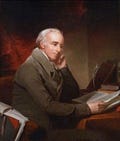

Dr. Benjamin Rush

Dr. Benjamin Rush was a prominent figure in American history, known for his contributions to medicine and politics. He was a vocal critic of slavery and supporter of women’s rights.

In contemplating the political institutions of the United States, I lament, that we waste so much time and money in punishing crimes, and take so little pains to prevent them. We profess to be republicans, and yet we neglect the only means of establishing and perpetuating our republican forms of government, that is, the universal education of our youth in the principles of Christianity, by means of the Bible; for this divine book, above all others, favors that equality among mankind, that respect for just laws, and all those sober and frugal virtues, which constitute the soul of republicanism

Dr. Benjamin Rush

Introduction

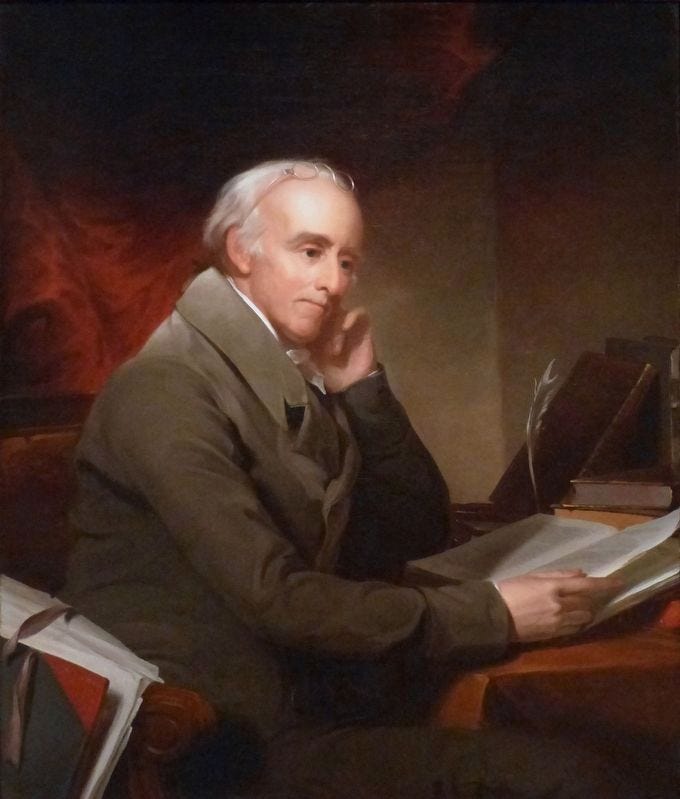

Dr. Benjamin Rush was a prominent figure in American history, known for his contributions to medicine and politics. Born on December 24, 1745, in Byberry, Pennsylvania, Dr. Rush was the fourth of seven children of John Rush and Susanna Hall Rush.1 His father was a farmer, while his mother was the daughter of a Quaker preacher.

His father died when he was just six years old. While his mother did her best to care for her family, young Benjamin was supervised by his uncle, Reverend Samuel Finley.

As a child, Dr. Rush relished science and medicine and often spent hours reading books on these subjects. He attended the College of New Jersey (now Princeton University) and graduated with a bachelor’s degree in 1760 at just fourteen. After completing his undergraduate studies, Dr. Rush pursued a medical career. He enrolled at the University of Edinburgh in Scotland.

While studying at Edinburgh, Dr. Rush became interested in the ideas of the Scottish Enlightenment. That movement emphasized reason, science, and progress. He also developed a strong interest in psychology and treating mental illness, a new field at the time.

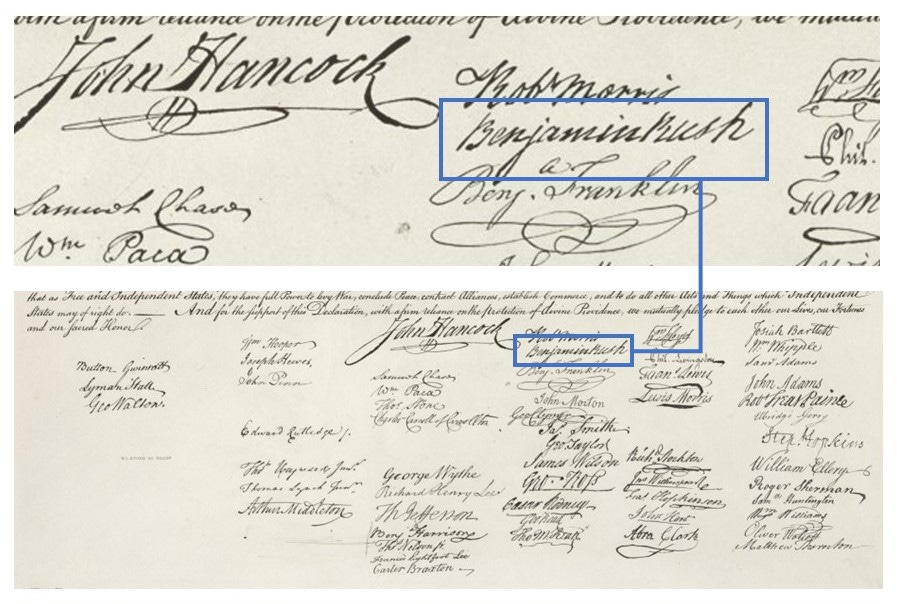

In 1768, Dr. Rush completed his medical training and traveled to London to practice at St. Thomas Hospital. There, he became friends with Benjamin Franklin. Through this connection, he became the first Professor of Chemistry at the College of Philadelphia (now the University of Pennsylvania). Returning to the Colonies in 1769, Dr. Rush became a prolific writer. He wrote many volumes of patriotic and medical essays. Dr. Rush wrote the first book on chemistry in America titled A Syllabus of a Course of Lectures on Chemistry. He signed the Declaration of Independence.

On January 11, 1776, Dr. Rush married Julia Stockton (1759–1848), daughter of Richard and Annis Boudinot Stockton. Richard Stockton also signed the Declaration of Independence. The Rush’s had 13 children, nine of whom survived their first year. The children included John, Ann Emily, Richard, Susannah (died as an infant), Elizabeth Graeme (died as an infant), Mary B, James, William (died as an infant), Benjamin (died as an infant), Richard, Julia, Samuel, and William. Richard later became a member of the cabinets of James Madison, James Monroe, John Quincy Adams, Andrew Jackson, James K. Polk, and Zachary Taylor (at one point during their presidencies).

Dr. Rush established a successful medical practice and gained a reputation as one of the leading doctors in the City. Besides his work as a doctor and professor, Dr. Rush actively participated in politics. He was a member of the Continental Congress and served as the Treasurer of the United States Mint under the Presidency of George Washington. Dr. Rush became a member of the Sons of Liberty and represented Pennsylvania in the Continental Congress.

Dr. Rush was prominent in the Continental Army during the American Revolutionary War. In a pacifist role in line with the precepts of his upbringing, Dr. Rush served as a Continental Army surgeon. He was appointed the Middle Department’s chief medical officer, covering Maryland, Pennsylvania, and Delaware. In this role, he was responsible for the medical care of the soldiers in the region and for procuring and distributing medical supplies.

Dr. Rush was present at the Battle of Trenton (December 26, 1776), where he cared for the wounded and dying on both sides of the conflict. In addition to his medical duties, Dr. Rush played a crucial role in planning the Battle of Trenton. He was a close confidant of George Washington and provided valuable insights and advice on the strategy and tactics of the battle. He also served at the Battle of Princeton (January 3, 1777).

Abolitionist

Christianity and Quakers shaped Dr. Rush’s political views and belief in justice for ordinary people. He was a vocal critic of slavery and played a vital role in the abolitionist movement. He was also a strong supporter of women’s rights and was one of the first proponents of women’s education.

Despite his advanced views and commitment to parity, Dr. Rush enslaved William Grubber, who he purchased in 1775 or 1776. At the time, slavery was an accepted and widely practiced institution in the United States, and many of the Founders, including Dr. Rush, enslaved people. However, as he matured and his views on slavery evolved, Dr. Rush came to regret this decision and began to advocate for the abolition of slavery actively. Dr. Rush freed Grubber on February 25, 1794, who died five years later.

In 1787, Dr. Rush wrote an essay titled An Inquiry into the Effects of Public Punishments upon Criminals and upon Society, in which he argued that slavery was a form of cruel and unusual punishment that was not only morally wrong but also detrimental to Society. He argued that the institution of slavery promoted a culture of violence and oppression and that it was a corrupting influence on both enslavers and enslaved people.

Despite his efforts, slavery remained a contentious issue in the United States for many years. It was not until the 13th Amendment to the Constitution, ratified in 1865, that slavery was finally abolished.

While it is easy to look back at history with the benefit of hindsight and criticize individuals like Dr. Rush for their participation in the institution of slavery, it is essential to recognize that they were products of their time. Their views and actions should be evaluated in the context of the Society in which they lived. Nevertheless, Dr. Rush’s regret and efforts to address the issue of slavery demonstrate his willingness to confront and correct his own mistakes. His legacy is an essential reminder of the need to strive for progress and justice. Furthermore, nothing in source documents indicates Dr. Rush physically tormented William Grubber. Dr. Rush’s writings suggest that he looked after the well-being of Grubber.

Dr. Rush’s anti-slavery leanings became apparent after 1769, following a meeting with influential Quaker abolitionist Anthony Benezet, a vocal critic of the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade. Dr. Rush became an open admirer of Benezet, later writing that his “name is held in veneration in these parts and deserves to be spread throughout the world.”

Dr. Rush was a member of the Pennsylvania Society for Promoting the Abolition of Slavery. He helped to re-establish that organization as the Pennsylvania Abolition Society. As an abolitionist, Dr. Rush believed slavery was a moral evil and worked to end the practice in the United States. He argued that slavery violated the natural rights of individuals. Dr. Rush thought everyone had the same freedoms and privileges, regardless of race.

Besides his activism, Dr. Rush used his prominent doctor and medical community member position to speak out against slavery. He argued that slavery harmed enslaved people’s physical and mental health. Dr. Rush advocated for more humane treatment of enslaved individuals.

Despite his efforts, Dr. Rush faced significant opposition to his views on slavery. Many of his contemporaries held pro-slavery views and opposed his efforts to end the practice. Yet, Dr. Rush remained committed to his beliefs and spoke out against slavery throughout his career.

Medical and Social

Dr. Rush’s most significant contribution to medicine was his work on “nerve energy.” He believed that the body self-regulated through a system of nerves that carried energy from the brain to the various organs and tissues. This idea was revolutionary at the time and helped to pave the way for our modern understanding of the nervous system. Dr. Rush was one of the first people to describe Savant Syndrome. In 1789, he wrote about the abilities of Thomas Fuller, an enslaved African who was a “lightning calculator.”

Dr. Rush was also a pioneer in the treatment of mental illness. He believed mental illness resulted from an imbalance in the body’s nervous system. Dr. Rush advocated for “moral therapy,” which involved treating patients with kindness and respect. He bemoaned harsh methods such as punishment and restraints.

Despite his many achievements, Dr. Rush was not without controversy. He supported bloodletting. As a common medical practice, it involved removing blood from a patient to cure various ailments. His contemporaries and later medical professionals criticized bloodletting as ineffective and harmful.

Despite this, Dr. Rush remained respected and influential in the medical community. He was the first president of the Philadelphia College of Medicine. Dr. Rush was also instrumental in establishing the first free clinic in the United States, which provided medical care to the poor. He was a founding member of the American Philosophical Society.

Besides his work in medicine, Dr. Rush advocated various social and political causes. He was a strong supporter of education and helped to establish the first public school in Philadelphia. Dr. Rush was also an advocate for prison reform. He worked to improve prison conditions, which were often overcrowded and unsanitary at the time.

Dr. Rush deplored public punishments such as putting a person on display in stocks (common at the time). Instead, he proposed private confinement, labor, solitude, and religious instruction for criminals and opposed the death penalty. His outspoken opposition to capital punishment pushed the Pennsylvania legislature to abolish the death penalty for all crimes other than first-degree murder. He authored a 1792 treatise on punishing murder by death. He made three principal arguments:

Every man possesses absolute power over his liberty and property, but not over his own life...

The punishment of murder by death, is contrary to reason, and the order and happiness of Society...

The punishment of murder by death, is contrary to divine revelation.

Conway Cabal

Dr. Rush was involved in several significant events and controversies during his career. The most notable was the Conway Cabal, a political intrigue during the American Revolution.

The Conway Cabal was a plot by politicians and military leaders to remove George Washington. The plan - replace Washington (commander in chief) with Major General Horatio Gates. Brigadier General Thomas Conway led the conspiracy. Continental Congress appointed Conway as an inspector general of the Continental Army.

Dr. Rush had volunteered in 1775 for service in the Army, and on April 11 11, 1777, he became Surgeon General of the Middle Department. Not finding the medical service administration to his liking, he charged Dr. William Shippen Jr. with inefficiency, but a Congressional investigation upheld Shippen. Because of that outcome, Dr. Rush felt that Washington’s handling of military matters was unsatisfactory.

After that, Dr. Rush got involved in the Conway Cabal through his friendship with Thomas Conway. They had been classmates at the College of New Jersey (now Princeton University). Conway wrote Dr. Rush a letter expressing his dissatisfaction with Washington’s leadership. Conway sought Dr. Rush’s support in the plot to replace Washington. Dr. Rush wrote Patrick Henry anonymously from Yorktown on January 12, 1778, to recommend that Horatio Gates or Thomas Conway replace Washington. Governor Patrick Henry forwarded the letter to Washington. The Commander in Chief recognized Dr. Rush’s excellent penmanship and confronted him with this evidence of personal disloyalty.

The exposure of the Conway Cabal had significant consequences for those involved. Conway faced removal from his position as inspector general and left the Continental Army. Dr. Rush paid a heavy price for his indiscreet letter to Patrick Henry. Rush resigned from the Army on April 30, 1778.

Having served in Colonel John Cadwalader’s regiment at the Battle of Trenton (1776), the Conway Cabal was an embarrassment for Dr. Rush, particularly on July 4, 1778. On that second birthday of the nation, Cadwalader, loyal to General Washington, fought a duel with Conway. He shot him in the mouth, but Conway recovered from the injury.

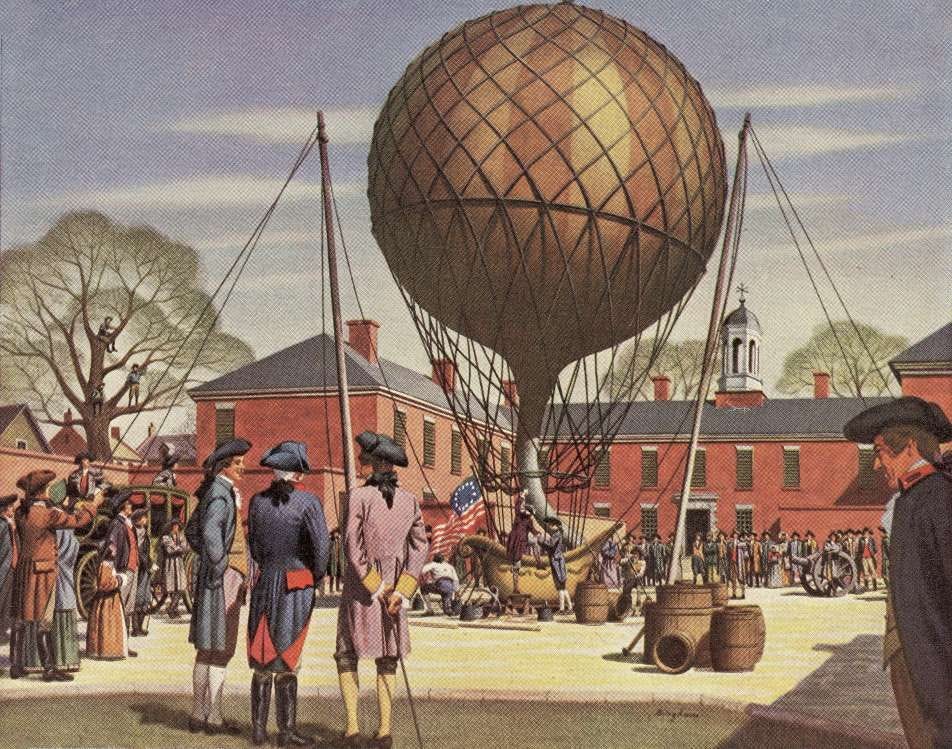

First Flight

On January 9, 1793, Jean-Pierre-François Blanchard launched his hydrogen-filled balloon in Philadelphia. There, Blanchard staged his balloon in the courtyard of the Walnut Street Prison.

The prison courtyard was essential to ensure the first successful manned flight. The walls protected the balloon and a hydrogen-making “ventilator” from curiosity seekers. That operation included pouring large quantities of water diluted sulphuric acid and water into a barrel of iron filings—tubes and valves to control the resulting gas outflow.

Dr. Rush assisted Blanchard with the preparations for his flight. Other scientists who helped included Dr. Casper Wistar, Peter Legaux, Dr. David Nassy, and Benjamin Franklin Bache. At the time, Dr. Rush was a Professor at the Institutes of Medicine and Clinical Cases at the University of Pennsylvania. He also instructed Blanchard on how to conduct an in-flight medical experiment.

Challenges

Despite his many achievements, Dr. Rrush encountered many challenges and setbacks throughout his life. In 1793, he was one of the doctors who treated the victims of the yellow fever outbreak in Philadelphia. He also faced several legal and financial disputes, which affected his health and reputation. Despite this, Dr. Rush remained respected and influential in the medical community. He died suddenly in his home on April 19, 1813, at 67.

Review

Today, we remember Dr. Rush as a medicine, psychology, and abolitionist movement pioneer. He made significant contributions to understanding the nervous system and treating mental illness. His work and ideas continue to influence modern medical practices. Dr. Rush’s legacy lives on as a respected and influential figure in American histoy.

Reflection

Dr. Rush’s birthplace, Byberry, Pennsylvania, has a rich history dating back to the late 17th century. The area was initially settled by the Byberry Quakers, who established a meeting house and farmsteads in the region. In the 19th century, Byberry became a popular summer retreat for Philadelphia’s wealthy elite, who built large mansions and estates. Originally it was incorporated as the Township of Byberry and was the northeasternmost municipality of Philadelphia County before the City and County were consolidated in 1854.

The pioneering work by Dr. Rush work in mental health is an ironic link to the future. One of the most notable landmarks in Byberry is the Byberry Mental Hospital, established in 1906. The hospital was initially designed to provide care for the mentally ill, but it gained a reputation for poor conditions and abuse of patients. It was eventually shut down in 1990 and has since been converted into a residential community.

Before the Byberry Mental Hospital’s 1990 closure, in the 1970s, my father, an electrical business owner, had contracts with the facility to perform electrical construction work. As a teenager, I often accompanied my father to learn about the business. That activity gave me the opportunity at an early age to experience the bizarre world of “insane asylums.” Such an experience was one of the many things that instilled a desire to enjoy history and learn about the beginnings of many types of institutions and human endeavors.

Working “in the footsteps” of Dr. Rush was a natural progression from my walks to grade school on the sidewalk of a street named after a local Revolutionary War hero, Colonel John Cadwalader. As reviewed above, Dr. Rush served in the same regiment as Cadwalader in the Trenton-Princeton Campaign (1776-1777) and assisted with North America's first manned balloon flight (1793). To this day, my friend Stephen R Moylan, a descendant of Stephen Moylan, aide-de-camp to George Washington, continues the legacy of the first North American balloon flight. Dr. Rush aided with the preparation of the balloon flight. To my delight, it all has come full circle.

Afterword

Historians often use the word “progressive” to describe Dr. Rush’s innovative social work. Hacked by the collective, “progressive” implies “good intentions.” Some government policies, enacted with benevolence, fail or produce opposite results from the lawmakers’ good intentions. But it is worse today, with the modern collective (progressive) hive canceling individualism and replacing it with the worship of corporatocracy. Dr. Rush’s good work is nothing like the progressive WOKE alt-reality of today. 📕

Sources and Recommended Reading

Benjamin Rush: Patriot and Physician ~ Alyn Brodsky ~ 417 pages ~ Truman Talley Books ~ December 2013

Washington’s Crossing ~ David Hackett Fischer ~ 564 pages ~ Oxford University Press ~ February 2004

Encyclopedia of the American Revolution ~ Mark M. Boatner ~ 1312 pages ~ Stackpole Books ~ August 1994

John Adams ~ David McCullough ~ 752 pages ~ Simon & Schuster ~ September 2002

The Sin of Slavery ~ Frederick R. Smith ~ September 25, 2020

First Flight 1793 and the Finest Part 2 - First Launch ~ Frederick R. Smith ~ July 9, 2022

Originally, Byberry was incorporated as the Township of Byberry and was the northeasternmost municipality of Philadelphia County before the City and County were consolidated in 1854. It is now part of the City’s “Great Northeast” section.

Great article. However, the 13th amendment did not free the slaves. Anyway, I don't read it that way. The 13th amendment nationalize slavery for crime and it was never ratified. It is still not the law of the land even today. Crime became rampant in the US after 1865 along with even worse slavery than before. https://www.ancestry.com/historicalinsights/prison-life-united-states-after-civil-war

"Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction."

We get a partial answer, 9mm was legally bought by the boy's mom, and not stored properly.

https://www.newsbreak.com/news/2884631847080/teacher-shot-by-six-year-old-student-was-trying-to-take-the-gun-away-from-him?_f=app_share&s=a99&share_destination_id=MTcyODI5MjA3LTE2NzMzNjMxMDU0OTg=&pd=0BhAlruD&hl=en_US&send_time=1673363105&actBtn=floatShareButton&trans_data=%7B%22platform%22%3A1%2C%22cv%22%3A%2222.52.0%22%2C%22languages%22%3A%22en%22%7D

I'M A Legal CARRIER AND HAVE BEEN SINCE 1997, I LEARNED THE RULES, AND FOLLOW THEM. I'm a grandma, so I have a gun safe when not in use, when I carry it's on my hip, not my purse. Never leave it unwatched unless it's in the gun safe. And my granddaughter was taught Never to touch it, I smack hands or butt. Easier to do the safe things, kids forget.