Discover more from Frederick R. Smith Speaks

John Henry the Steel-drivin’ Man

John Henry, also known as Jawn Henry, is a legendary figure in American folklore, celebrated for his remarkable strength and endurance.

Nelson, Scott Reynolds. Steel Drivin’ Man: John Henry, The Untold Story of an American Legend (p. 87). Oxford University Press.

Words: 15,009 ~ Read time: 10 min

Foreword

In schools, especially academia, hostility arises with demands for “political correctness” under the caustic “equity” banner. Society lacks truth and respect, embracing indifference to facts. In 2020-2021, deliberate lies spread through new communication methods. This trend reflects a more considerable disregard for honesty in society.

Nevertheless, visiting historical sites alters the course of research and influences the approach and execution in numerous ways. Furthermore, it significantly impacts the teaching and comprehension of history. With so many under the equity spell, it is readily observable how cogent-thinking students, who have experienced visits to historical locations during their formative years, stand out. Their enhanced historical imagination, grasp of history as tangible events, and awareness of its relevance across different historical epochs are evident distinctions. That is as uncommon today as mainstream-installed Marxism promotes the canceling of historical statues. The inane canceling includes the very icons of the past who fought the cause to free the enslaved people.

A lifelong “boots on the ground” contact with the long echoes of the past and my adult career in rail transportation helped me grasp history unencumbered by today’s collective ignorance. With this installment of rail history, join me in retracing my footsteps along the Chesapeake & Ohio Railway in Virginia and West Virginia. Some years ago, in my official capacity, I walked and rode the rails over the ground that once stood a towering power of history: John Henry.1

Introduction

John Henry, also known as Jawn Henry, is a legendary figure in American folklore, celebrated for his remarkable strength and endurance. His tale revolves around a legendary battle against a steam-powered drilling machine during the construction of railroad tunnels, with the Big Bend Tunnel in Talcott, West Virginia, often cited as the setting. However, conflicting sources suggest origins in Mississippi and Alabama within the late 19th-century railroad construction boom. Despite the myth and debate surrounding his life, recent research has uncovered elements of truth, situating John Henry as an actual figure involved in tunnel construction in Virginia. His story has transcended generations, symbolizing the struggles and resilience of the American working class against the encroachment of technology. This essay explores the enduring legacy of John Henry, examining his cultural significance, the appropriation of his narrative by various movements, and even his namesake in an experimental steam turbine locomotive, cementing his place in American history and folklore.

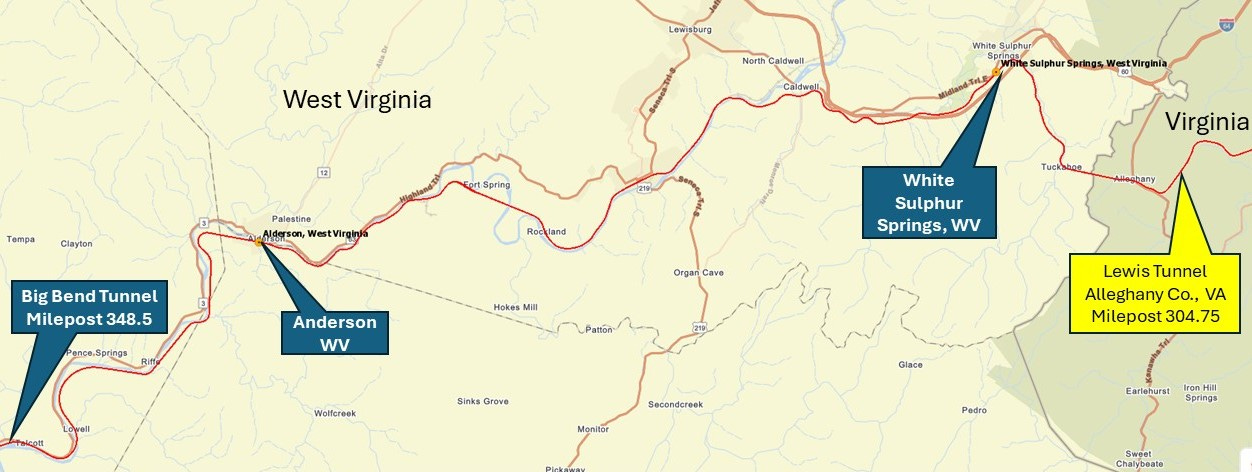

John Henry

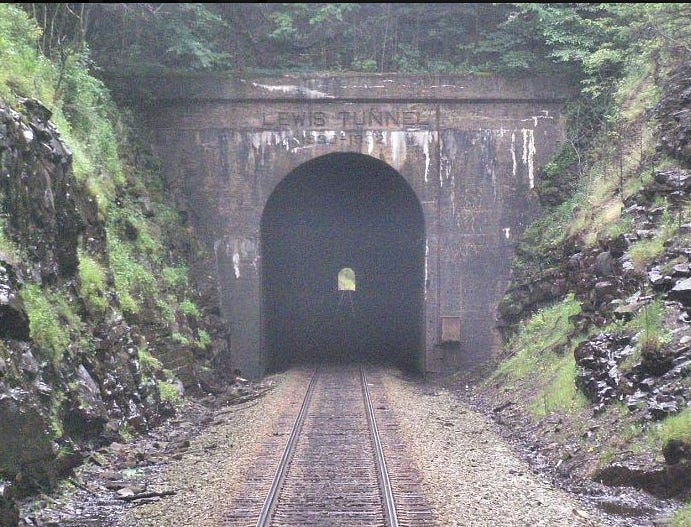

John Henry is a legendary African American figure in American folklore. He celebrates his strength and endurance. He is also known for his battle against the steam-powered drilling machine. That happened during railroad tunnel construction. Many sources suggest the Big Bend Tunnel near Talcott, West Virginia.2 Some sources say that the story of John Henry comes from Mississippi and Alabama.3 That is within the context of the building of railroads in the late 19th century. But, as we will see later, more recent research found Henry to be more than a legend. He worked on the Lewis Tunnel in Virginia.

Myth and debate shroud the details of John Henry’s life. But his story has become a crucial part of American culture. It symbolizes the struggles of the working class against the encroachment of technology.

The legend of John Henry began in the late 19th century, at the peak of the Industrial Revolution in the United States. John Henry was an African American railroad worker who was crucial in building the nation’s growing rail network. These workers faced harsh conditions, long hours, and dangerous work, but they were essential in building the country’s infrastructure.

John Henry became a “steel-drivin’ man.” He swung a heavy hammer at a steel drill, driving it into rock. This process made railway tunnels through hills and mountains. Railroads spread across the United States after the Civil War. In another version of his story, John Henry was born into slavery. The Emancipation Proclamation freed him. His wife had their chains forged into a 20-pound hammer, which he used to join railroad workers. If they finished building the railroad line, they promised them land.

According to many ballads that made him famous, John Henry battled a steam-powered drill, beat the machine, and died “with his hammer in his hand.” In some versions of the story, John Henry survives but is later killed in a tunnel collapse or dies from the strain on his body. Regardless of the details, John Henry beat the steam drill. His victory became a symbol. It stood for human toughness and the enduring spirit of the American working class.

Folklorists thought John Henry to be mythical. But, historian Scott Nelson discovered that he was real. He was a nineteen-year-old from New Jersey. A Virginia court convicted him of theft in 1866. He received a ten-year sentence in prison and was tasked with building the Chesapeake and Ohio Railway (C&O). Henry and other prisoners worked with steam drills in 1870 at the Lewis Tunnel east of White Sulphur Springs, WV, in Virginia.4

Nelson’s research in his book Steel Drivin’ Man: John Henry, The Untold Story of an American Legend pieces together the biography of John Henry. His story is also one of many work songs. The songs made Henry into a folk hero. They also served as tools of resistance and protest, reminding workers to slow down or face dire consequences.

John Henry’s legacy endures through ballads and work songs. These ballads keep his story and those of other African American railroad workers alive. They gave their lives in these dangerous jobs. There are nearly two hundred documented renditions of John Henry’s ballad. This song is among the earliest blues and one of the first country songs recorded. Folklorists associated with the Library of Congress regard it as the most extensively studied folk song in the United States.

They took John Henry to the white house,

And buried him in the san’

And every locomotive come roarin’ by,

Says there lays that steel drivin’ man,

Says there lays that steel drivin’ man.

The “white house” in the ballad is a building constructed in 1825 at the Richmond, Virginia State Penitentiary.5 The penitentiary used the area at the white house as a burial ground for prisoners who passed, such as John Henry. The line “And every locomotive come roarin’ by” refers to trains passing the penitentiary on the nearby Richmond Fredericksburg & Potomac Railroad (FF&P).6 The penitentiary shut its doors in 1990, and the adjacent section of the RF&P line has also long vanished. However, CSXT owns the RF&P remnants. The C&O is now a part of CSXT, and today, its trains roll by on a nearby rail line, echoing the ballads of John Henry.

The narrative and ballads endure. It says a man’s worth is only in his strength. Machines challenge him. It has lasted a century despite its historical inaccuracy. John Henry’s poignant assertion to the work “captain,” “A man ain’t nothing but a man,” resonates. It reminds us of the countless unnamed laborers. They contributed to America’s development through their toil, many paying with their lives. John Henry’s victory over the steam drill symbolized human resilience. It showed the enduring spirit of the American working class. He symbolizes their sweat and hard work as they built and maintained rails across the Appalachian mountains. His tale is a lasting reminder of human resilience. It is also a reminder of resistance against technological encroachment and abuses.

The Cultural Appropriation of John Henry

Various movements and ideologies have appropriated John Henry’s story over time. The communist movement made a notable appropriation. They found in John Henry a potent symbol for their narrative. It was about labor rights, solidarity, and resistance to capitalist exploitation.

Communism emerged as a significant political force in the 19th and 20th centuries. It advocated ending private property and class equality and aimed to create a classless society. Communism gained traction in the United States during times of social upheaval, including the Great Depression and the early 20th-century labor movements. During these times, John Henry’s figure became intertwined with the struggles of the working class.

The communist movement seized John Henry’s symbolism to galvanize support for its cause. They found John Henry in the story. He epitomized the plight of the proletariat (wage earners). They saw him as pitted against the machines of capitalist production. His defiance and ultimate sacrifice became a rallying cry for workers’ rights and collective action.

The appropriation of John Henry by the communist movement was not without controversy. Some critics argue that the movement oversimplified and romanticized the story of John Henry. They reduced it to a straightforward allegory for class struggle. Others contend that the communist movement co-opted a distinctly American folk hero. They did this to align with the values and aspirations of the American working class. Critics see right through this appropriation. Yet, the communist movement’s use of the John Henry icon made it more culturally resonant and appealing. Communists invoked the spirit of John Henry. They tapped into a deep well of cultural memory and collective identity. They harnessed it to advance their political agenda.

…many more Americans besides Charles Seeger began to believe that radical political change was required to bring the nation back to full employment. Those in the Communist Party believed that this change had to start with a workers’ movement. Seeger and the Workers Music League became convinced that, properly edited, folk songs like “John Henry” could form the basis for a truly proletarian music that would help mobilize those men and women. Abandoning classical musical forms, he and other socialists and Communists in New York eventually embraced the story and song of John Henry. While for [Carl] Sandburg, and presumably [Thomas Hart] Benton, the ballad of John Henry had represented workers’ travails against the modern age and capitalism, Workers Music League members like Charles Seeger heard the song in very different registers. For them, the song represented more than just a challenge to modern capitalism. The ballad seemed to echo the key conflict in workers’ lives that Karl Marx had identified: the intensification of work that came with the introduction of machinery. The song also seemed to speak out about the problems of Jim Crow, convict labor, and racism in the South.7

The heyday of the communist movement in the United States has passed. But, the legacy of its appropriation of the John Henry icon endures. John Henry remains a symbol of resistance and collectivist unity. He inspired later activists and labor organizers. This same collectivist movement charges on with their ongoing “struggles.” The collectivist “justice” narrative now occurs under the banner of diversity-equity-inclusion. Big-money influencers refer to it as Environmental, Social, and Corporate Governance. It is all under the crony capitalism or “corporate communism” rubric.

Jawn Henry the Locomotive

Baldwin Lima Hamilton Locomotive Works (BLH) in Pennsylvania worked with Babcock & Wilcox. They built a 4,500-horsepower steam turbine electric engine for freight service on the Norfolk & Western Railway (N&W). The name Jawn Henry was a natural fit.8 It epitomized the powerful rock driller who tried to prove that a man could work faster than a steam drill.

No. 2300, the Jawn Henry, was a single experimental steam turbine locomotive. Assembled in May 1954, two years before BLW quit locomotive building, the N&W placed it in their TE class (locomotive type designation). Designed to prove the advantages of steam turbines, it weighed in at 818,000 pounds. Baldwin Chief Engineer Ralph P. Johnson supported this idea. It delivered up to 4,500 horsepower.

The Jawn Henry had four six-axle wheel assemblies (trucks) identified by railroads as a C+C-C+C arrangement. It has a Babcock & Wilcox water-tube boiler with automatic controls. The boiler controls proved problematic. N&W retired No. 2300, the Jawn Henry, and it was stricken from their roster on January 4, 1958, and scrapped later in 1957.

The Jawn Henry was similar to the three turbines built by BLW for the Chesapeake and Ohio between 1947 and 1948 but differed mechanically. The C&O locomotes (No. 500-503) were heavier than the Jawn Henry at 856,000 pounds. At 106 long plus a tender, it delivered up to 6,000 horsepower. As with the Jawn Henry, coal dust and water entered the electric traction motors. The C&O’s steam turbine 500s outweighed the N&W’s Jawn Henry. Jawn Henry also outweighed the Union Pacific Big Boy (772,000 pounds). Oddly, N&W chose Jawn Henry for its experimental locomotive, not the legendary steel-driving man’s home road, the C&O.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the enduring legacy of John Henry, whether as a folk hero or a historical figure, underscores his profound significance in American culture. Through retelling his tale, John Henry has become more than just a symbol of physical strength; he embodies the indomitable spirit of the American working class and their ongoing struggle against the forces of industrialization and technological advancement. Despite the ambiguity surrounding his origins and the debates over his authenticity, John Henry’s story continues to resonate across generations, inspiring social justice and labor rights movements. Whether through ballads, work songs, or even the appropriation of his narrative by various ideological activities, John Henry remains a powerful emblem of resilience and defiance. His name lives on in folklore and the annals of American history, reminding us of the enduring human spirit in the face of adversity.

Afterword

Stay tuned, my friends, as we continue the history of the past with Fred’s boots on the ground. This time, it will include my dirty hands and a sore back starting in the early 1970s. We explore the ballad of the Gandy Dancers.

Parting Handshake

For a recent visit to a C&O Railway landmark near John Henry’s footsteps, behold my March 2023 visit to the Greenbrier in White Sulpher Springs, West Virginia. 📕

Sources

Fred Smith Libray Books

The Locomotives Baldwin Built ~ Fred Westing, 192 pages, Bonanza Books, 1966

Guide to North America Steam Locomotives ~ George H. Drury, 335 pages, Kalmbach Books ~ 2015

Steel Drivin’ Man: John Henry, The Untold Story of an American Legend ~ Scott Reynolds Wilson, 224 pages, Oxford University Press, September 2006

Online

C&O Lewis Tunnel ~ Wikimapia

Beast of the East ~ Frederick R. Smith Speaks

John Henry ~ Library of Congress

C&O Alleghany, Lewis, Kelly, Lake and Moore Tunnels ~ industrialscenery.blogspot.com

I warmly encourage you to consider becoming a paid subscriber if you have the means. Tips are appreciated, too. Regardless of your choice, your support is deeply appreciated. From the bottom of my heart, thank you for your invaluable support!

These walks were officially sanctioned and under safety protocols. Never walk a railroad track outside these parameters.

The builder of the Big Bend Tunnel (constructed 1870-72) never used steam drills. Captain William R. Johnson Jr., who used primarily free workers to build his tunnel, was the contractor in charge of the Big Bend. However, he took thirty Virginia prisoners from Wardwell in 1868 and another fourteen in 1869. Nelson, Scott Reynolds. Steel Drivin’ Man: John Henry, The Untold Story of an American Legend (p. 81). Oxford University Press. Kindle Edition.

The original tunnel was built between 1870-73. Over time, C&O built a second tunnel at Talcot next to the original bore. The development of Centralized Traffic Control (CTC) on the C&O mainline in the 1950s led to the centralization of traffic control. CTC, consisting of electronic switches or interlockings, is designed so conflicting train movements cannot be authorized. A train dispatcher could remotely control signals and powered switches. CTC allowed the C&O to have greater operating and cost efficiencies in operating trains over single tracks with lengthy sidings versus maintaining double-track setups. In 1974, C&O single-tracked the mainline near Talcott and abandoned the original Big Bend Tunnel.

Today, visitors are welcome to visit the site of the decommissioned tunnel. There, the public can view historical markers and a statue rendition of John Henry.

Chasing John Henry in Alabama and Mississippi ~ ibiblio.org

… records revealed how convicts and steam drills, working side by side, cut through not the Big Bend Tunnel but the Lewis TunnelLewis Tunnel. Nelson, Scott Reynolds. Steel Drivin’ Man: John Henry, The Untold Story of an American Legend (p. 39). Oxford University Press. Kindle Edition.

Located 45 miles east of the Big Bend Tunnel, the original Lewis Tunnel, a two-track bore, was completed in 1870. A second bore was built in 1931-32 with the original bore single-tracked.

Steel Drivin’ Man: John Henry, The Untold Story of an American Legend ~ Scott Reynolds Wilson, p. 34

Ibid., p. 38

From the site Historical Marker Database:

The Virginia General Assembly authorized a state penitentiary in 1796 during a penal reform movement aimed at rehabilitating convicts through confinement and labor. Benjamin H. Latrobe, who later designed the United States Capitol, was the primary architect. The penitentiary opened here in 1800, and other buildings were added later. Early inmates included former U.S. Vice President Aaron Burr, incarcerated in 1807 while awaiting trial for treason, and British prisoners captured during the War of 1812. Virginia’s executions took place here from 1908 until the penitentiary closed in 1990. Latrobe’s structure was razed in 1927, and the rest of the complex was demolished in 1992.

Steel Drivin’ Man: John Henry, The Untold Story of an American Legend ~ Scott Reynolds Wilson, p. 146

A steam turbine locomotive is a steam-powered unit that utilizes a steam turbine as its prime mover instead of traditional steam cylinders or pistons. Unlike conventional steam locomotives, which rely on reciprocating motion to drive the wheels, steam turbine locomotives like the Joh Henry use high-pressure steam to power electric generators. The electricity powers the traction motors like diesel locomotives.

Subscribe to Frederick R. Smith Speaks

The Frederick R. Smith blog is the ramblings of an uncommon man in a post-modern world. As a master of few topics, your author desires to give readers a sense of the thoughts of a senior citizen who lived most of his life before the new normal.

Fantastical historical summary and analysis - remember reciting the song as a kid and feelings its inspirational qualities as you mention. Always assumed that it was based on a true incident but never knew the details that you have assembled. Heroes can be very important examples and inspiration for children. Too bad that so many on the left want to rewrite history and trsr them all down. Thanks 👍👍👍

Good read, and brings back the songs of the time. Excellent as usual.