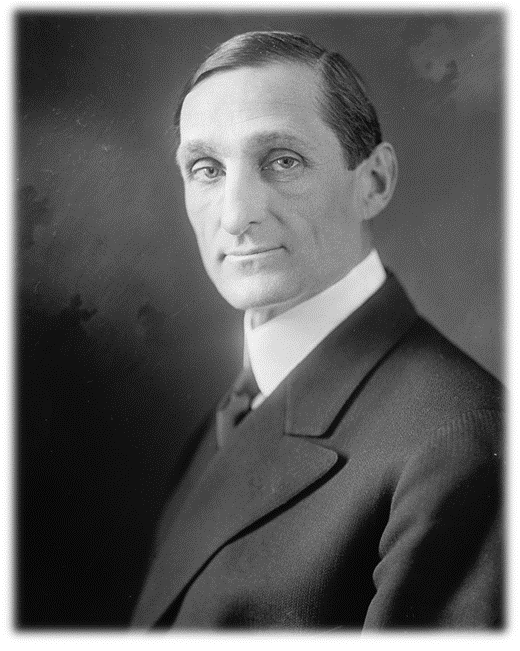

William Gibbs McAdoo: William Gibbs McAdoo was a prominent American lawyer, politician, and statesman known for his significant contributions during the early 20th century. His political journey led him to Washington, D.C., where he served as an assistant secretary of the Navy under President Woodrow Wilson, marking the beginning of a close association with Wilson. In 1913, McAdoo became the Secretary of the Treasury, playing a crucial role in passing the Federal Reserve Act of 1913, reforming the nation’s banking system. During World War I, he served as the first director general of the USRA, managing the nation’s railways and facilitating efficient troop and resource transportation.

Introduction

Amtrak is short for the National Railroad Passenger Corporation. Following the 1970 Rail Passenger Service Act, the government established Amtrak in 1971. The goal was to merge and revitalize intercity passenger rail services. Amtrak is a government-owned and funded money-losing corporation. It receives federal funding and generates revenue through ticket sales. The government plays a significant role in financing, route decisions, and oversight. Arguably, that makes it a nationalized operation because it involves government ownership, support, and control.

Government control allows the government to regulate and influence industry operations. The approach chosen depends on the specific goals and circumstances of the government at the time. Much of Amtrak’s trains operate over private railroads. That gives the government the ability to use the term “quasi-government.” It mitigates the need to call it nationalization. With Amtrak as an example, let’s take a historical trip to another experiment in “quasi-nationalization.”

In 1917, the United States entered World War I. President Woodrow Wilson delivered a war message. It prompted the nation to mobilize and support its allies abroad. The nation’s railroads transported essential materials. Goods included food, supplies, and munitions. Yet, the railroads were already facing challenges. President Samuel Rea of the Pennsylvania Railroad emphasized extensive terminal facilities.

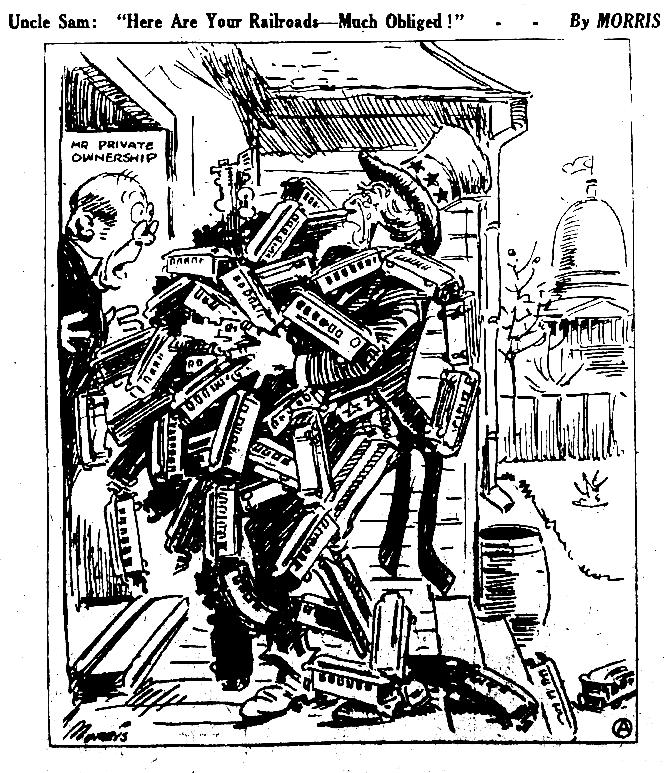

In 1917, under the authority of the Federal Control Act, they established the United States Railroad Administration (USRA).1 The USRA took over operational control. That ensured efficient transportation of troops and resources during the war. USRA controlled pricing, schedules, and other operations. Yet, private companies still owned the infrastructure. Thus, that experiment stopped short of nationalization.

Congress passed the Railroad Control Act into law in March 1918. The government would return control of the railroads to their owners within 21 months of a peace treaty. The owners would receive compensation for the usage of their property. So, they disbanded the USRA two years later, in March 1920. The railroads controlled their property once again.

History of Crisis

The railroads’ financial woes had roots in the aftermath of the Panic of 1907. By 1915, a $4 billion investment increased earnings. Yet, the railroads struggled to meet operating costs, payroll, and taxes. They accumulated a large deficit. The annual interest charges further strained their financial health.

The rigid structure of ratemaking and over-regulation persisted until the passage of the Esch-Cummins Act in 1920. This act acknowledged the carriers’ need for enough revenue. It allowed formal combinations and pooling agreements. That provided some relief to the struggling railroads.

During World War I, railroads faced more challenges. Labor shortages and increased costs were due to the implementation of the Adamson Act (1916). The act mandated an eight-hour workday for train and engine crews, contributing to rising labor expenses. The registration and conscription of men for the war effort further exacerbated the labor shortage. Unlike World War II, it saw the emergence of a significant female workforce.

The surge in business from 1916 onwards, marked by a 32% increase in ton-miles, left the railroads unprepared. A shortage of railcars developed, causing congestion at terminals along the Atlantic coast. Insufficient capacity and facilities led to a backlog of unloaded cars. The railroads’ desire for return loads added operational challenges.

By February 1917, 145,000 cars had accumulated at terminals. USRA Director-General William G. McAdoo (see below) noted that many railroads’ rolling stock was in poor condition. American railroads were not ready for war. They needed development and improvement.

Breakdown in Winter 1917-1918

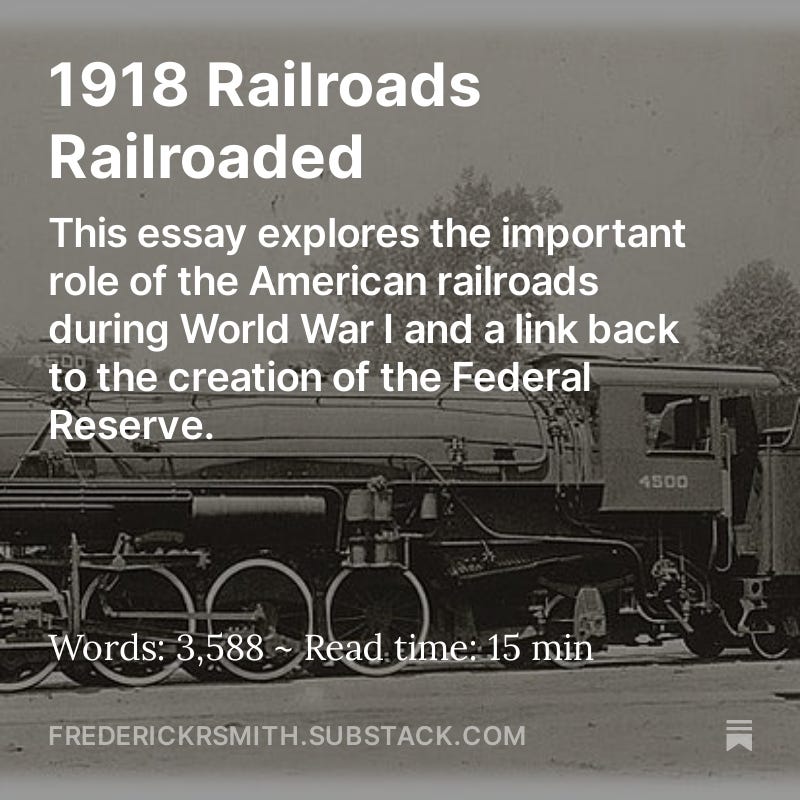

President Wilson acted to address an impending crisis in the railroad industry. He recognized the need for unprecedented cooperation. Despite emphasizing competition, the Interstate Commerce Commission was historical. Wilson established the War Industries Board (WIB). He did so to ensure collaboration and preserve competition. Around seventy railroad presidents convened in Washington within five days of the Declaration of War. They selected five members to form the WIB. It granted “power of attorney” over 635 sizable railroads to override individual interests.

Dynamic CEOs, such as Fairfax Harrison (Southern Railway), Julius Kruttschnidt (Southern Pacific), Howard Elliot (New York, New Haven, & Hartford), Samuel Rea (Pennsylvania Railroad), and Hale Holden (Chicago, Burlington and Quincy Railroad), led the WIB. Ex officio members Daniel Willard (Baltimore & Ohio) and Edgar E. Clark (Interstate Commerce Commission) also served. They relied on persuasion, education, and occasional apologies to influence railroads. Yet, the WIB faced challenges as many companies resisted cooperation, fearing revenue loss. Individual railroads prioritized their interests. The WIB needed more authority to enforce its directives. A significant issue was the issuance of priorities for “essential” shipments.

By the end of 1917, 85% of Pittsburgh Division of the Pennsylvania Railroad traffic moved under priority orders. The eastern lines experienced a surplus of idle-loaded cars, shortages of 158,000 cars for loading, and a looming coal famine in New England. The harbors along the Eastern seaboard experienced congestion. Ships couldn’t leave because of coal shortages caused by railroad congestion. Yard congestion compounded these issues. Ports had inadequate storage facilities. More cars and locomotives were also needed. Railroad workers demanded higher wages. Severe weather in December 1917 almost brought railroading to a standstill. It disrupted the supply chain for ships heading to Europe. That led to the necessity of federal government intervention. It also led to establishing federal control as the only viable option.

At that time, 441 corporations owned the 260,000 route-mile rail network in the United States. The government acted swiftly when the 2,905 companies and subsidiaries that owned 397,014 miles of track refused to cooperate (with each other) and caused a standstill on the rails. By late 1915, approximately one-sixth of the country’s railroad trackage was bankrupt. That was due to excessive expansion by investors. The national railway investment totaled $17.5 billion. The railroads financed over half ($8.75 billion) through debt. Its estimated value was $16 billion.

Creation of USRA

In December 1917, President Wilson assumed control of the nation’s railroads. He did this through the Army Appropriations Act of 1916. He established the United States Railroad Administration (USRA) on January 1, 1918. The Federal Control Act passed in March 1918, appropriated funds for railroads. It also guaranteed compensation. The USRA aimed to prevent clogged terminals and wasted equipment. It also sought to ensure unified direction in equipment handling and maintenance.

The Railway Administration Act became law on March 21, 1918. It affirmed Wilson’s 1917 nationalization order. Wilson appointed his son-in-law, William Gibbs McAdoo, as the first Director General of the USRA. It was operational until March 1920.

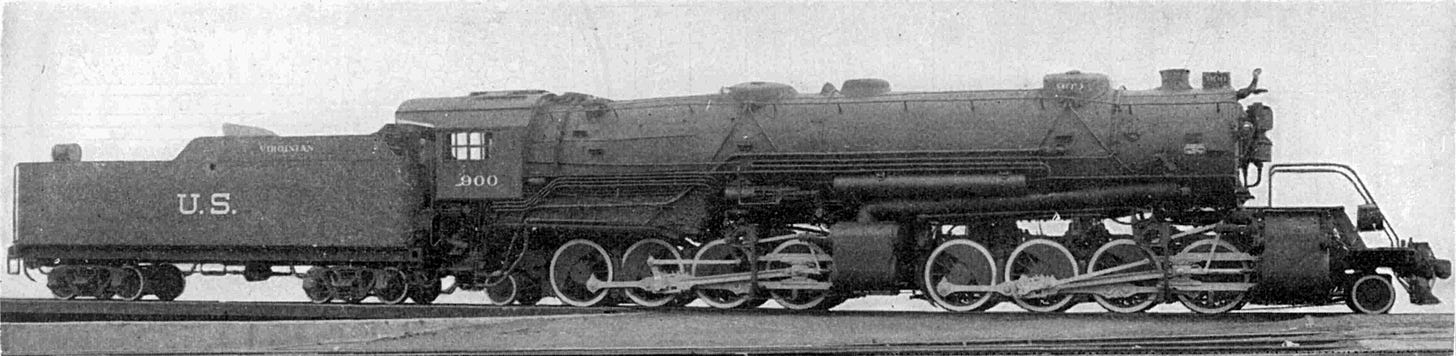

In 1919, Walker Hines, the USRA director-general, highlighted two achievements. They were controlling traffic to prevent congestion. They were also providing unified direction in equipment handling. At the start of federal control, there were shortages of locomotives. The late delivery of the ordered locomotives for U.S. forces and allies in Europe caused this.

During World War I, Russia bought 857 2-10-0 Decapods from the United States. The War Department held up delivery of the last 200 because of the Bolshevik Revolution in 1917. They converted the locomotives from the Russian 5-foot gauge to the 4 feet 8-½ inch standard gauge. United States railroads then leased them to help reduce power shortages. Regions in need received the surplus domestic locomotives. Cooperation with the “mechanical crafts” expedited repairs. To further address deficiencies, the USRA diverted some locomotives and expedited the rehabilitation of others.

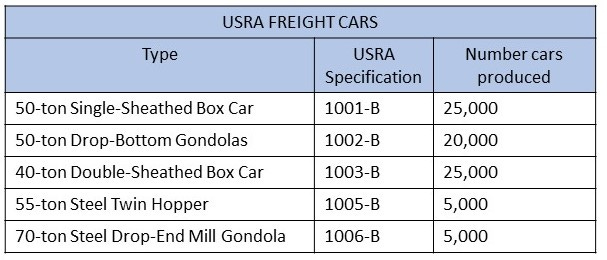

The USRA purchased standardized freight cars and locomotives. They aimed for sound designs meeting various railroad needs while minimizing types. They deemed the twelve locomotive designs valuable.

The USRA Standard Locomotives and Cars

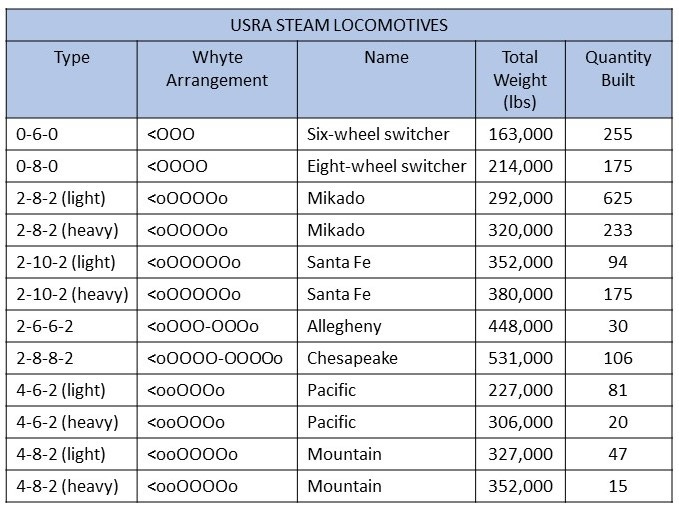

Based on their wheel arrangement, builders classified North American steam locomotives. They use a system called “The Whyte System.” This classification method assigns numbers to the locomotive’s leading, driving, and trailing wheels. The first number represents the number of leading wheels. The middle number(s) show the number and arrangement of driving wheels. The last number signifies the count of trailing wheels, typically positioned under the firebox. For instance, a “2-8-4” or <oOOOOoo designation signifies: - two leading wheels (one axle), - eight driving wheels (four axles), and - four trailing wheels (two axles). Including a “T” at the end denotes a tank engine, distinguishing it from a conventional tender engine.

Frederick Methvan Whyte was a Dutch mechanical engineer for the New York Central. He originated this locomotive classification system. The spelling “Whyte” reflects the Dutch rendition of his name. In railroad literature, you may encounter the Anglo-Saxon spelling “F. M. White.” The first user of each wheel arrangement named most of the wheel arrangements.

Steam turbine electric locomotives have adapted this classification system. It aligns with the terminology used for diesel-electric locomotives. But, there is no standardized classification system for geared locomotives. Examples include Shay, Heisler, and Climax.

The USRA developed 12 designs:

Builders designed the light versions with an axle load of 54,000 lb. Most railroads used them. The designers developed the heavy versions with the largest axle load of 60,000 lb. They were for railroads with lines built for heavy haul.

The USRA placed orders for 555 locomotives with American Locomotive Works. They also ordered 470 from Baldwin Locomotive Works. That order totaled 1,025 locomotives. With more orders, the total came to 1,856 locomotives. Both builders constructed the light Mikado in the beginning. The USRA soon changed the order so that both builders would make all 12 locomotive types. USRA also built box, gondola, and hopper cars.

Deficits

The USRA faced significant criticism after the end of government control. That was due to a substantial deficit of almost a billion dollars during its operations. This financial burden arose from the government’s attempt to preserve the corporate identities of the railroads it took over. The government paid rent for their use, determined by each railroad’s average net earnings over a previous three-year period. The government was responsible for maintaining their condition. Yet, labor, materials, and fuel costs increased. The government’s rate increases were not enough. That led to a 750 million dollar deficit over 26 months.

Political factors played a role in the controversy surrounding the USRA. President Wilson was a Democrat. The majority Republican Party opposed him. His progressive policies, such as income tax, banking reform, and anti-trust legislation, had not endeared him. The influential financial interests in the country shunned him. Wilson appointed William G. McAdoo as the director-general of the USRA. His marriage to Wilson’s youngest daughter, Eleanor Randolph Wilson, brought extra scrutiny.2 His association with various reforms also brought additional scrutiny. In his memoirs, McAdoo defended his tenure. Controversy persisted. Politics influenced perceptions of the USRA.

McAdoo drew an analogy between the deficit and the cost of bombarding the enemy during the Meuse-Argonne offensive. That emphasized the wartime context and the sacrifices made for victory. Yet, the deficit remained contentious, contributing to the USRA controversy.

Media and Industry Opposition

The USRA’s program to standardize rolling stock, particularly locomotives, sparked controversy. Differing opinions arose on the necessity and feasibility of standardization. The industry generally accepted freight car standardization. It was practical to use uniform dimensions and interchangeable parts. Yet, locomotive standardization faced opposition from the trade press and locomotive builders. For example, the president of Baldwin Locomotive Works, Alba B. Johnson, opposed it.

Railway Age, a prominent industry magazine then and now, argued against locomotive standardization. It claimed that each railroad had unique needs requiring customized designs. They also argued it would compromise efficiency. Railway Age opposed the standardization, saying it would come too late to help the war effort. The magazine suggested a better approach. It involves allowing roads to order existing designs based on their preferences. This approach proved successful for the American military.

Despite this opposition, there were advocates for standardization. They highlighted benefits. For example, it is easy to transfer locomotives between different sections of a railroad. The debate continued. Some locomotive designs of the period resembled the twelve types established by the USRA.

Johnson made a significant critique against standardization. He argued that it would hinder progress by preventing changes based on experience or invention. Johnson also expressed concerns about potential adverse effects on accessory manufacturers. He also worried about increased complications in locomotive maintenance.

USRA faced criticism for its standardization of locomotives. Critics argued against its timing, method, and impact on the war effort. But, the long-term benefits of standardization became evident. That emphasizes the hindsight perspective. The advantages of uniformity and efficiency in the industry outweighed short-term challenges.

Railroads Complain

The USRA faced challenges in maintaining standardized locomotives. These arose due to shopmen’s resistance, ignorance, or reluctance to adapt to new standards. A 1920 booklet, “Comments and Criticisms on Standardized Locomotives,” criticized USRA locomotives. Railroads owning them had various complaints. Many of these complaints lacked enough support. The standardized equipment varied from individual road standards and practices. That formed the basis for them.

The USRA acknowledged some valid complaints related to design or material defects. They took steps to remedy these issues. Yet, most criticisms focused on “specialties,” patented devices essential to locomotives. They were often expressions of frustration or preference for individual road practices.

Some railroads exhibited pettiness in their complaints, criticizing minor details. Later, they purchased similar locomotives from commercial builders. Over time, shopmen became more familiar with USRA locomotives. People saw aberrations, but in time, they accepted them as standard practice. Despite initial challenges and controversies, the USRA locomotives demonstrated sound design. They also showed quality construction and adaptability. They remained in service past World War I and through World War II. These locomotives had long and active lives. Their widespread use attested to the success of the standardization program.

After the war, labor unions advocated for the continued nationalization of the railroads. Wilson or the public did not support this stance. The U.S. did not take part in the Treaty of Versailles in 1919. The Treaty would have provided the legal basis for returning the railroads to private ownership. Under the Railway Administration Act, they would have done this. So, lawmakers introduced a bill to help return the railroads to private ownership.

In February 1920, Congress passed the Esch-Cummins Act (Railroad Transportation Act. It increased the power of the Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC) over the railroads. The authority of the USRA concluded on March 1, 1920. The ICC can approve or reject railroad mergers and set rates. It also reviewed abandonments of service and assumed extra oversight responsibilities.

The ICC has the power to approve or reject railroad mergers. It also sets rates, reviews service abandonments, and takes on more oversight tasks. In the end, the government provided financial support to the railroads post-handover. That ensured their financial stability following the restoration of control.

William Gibbs McAdoo

William Gibbs McAdoo (1863–1941) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman. He is best known for his significant contributions to the United States during the early 20th century. McAdoo grew up in a family with legal and political traditions.

Born in Marietta, Georgia, he relocated with his family to Knoxville, where his father worked at the University of Tennessee. McAdoo spent three years attending the university before moving to Chattanooga. There, he engaged in law practice, immersed himself in Democratic politics, and invested in local development. During this time, he developed a lasting fascination with public transportation.

In 1889, McAdoo embarked on an ambitious project to electrify Knoxville’s streetcar system. Unfortunately, the endeavor failed, leaving him penniless and facing embarrassment.3 Undeterred, he made a fresh start by moving to New York City, where he established himself as a successful corporate attorney. Despite the setback, McAdoo maintained his interest in transportation.

In 1901, he took the lead in a daring initiative to construct a series of railroad tunnels beneath the Hudson River. The successful completion of the Hudson Tubes brought McAdoo significant recognition.4 It established him as a trusted advisor to then-New Jersey Governor Woodrow Wilson.

His political aspirations led him to Washington, D.C., where he worked as an assistant secretary of the Navy under President Woodrow Wilson. This position began his close association with Wilson. McAdoo soon became a crucial key figure in the Wilson administration.

In 1913, McAdoo took on the role of Secretary of the Treasury, a position he held throughout both of Wilson’s terms as president. As Secretary of the Treasury, McAdoo played a crucial role in the passage of the Federal Reserve Act of 1913. The act reformed the nation’s banking and monetary system. His efforts earned him a reputation as a skilled and innovative financial policymaker. He served as ex-officio chairman of the Federal Reserve Board of Governors from 1913 to 1918.

During World War I, McAdoo’s responsibilities expanded as he served as the first director general of the USRA. In this role (1918-1919), he was vital in managing the nation’s railways during the war. He helped to ensure the efficient transportation of troops and resources. In 1919, he was crucial in establishing the Hollywood studio United Artists. At the time, he served as a lawyer for director D. W. Griffith and renowned actors such as Charlie Chaplin, Douglas Fairbanks, and Mary Pickford.

Besides his government roles, McAdoo sought the Democratic presidential nomination in 1920. Yet, he was unsuccessful. He returned to private law practice, working in New York City and remaining active in political and financial circles.

McAdoo continued his political career. He sought the Democratic presidential nomination again in 1924 and 1932 but was unsuccessful both times. Despite these setbacks, McAdoo maintained influence within the Democratic Party. He served as a U.S. Senator (D-CA) 1933-1938.

William Gibbs McAdoo intertwines his legacy with his contributions to financial reform. He managed the nation’s railways during World War I and stayed involved in American politics. His dedication to public service and his impact on monetary policy solidifies his place as a notable figure. That includes American political and economic history. He was influential during a critical period in U.S. history. He passed away on February 1, 1941, leaving a legacy of service and leadership.

To listen to a speech by William Gibbs McAdoo following the U.S. declaration of war in 1917, click here.

Conclusion

Despite initial controversy and challenges, the USRA’s standardization efforts, both in equipment and operations, successfully met the demands of wartime transportation. The long and active life of the standardized locomotives and their lasting impact on the industry attested to the soundness of the designs and the program’s adaptability.📕

Sources

A Brief History of Greater Emory Place ~ Wayback Machine

Battle of Depot Street ~ wikious.com

Eleanor Wilson Weds W. G. M’Adoo ~ New York Times May 8, 1914

Guide to North American Steam Locomtoves Revised Edition ~ George H. Drury 335 pages, Kalmbach Books, 2015

Hudson and Manhattan Railroad Tunnel ~ American Society of Civil Engineers

On this day, Woodrow Wilson seizes the nation’s railroads ~ National Constitution Center, December 26, 2021

Uncle Sam’s Locomotives: The USRA and the Nation’s Railroads ~ Eugene L. Huddelson, 232 pages, Indiana University Press, 2002

William G. McAdoo ~ federalreservehistory.org

William Gibbs McAdoo ~ The Kentucky Focus

William Gibbs McAdoo ~ Volopedia

William Gibbs McAdoo 1863-1941 ~ The Tennessee Encyclopedia of History and Culture

I warmly encourage you to consider becoming a paid subscriber if you have the means. Tips are appreciated, too. Regardless of your choice, your support is deeply appreciated. From the bottom of my heart, thank you for your invaluable support!

USRA should not be confused with the United States Railway Association or Federal Railroad Administration.

The United States Railway Association, established through federal legislation, was a government-owned entity responsible for overseeing the establishment of Conrail. Conrail, a railroad corporation, was intended to acquire and manage financially troubled freight railroads. The later USRA operated from 1974 to 1986.

The Federal Railroad Administration (FRA), housed within the United States Department of Transportation (DOT), was formed under the Department of Transportation Act of 1966. The FRA’s objectives encompass formulating and enforcing rail safety regulations, administering railroad assistance programs, undertaking research and development to enhance railroad safety and national rail transportation policy, facilitating the rehabilitation of Northeast Corridor rail passenger service, and consolidating government support for rail transportation activities.

McAdoo entered matrimony on November 18, 1885, with his first wife, Sarah Hazelhurst Fleming. The union resulted in seven children: Harriet Floyd McAdoo, Francis Huger McAdoo, Julia Hazelhurst McAdoo, Nona Hazelhurst McAdoo, William Gibbs McAdoo III, Robert Hazelhurst McAdoo, and Sarah Fleming McAdoo. Sarah passed in 1912.

On May 7, 1914, McAdoo wed Eleanor Randolph Wilson, the president’s daughter, at the White House. They had two daughters: Ellen Wilson McAdoo and Mary Faith McAdoo. McAdoo’s second marriage ended in divorce in July 1935. Remarkably, at nearly 72 years old, he entered a third marriage with 26-year-old nurse Doris Isabel Cross in September 1935.

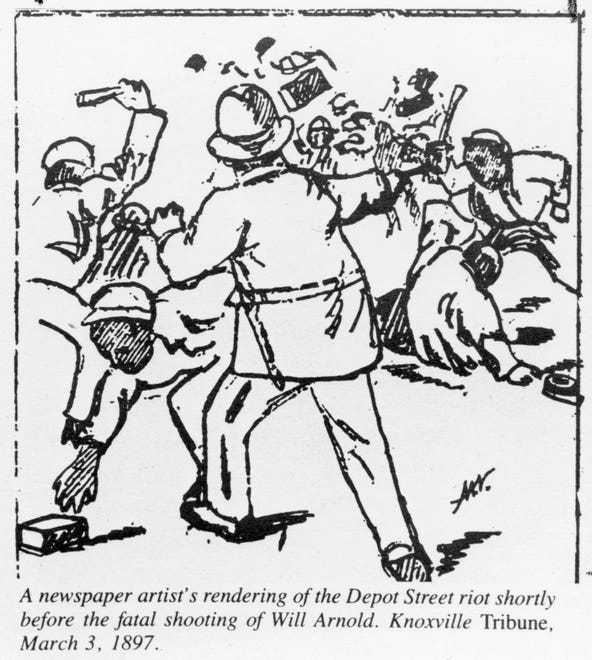

The “Battle of Depot Street” occurred on March 1, 1897, in Knoxville, Tennessee. City and county officials disputed the authority of the Citizens Railway Company. The company, led by McAdoo, wanted to build streetcar tracks along Depot Street, leading to a riot. The conflict escalated into a standoff between city police and county sheriff’s deputies. That resulted in the detention of key figures, including McAdoo and his opponent C.C. Howell. McAdoo and Howell struggled for two years to control Knoxville’s streetcar system. This incident was the climax of their struggle. Mob violence marked it, leading to one fatality (Will Arnold) and many injuries. Following the clash, McAdoo left Knoxville, and Howell consolidated the city’s streetcar lines. The dispute centered on control of the streetcar system. McAdoo’s company faced bankruptcy after a costly conversion to electric power. Howell’s syndicate had purchased most of the company’s assets. Yet, legal battles persisted between the two factions.

In 1901, McAdoo assumed leadership of a venture. The venture aimed to construct the Uptown Hudson Tubes, a set of railroad tunnels beneath the Hudson River. The tunnels would link Manhattan with New Jersey. A tunnel had been partially built in the 1880s by Dewitt Clinton Haskin. McAdoo served as the president of the Hudson and Manhattan Railroad Company. He oversaw the completion and opening of two passenger tubes in 1908. These tunnels are currently integral components of the PATH train system.

Subscribe to Frederick R. Smith Speaks

The Frederick R. Smith blog is the ramblings of an uncommon man in a post-modern world. As a master of few topics, your author desires to give readers a sense of the thoughts of a senior citizen who lived most of his life before the new normal.

Great piece... As a steam locomotive buff, I always enjoy posts about rail history. But it does make one wonder... can the government ever get anything done right?

Excellence! BRAVO