Discover more from Frederick R. Smith Speaks

USA Flag - Part 1, Our Heritage

This essay reviews the stream of shapes and colors that weave the pattern of our early history.

We take the stars from heaven, the red from our mother country, separating it by white stripes, thus showing that we have separated from her, and the white stripes shall go down to posterity, representing our liberty.

George Washington

Foreword

It is a joy to present this short journey into vexillology (historical study of symbolism and usage of flags). Vexillology synthesizes the Latin word vexillum, which refers to a kind of square flag carried by Roman cavalry, and the Greek suffix - logia (study). The first known use of vexillology occurred in 1959.

This post is about the flags of the North American Colonies and the early United States. Stay tuned for Part 2, an essay about the famous person most often associated with our flag, Betsy Ross.

Introduction

On June 14, 1777, the 2nd Continental Congress passed an act establishing an official flag for the new nation. The resolution stated: “Resolved, that the flag of the United States be thirteen stripes, alternate red and white; that the union be thirteen stars, white in a blue field, representing a new constellation.” On August 3, 1949, President Harry S. Truman declared June 14 as Flag Day.

The timeline of our United States flag and its precursors provides a fascinating window into the history of the Republic. It has inspired songs, survived battles, and developed in response to the nation’s growth. The red and white bars first appeared in 1765 (Son’s of Liberty). The first stars were in 1775 (Green Mountian Boys). Still, historians debate the precise origin of the first approved American flag (1777). Some believe New Jersey Congressman Francis Hopkinson made the design. Philadelphia seamstress Betsy Ross assembled it.

The Flags

The definition of a flag: is a usually rectangular piece of fabric of distinctive design used as a symbol (as of a nation), signaling device, or decoration.1 As shown below, our nation’s history includes remarkable periods and events signified by iconic symbolism. This compendium of flags illustrates the stream of shapes and colors that weave the pattern of our early history. Additional flags abound for readers so inclined. The sources at the bottom of this post are a good starting point for additional exploration.

According to custom and tradition, white signifies purity and innocence; red hardiness and valor; and blue represents vigilance, perseverance, and justice. The following list is a selection of the prominent flags from the early colonies up to 1821.

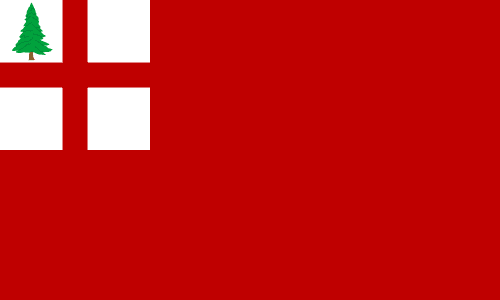

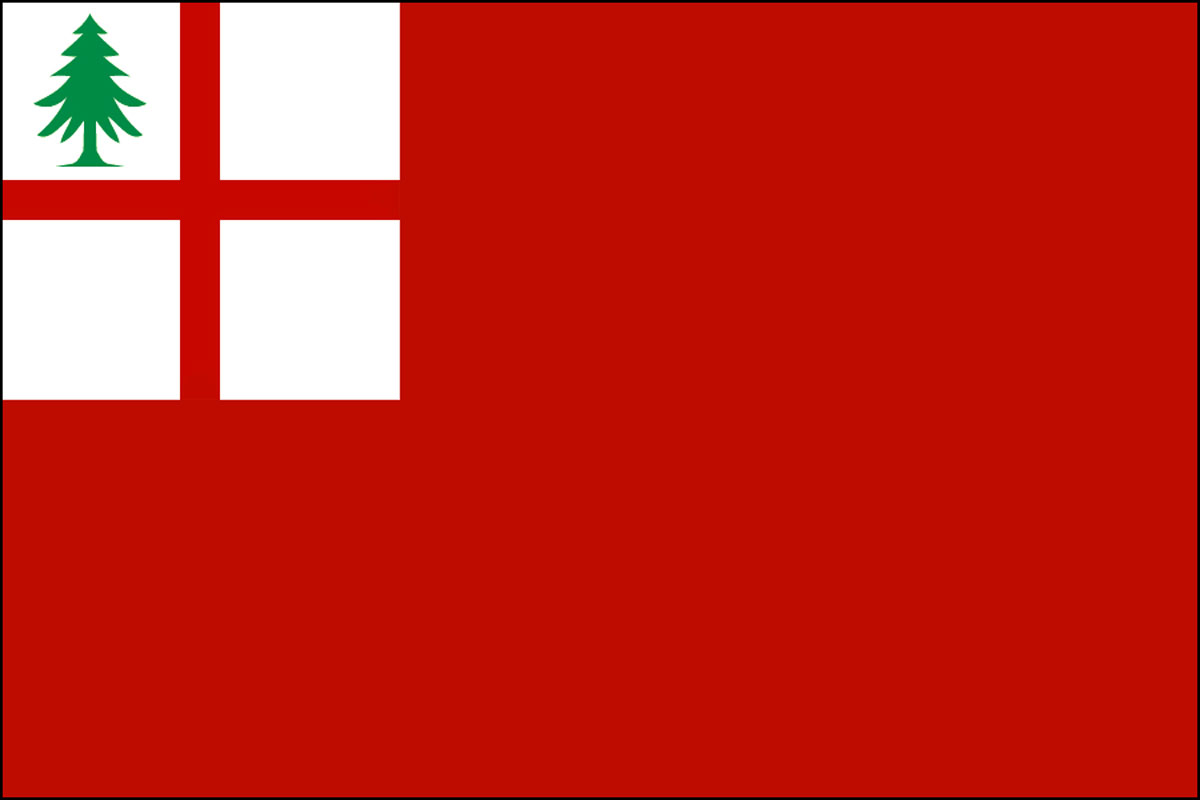

1686 New England Naval Ensign

The history of the pine tree as a symbol of New England predates the European colonial settlements. In eastern Massachusetts, southern New Hampshire, and the southern corner of Maine, there lived a nomadic tribe of Native Americans known as the Penacook. “Penacook” is an Algonquin word meaning “Children of the Pine Tree.” The colonists were starving to death during the winter of 1621-22. The Penacook people taught the Pilgrims of Plymouth Colony much-needed survival skills. A common way to customize English Red Ensigns for ships sailing out of New England included modification of the Cross of Saint George. It was the addition of a pine tree in the first quarter of the canton.

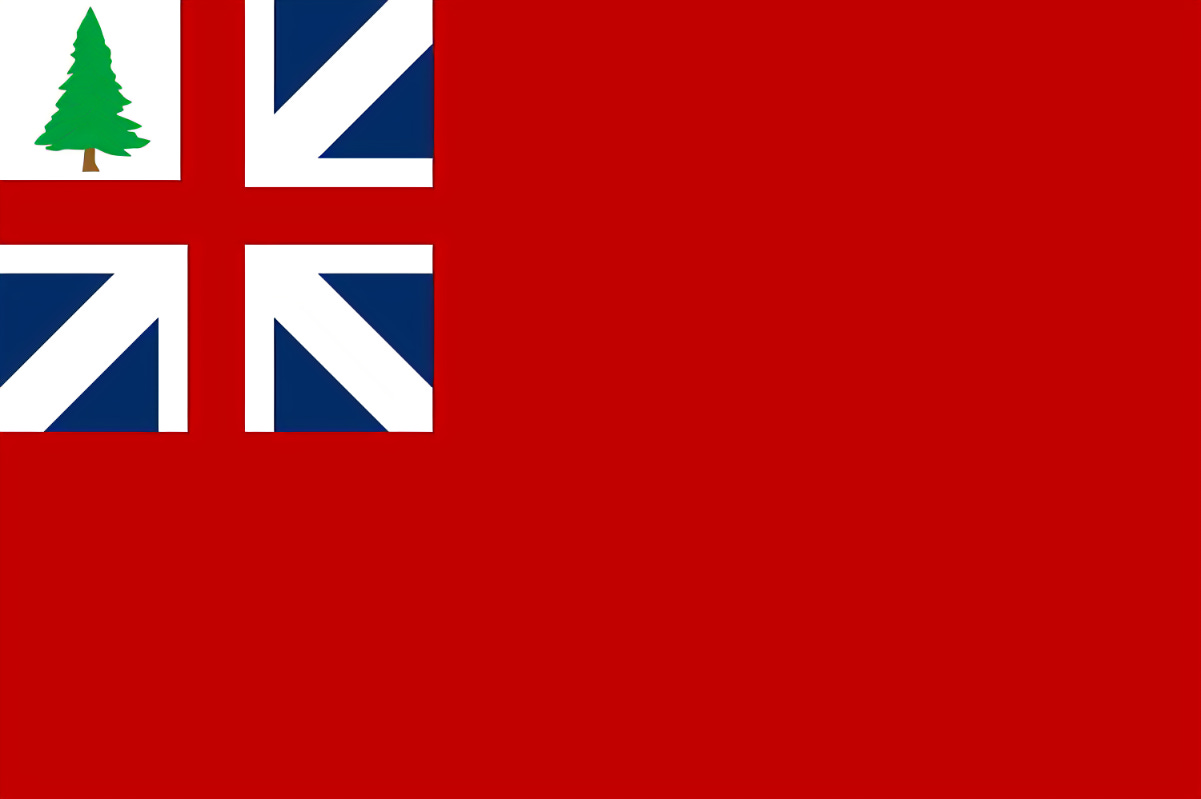

1707 New England Ensign

After the St. Andrews Cross was added to the St. George’s Cross to make the Union Flag in 1707, New England Flags sometimes showed the British Red Ensign with the tree in the first quarter.

1720 Bedford

Records show this the Bedford flag first appeared in 1720. It was at the Battle of Concord, Massachusetts, on April 19, 1775. Nathaniel Page, a Bedford, Massachusetts Minuteman, carried it. The Latin “Vince Aut Morire” means “Conquer or Die.” The arm emerging from the clouds represents the arm of God. Commissioning dating back to 1737 names Minuteman Nathaniel Page’s father John Page as “Cornett of the Troop of Horse.” That is the officer whose duty was to bear the unit’s flag. Nathaniel’s father, uncle, and grandfather are all mentioned within the Bedford and Billerica town records as “Cornet Page.” The documents state that Page could have carried a flag for the local militia troop as early as 1720. Bedford Town Library displays the flag as the “oldest existing flag” (of any type) in the country. A flag discovered in East Greenwich, Rhode Island, in 2022 could be as old as 1687 compared to Bedford’s early 1700s.2

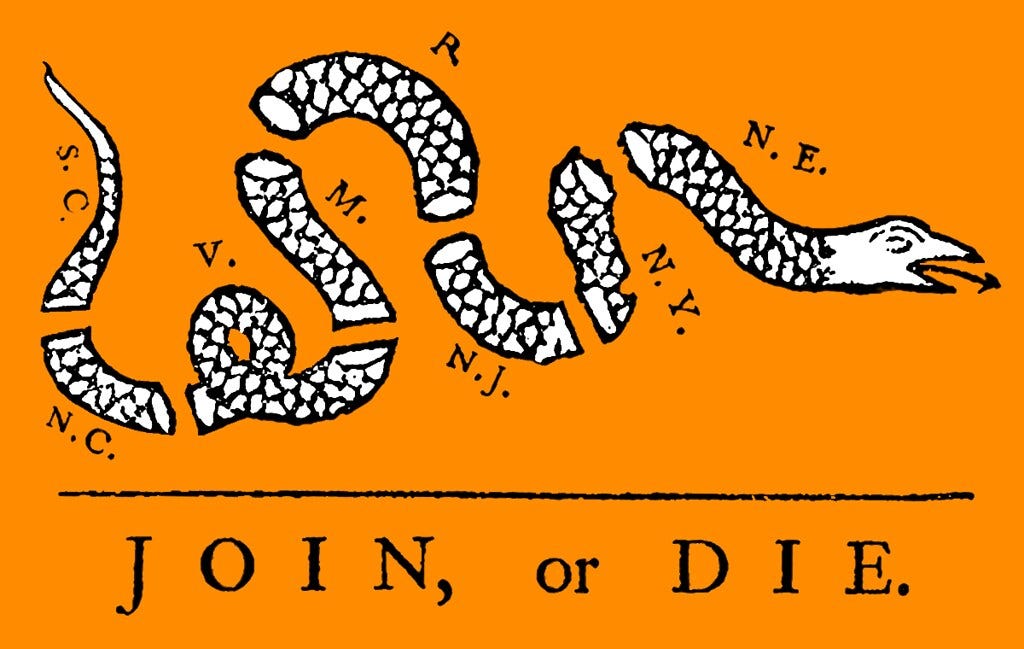

1754 Albany Congress

The rattlesnake was a favorite icon of the Americans even before the Revolution. In 1751 Benjamin Franklin, in his Pennsylvania Gazette, carried a bitter article. It protested the British sending its convicted criminals to America. The author suggested revenge by shipping a cargo of rattlesnakes to England. Upon arrival, distribute the snakes to the noblemen’s gardens. The drawing is a rattlesnake cut into segments, each labeled as one of the American colonies over the words “JOIN, or DIE.” Franklin argued for support of the Albany Plan and Congress that met in New York in June and July that year. The Albany Plan of Union aspired to place the British North American colonies under a more centralized government. On July 10, 1754, representatives from seven British North American colonies adopted the plan. Although never carried out, the Albany Plan was the first vital proposal to unite the colonies under one government. The message is that the people are the snake, ready to strike at the boot of oppression. While made into a banner in modern times, some historians question its use as a cloth flag during colonial times.

1765 Sons of Liberty (Stamp Act)

Sons of Liberty was a clandestine organization active in the Thirteen American Colonies. It worked to advance the colonist’s rights and to fight taxation by the British government. It played a significant role in most colonies battling the Stamp Act of 1765. The secret society was instrumental in guiding the independence movement. Its flag of nine vertical stripes likely represented the Loyal Nine. Also known as the Liberty Flag, the Sons changed it to 13 horizontal stripes after the 1773 Boston Tea Party.

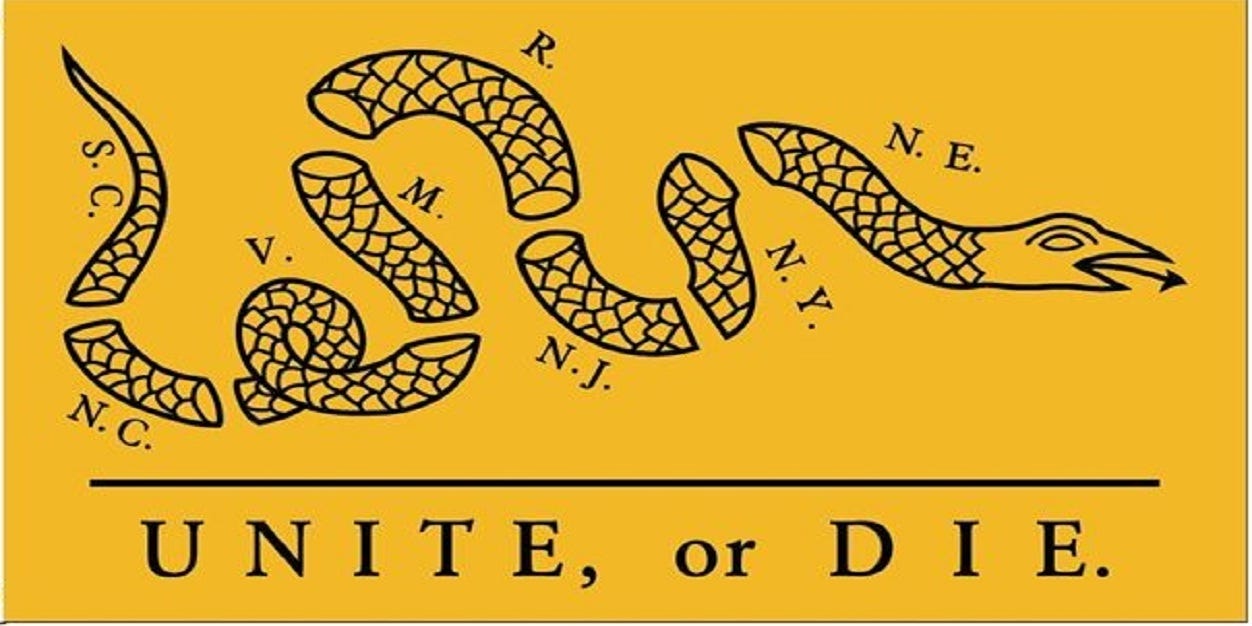

1774 Unite or Die

Franklin recast his 1754 snake drawing in the masthead of The Pennsylvania Journal in 1774 and 1775, switching the phrase to “Unite or Die.”

1774 Taunton

Taunton, Massachusetts, was a hotbed of rebellious zeal. The town had sent lawyer Robert Treat Paine to the First Continental Congress. Tauntonians erected the Taunton Flag on a 112-foot “Liberty Pole” on October 21, 1774. As a British ensign flag, it had the words “Liberty and Union” sewn on it. Some documents suggest that independence advocates displayed this flag colony-wide with just the word “LIBERTY.”

1775 Washington Cruisers

New Hampshire’s oppressive pine tree laws sparked a little-known colonial uprising in 1772 called the Pine Tree Riot. A year later, an early test of British royal authority may have encouraged the Boston Tea Party (December 16, 1773). The Tree Flag features a pine tree with the motto “An Appeal to Heaven.” Sometimes it displayed “An Appeal to God.” This icon came into formal use in October 1775. George Washington commissioned a squadron of six cruiser ships and flew this flag. The flag’s design came from General Washington’s secretary, Colonel Joseph Reed. The pine tree had long been a New England symbol depicted on the New England Flag flown by colonial merchant ships dating back to 1686. Leading up to the Revolutionary War, it became a symbol of Colonial ire and resistance.

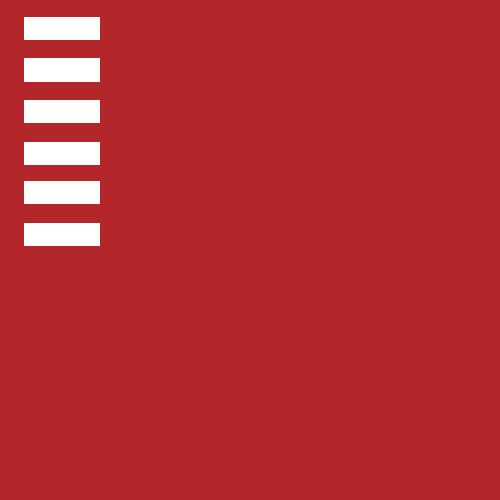

1775 Manchester Militia Company

This flag was likely the flag of the Manchester Militia Company. Mobilized on April 19, 1775, it did not enter the Battles of Lexington and Concord. The original had British iconography, and the Militia removed them and substituted the 13 white stripes (six side A and seven side B). The flag had a companion flag later turned into a dress. Recent research indicated that this flag relates to the “Grand Divisional” militia flags used to signal movement. The flag is the earliest to use 13 stripes to connote the original colonies.

1775 First Navy Jack

The image of a snake and the “Don’t Tread on Me” motto first appeared on the First Navy Jack, flown by the Continental Navy in 1775. The U.S. Navy authorized display from the jackstaff of commissioned U.S. Navy vessels while mooring pier side or at anchor.

1775 Green Mountian Boys

Ethan Allen and his cousin Seth Warner hailed from the New Hampshire land grant that became Vermont. They commanded a New Hampshire and Vermont militia brigade known as the Green Mountain Boys. The company achieved a notable victory on May 10, 1775. They invaded the British-held Fort Ticonderoga in New York State and demanded surrender. The contingent transported the captured cannon and mortars across the snow-covered mountains. The surprise installation of some of these armaments on the heights over Boston Harbor enforced Washington. Thus the British departed the critical harbor. During the Battle of Bennington on August 16, 1777, the Green Mountain Boys fought under General John Stark. The flag’s green field exemplified the Green Mountain Boys in the forest carrying the flag. Red and white stripes would pose camouflage issues. As in many American flags, the stars appear in an arbitrary arrangement. The stars signified the unity of the Thirteen Colonies in their struggle for independence.

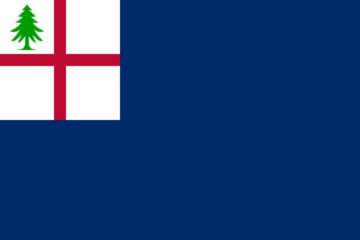

1775 Continental (Bunker Hill)

Bunker Hill and Breeds Hill are on Charlestown Peninsula across the Charles River from Boston. On June 17, 1775, the battle of Bunker Hill occurred, but most of the struggle transpired on Breed’s Hill. American colonists surrounded Boston, which was full of British troops at the time. The colonists received word the British would attempt to break out of Boston a few days before the 17th. They sent 1,200 men under the command of William Prescott into the quiet of the night and built fortifications on those two hills. Historical records provide an inconclusive account of the flag, if any, displayed at the battle.3

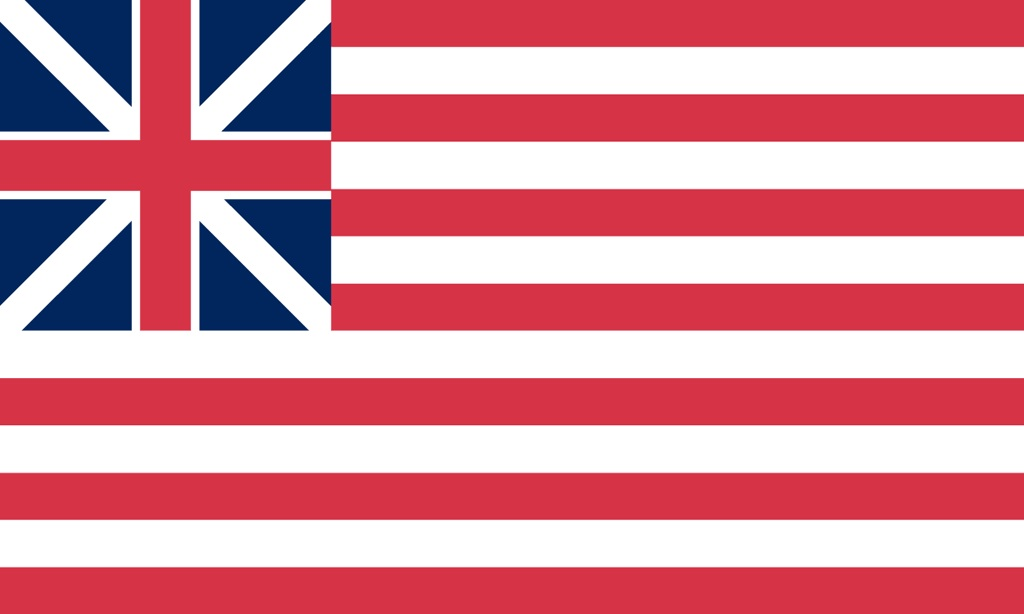

1775 Grand Union

The Grand Union flag is also known as the “Continental Colours,” the “Congress Flag,” the “Cambridge Flag,” and the “First Navy Ensign.” It is the first national flag before the Declaration of Independence. Like the current U.S. flag, the Grand Union has 13 alternating red and white stripes, representing the Thirteen Colonies. The upper inner corner, or the canton, featured the flag of the Kingdom of Great Britain, of which the colonies had been subjects. Under this flag, not Betsy Ross’s famous creation, the Continental Congress first met. George Washington commanded his troops under this flag during the early part of the war. The first display of this flag occurred on July 3, 1775. Washington took Command of the Continental Army in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

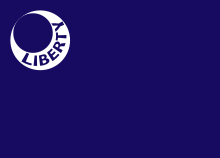

1775 Moultrie

In 1775, the Revolutionary Council of Safety asked Colonel William Moultrie to design a South Carolina flag. The South Carolina troops used it during the American Revolutionary War. It had the Militia’s uniform blue color and a crescent from their cap insignia. It first flew at Fort Johnson in defense of a new fortress on Sullivan’s Island. Moultrie faced off against a British fleet that had not lost a battle in a century. The British shot down the flag in the 16-hour combat on June 28, 1776. Sergeant William Jasper ran out into the open, raising it and rallying the troops until it mounted again. This gesture was heroic, saving Charleston from conquest for four years. The flag symbolized the Revolution and liberty in the state and the new nation. Known as the Liberty Flag or Moultrie Flag, it became the standard of the South Carolinian militia. Upon liberation, Major General Nathanael Greene presented it in Charlestown at the war’s end. Greene described it as the first American flag to display in the South. Some historical references show the word “LIBERTY” on this flag.

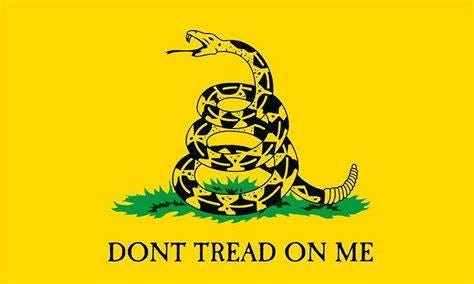

1775 Gadsen

In February 1775, Colonel Christopher Gadsden (South Carolina representative) presented this new naval flag to Congress in Philadelphia. Sea-going soldiers who would become the United States Marines used this flag. Commodore Esek Hopkins, the first Commander in Chief of the New Continental Fleet, used the Gadsen flag in February 1776. It appeared on his ships out to sea for the first time. Other flags with the rattlesnake symbol were prevalent in Rhode Island.

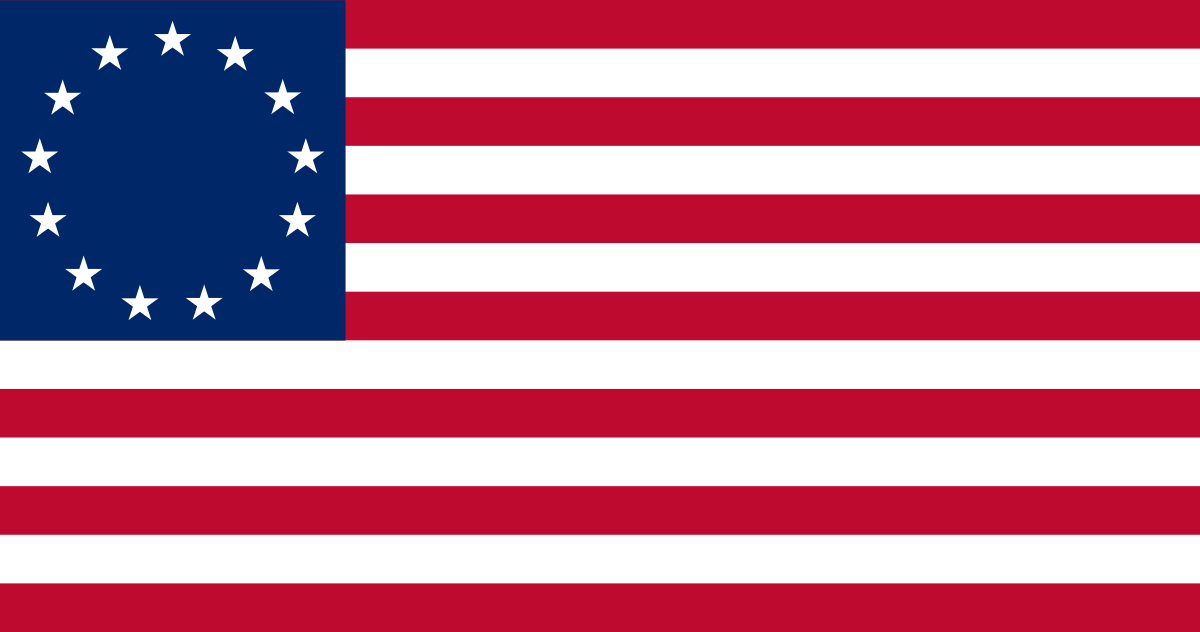

1776 Betsy Ross

Betsy Ross received a committee of three men in late May or early June of 1776: General George Washington, financier of the Revolutionary War Robert Morris, and Colonel George Ross, a relative. During this meeting, the committee allegedly presented her with a sketch of a flag featuring 13 red and white stripes and 13 six-pointed stars. They asked if she could create a flag to match the proposed design, which she joyfully obliged. In June 1777, Thomas Green, a Native American, sought the protection of an official flag while traveling. He requested Congress settle on the exact look of the United States flag. To set things in motion, he offered a payment of three strings of wampum — a traditional shell bead of the Eastern Woodlands tribes. Congress obliged. Within ten days, Congress approved (June 14, 1777 - Flag Day) the flag, featuring 13 stars and 13 stripes (representing the original 13 colonies). The Continental Congress on this day resolved, “That the flag of the United States be thirteen stripes alternating red and white; that the Union be thirteen stars, white in a blue field, representing a new constellation.” The circular design probably was by George Washington, Francis Hopkins, and Betsy Ross. Congress did not specify an arrangement for the stars in the canton. As a result, many variations of the flag followed until 1821.

1776 Easton

According to local legend, Easton, Pennsylvania leaders hoisted the flag on July 8, 1776. On that day, Robert Levers read the Declaration of Independence two days before a copy of the Declaration reached New York City. This flag accompanied Captain Abraham Horn in the War of 1812, and some suspect that the design may only date from this era. Some consider this unlikely, as flags would have had 15 stars and stripes in 1814. In 1821 after the War 1812, it returned to Easton, and town managers assigned it to the Easton Library for safe-keeping. The Easton Area Public Library still holds the flag.

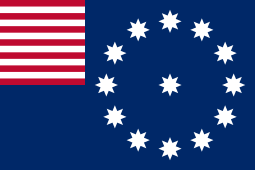

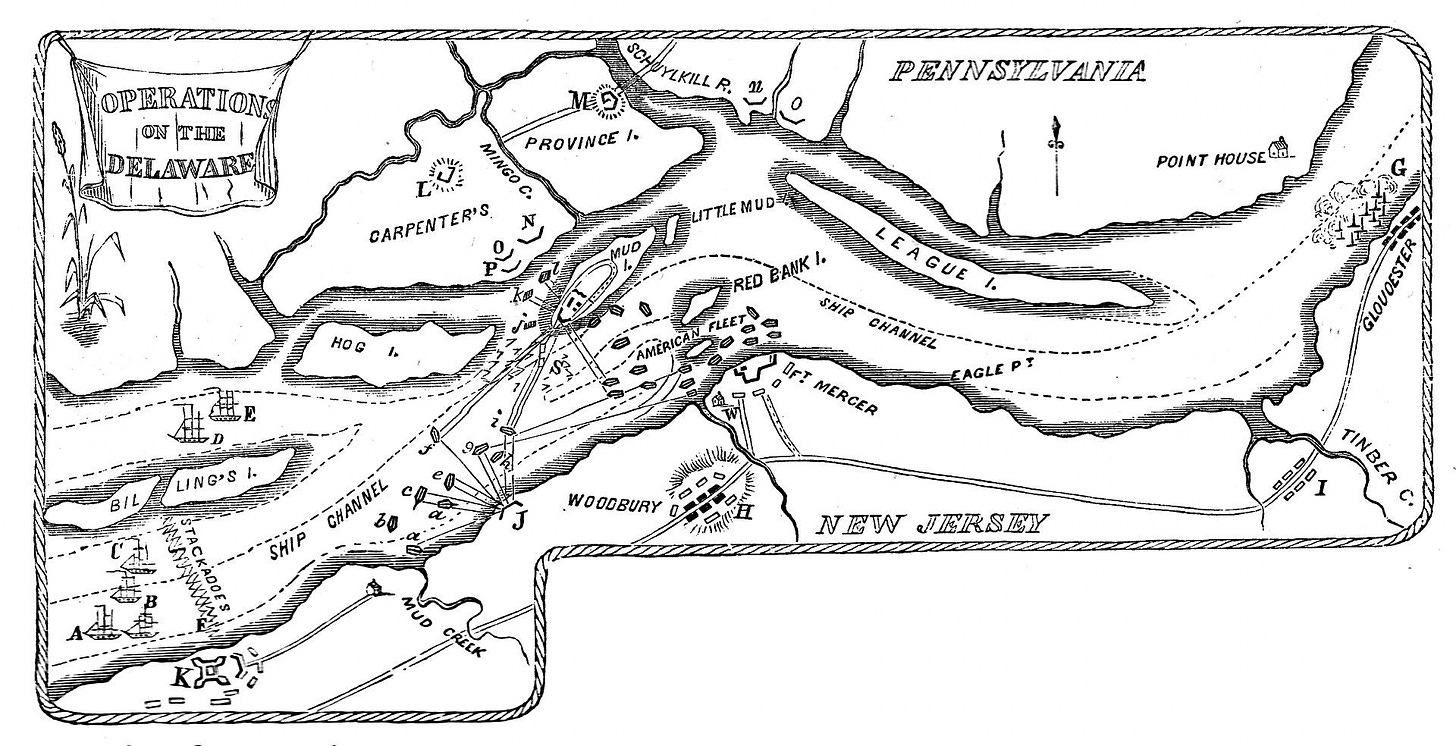

1777 Fort Mercer

In 1777, Continental Troops constructed two forts on the Delaware River south of Philadelphia. Fort Mifflin on the Pennsylvania side and Fort Mercer on the New Jersey side.4 If Americans held both defenses, the British army in Philadelphia could not communicate with the outside world or get resupplied. Under orders from General William Howe in Philadelphia, General Charles Cornwallis, with 5,000 men, attacked Fort Mercer with 5,000 troops. He landed them by ferry three miles south of the Fort. Rather than let the overwhelming British forces capture the garrison, Colonel Christopher Greene abandoned Fort Mercer on November 20, 1777. The British occupied it the following day. The British then began an assault on Fort Mifflin. For unknown reasons, this unusual 13-star flag, flown at Fort Mercer, reversed the standard red and blue colors.

1777 Fort Mifflin

The defenders of Fort Mifflin borrowed a Navy Jack flag because the navy was operating in the vicinity of the Delaware River forts. The flag remained flying during the 5-day siege of Fort Mifflin (November 10-15, 1777). It survived despite the most extensive bombardment in North American history, with over 10,000 cannonballs shot at the Fort. After the British shot it off the pole, two soldiers perished while raising it again. That was the only time the flag wasn’t flying throughout the constant barrage. Although the Continentals did not surrender to the British, they evacuated because of the extensive damage, fleeing to New Jersey. This flag design still flies over the restored Fort.

1777 Cowpens

According to some sources, this flag first appeared in 1777. The Third Maryland Regiment used it. Continental troops first carried it at the Battle of Cowpens, which took place on January 17, 1781, in South Carolina. The actual flag from that battle hangs in the Maryland State House.

1777 (circa) Hopkinson

Many acknowledge the first design as we know it today to New Jersey Congressman Francis Hopkinson, who also signed the Declaration of Independence. His reported design had thirteen six-pointed stars. Although no original example or drawing remains, the Congressional Bill bill for its design exists. For his work, Hopkins asked Congress for a quarter-cast of public wine. No record exists of Congress compensating him. Some historians suggest that a similar design existed before Betsy Ross assembled her flag. Some favor 5-pointed stars or rows of 4-5-4, but since Hopkinson’s design sketch has not definitively survived; it is a hypothesis. Other historians believe the stars were in a circular pattern (i.e., Betsy Ross).

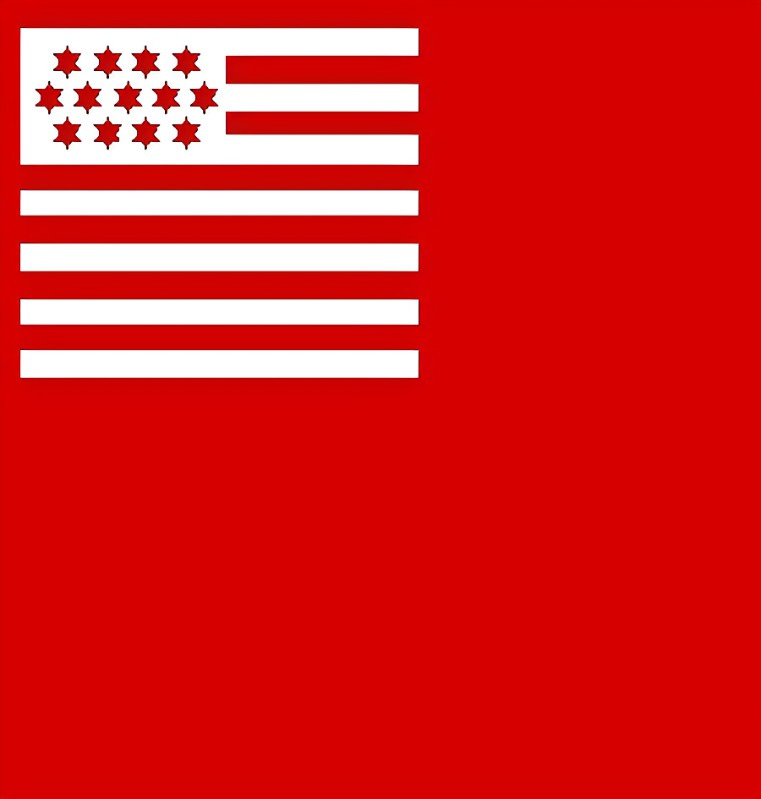

1777 Brandywine

This flag received its name for use in the Battle of Brandywine, Pennsylvania, on September 11, 1777. The red flag includes a red and white American flag image in the canton. Other stories state that the flag may have flown earlier, at the Battle of Cooch’s Bridge in Delaware on September 3, 1777. Captain Robert Wilson may have also brought it to the Battle of Paoli, Pennsylvania, on September 21, 1777. He may have also displayed it at the Battle of Germantown, Pennsylvania, on October 4. Erroneous research of this flag in 1931 resulted in it mistakenly tied to the wrong Robert Wilson and the 7th Pennsylvania Militia Regiment. Recent research indicates that this flag was the color of the Chester County Militia. Lieutenant Colonel Robert Wilson of Chester County, Pennsylvania, served under this Militia. He was responsible for the Militia’s equipment and this flag’s survival.

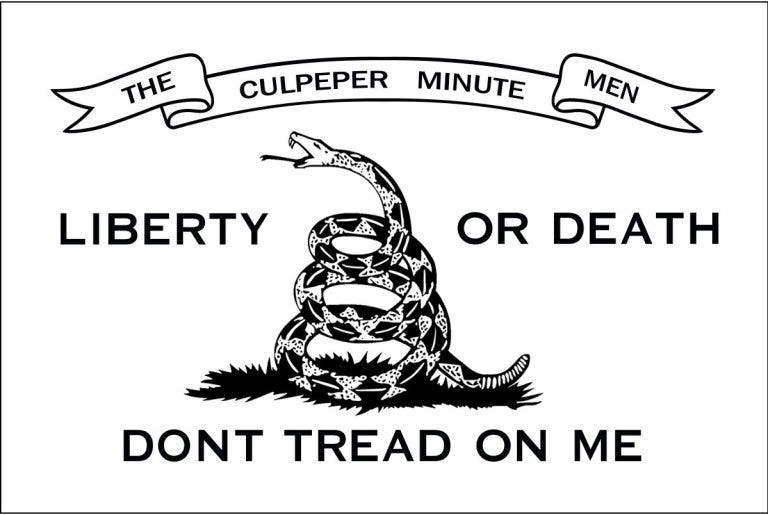

1777 Culpeper Minutemen

Minutemen from Culpeper, Virginia, displayed this flag as part of Colonel Patrick Henry’s First Virginia Regiment of 1775. Three hundred Culpeper Minutemen led by Colonel Stevens marched toward Williamsburg. Their unusual dress alarmed the people as they marched through the country. They had bucktails in their hats, tomahawks, and scalping knives hung from their belts. On each side were the words of Patrick Henry “LIBERTY OR DEATH!”

1777 Bennington

According to some accounts, Continental troops flew this flag at the Battle of Bennington, Vermont, in August 1777. It is sometimes called the Fillmore Flag. The story goes that Nathaniel Fillmore took this flag home from the battlefield and passed it down through generations of Fillmores, including Millard Fillmore (13th President of the United States), and today it can be seen at Vermont’s Bennington Museum.

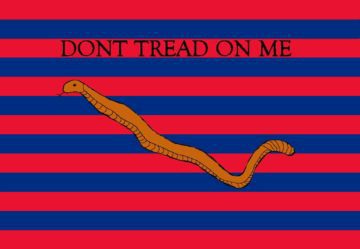

1778 South Carolina Naval Ensign

That was the flag of the South Carolina Navy during the American Revolutionary War. It is essentially the same as the Continental Naval Jack. With this flag, the motto “DON’T TREAD ON ME” appears on the third red stripe from the top and uses the colors of Scotland (blue) and England (red).

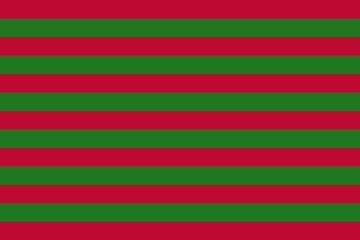

1778 George Rogers Clark

General George Rogers Clark used this red and green striped flag during his attack on the British-held Fort Sackville during the American Revolution in 1779. Fort Sackville was a British outpost located in the frontier settlement of Vincennes. His celebrated capture of Kaskaskia in 1778 and Vincennes in 1779 weakened British influence in the Northwest Territory. Since Clark was the highest ranking Continental officer to operate in the future Northwest Territory, he is known as the “Conqueror of the Old Northwest.”

1779 Serapis or Texel

Serapis, also called Texel, is an unconventional, early United States ensign. It accompanied the captured British frigate Serapis. U.S. Navy Captian John Paul Jones captured the Serapis at the 1779 Battle of Flamborough Head. His ship, the Bonhomme Richard, lost its flag from the mast into the sea during the battle and sank. Jones, now commanding the Serapis without a U.S. ensign to display, sailed to the island port of Texel, a Dutch United Province. Officials from Britain argued that Jones was a pirate since he sailed a captured vessel flying no known national ensign. The Ambassador to France, Benjamin Franklin, gave a vague recollection provided the design of the flag. Artists painted for the French court to recognize it. Copies went to various European ports, including Texel. The harbor master at Texler showed John Paul Jones the drawing of Franklin’s version of the American flag. Jones had one made and raised this flag when he sailed back to the colonies on the Alliance.

1781 Guilford Courthouse

On March 15, 1781, the North Carolina militia reportedly displayed this banner at the Battle of Guilford Courthouse, Greensboro, North Carolina. The flag is recognizable by the reverse colors usually seen on American flags. The field has red and blue stripes with eight-pointed blue stars on an elongated white canton.

Simcoe Yorktown Flag 1781

During the Battle of Yorktown in October 1781, this flag flew on the right flank of the American troops. A 26-year-old British Lieutenant Colonel named John Graves Simcoe, in command of the Queen’s Rangers at Yorktown painted this from his station across the river. Many flag historians believe that the flag was between Simcoe and his position at Gloucester Point and the sun, thus resulting in the strange colors he perceived. After the war, Simcoe became Upper Canada’s first lieutenant governor and probably the most influential British official dispatched from London to preside over a Canadian province.

1781 Bauman Yorktown

An American artillery officer drew a map within days of the British surrender at Yorktown on October 19, 1781. Major Sebastian Bauman (2nd New York Artillery Regiment) drew the map also showing this flag. Bauman served in New York, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania campaigns. He commanded the artillery at West Point before joining Washington at the siege of Yorktown. Bauman surveyed the terrain and battle positions at Yorktown. He emigrated to America from Germany after service in the Austrian army. Robert Scot of Philadelphia engraved and published the flag.

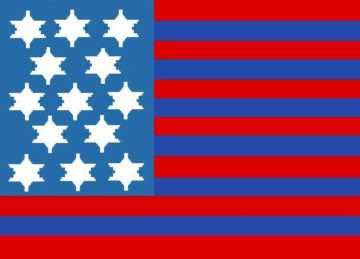

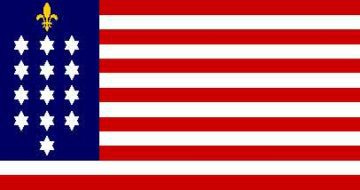

1781 United States-French Alliance Flag

A special U.S. Flag appeared in 1781 and 1782. It honored the end of the American Revolutionary War and the help of France in that conflict. It consisted of very long 13 red and white stripes. The canton displayed either 12 or 13 white stars and a gold fleur-di-lis. The stars appear in contemporary illustrations as five-pointed or six-pointed. There are rows with three stars, with a single star below and a fleur at the top.

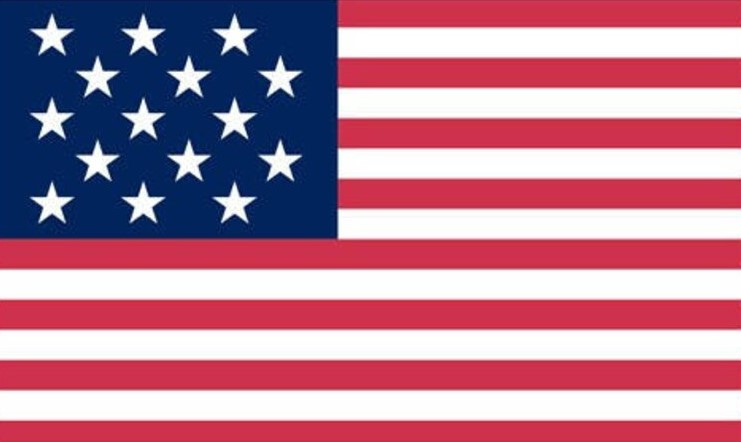

1795 Star-Spangled Banner

Flag with 15 stars and 15 stripes Vermont (March 4, 1791), Kentucky (June 1, 1792). It raised over Fort McHenry on the morning of September 14, 1814, to signal American victory over the British in the Battle of Baltimore in the War of 1812. The sight inspired Francis Scott Key to write “The Star-Spangled Banner.”

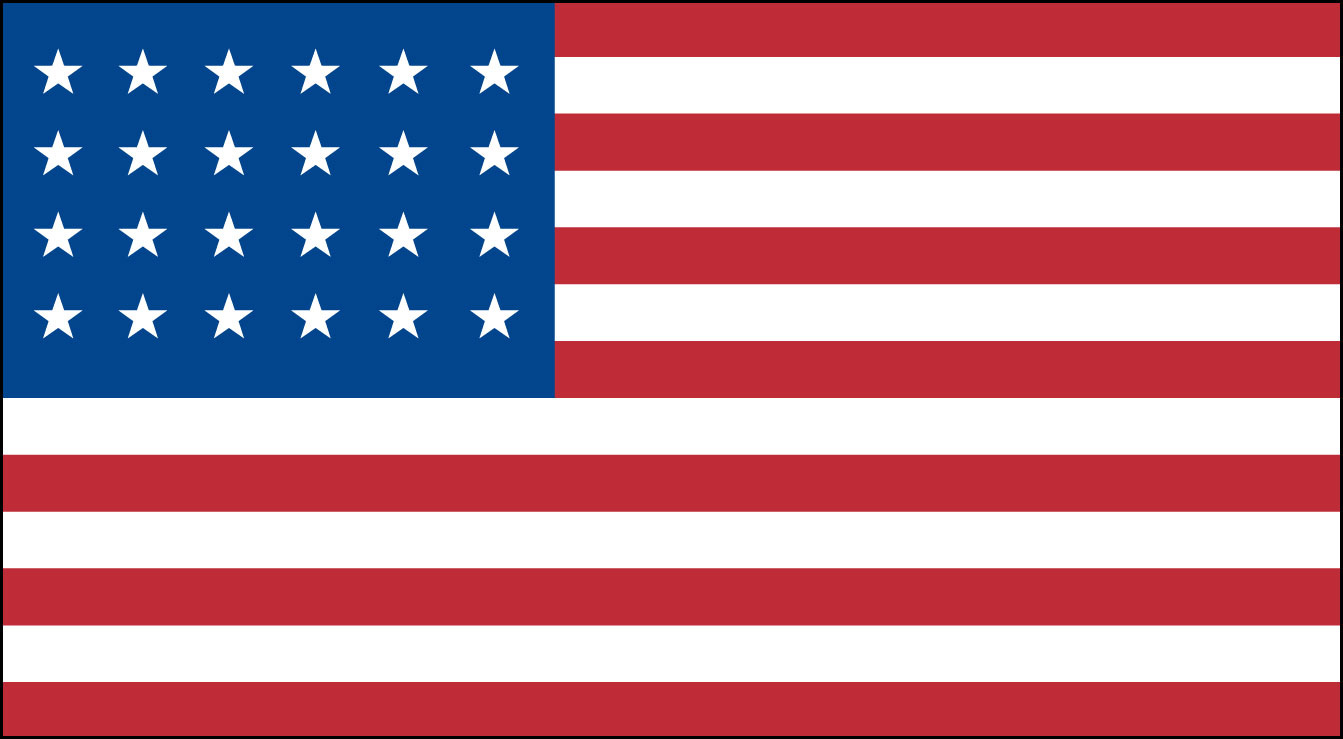

1817 Twenty Star

Flag with 20 stars and 13 stripes (it remains at 13 hereafter) Tennessee (June 1, 1796), Ohio (March 1, 1803), Louisiana (April 30, 1812), Indiana (December 11, 1816), Mississippi (December 10, 1817)

1803 Indian Peace

The American government often presented the Stars and Stripes to friendly Indian nations. These “Indian Peace” flags displayed the U.S. Coat of Arms in the canton.

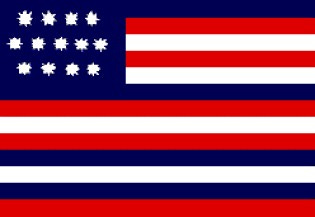

1818 Great Star

In 1818, several Great Star flags appeared. This flag flew over the Capitol dome for at least six months in 1818.

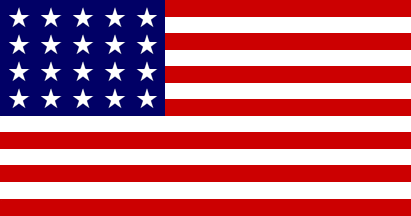

1821 Twenty-Four Star

Flag with 24 stars, Missouri (August 10, 1821). This layout perhaps first exemplifies the look of the flag as we know it today.

Afterword

The name Old Glory describes a large, 10-by-17-foot flag by its owner, William Driver, a sea captain from Massachusetts. That inspired the common modern nickname for all American flags. Driver’s flag survived many attempts to deface it during the Civil War. Captain Driver was able to fly it over the Tennessee Statehouse once the Civil War ended.

Author and publisher, Frederick R. Smith

Sources

Encyclopedia of the American Revolution - Mark M. Boatner III, 1392 pages, Stackpole Books, August 1994 (reprint of 1966 original)

List of Flags during the American Revolutionary War from 1775-1883

Flag Definition & Meaning - Merriam-Webster

Bedford Free Public Library Trustees Minutes for Tuesday, April 12, 2022, contrary to other records (1720), indicate the Bedford Flag appeared in 1713.

The flag, if any at the battle, is in dispute. John Trumball, the famous artist of the period, witnessed the Battle of Bunker Hill from a distance and created several renderings that show a red or blue flag.

Given the above, one of the following banners could have been the “Bunker Hil” or “Continental” flag.

Subscribe to Frederick R. Smith Speaks

The Frederick R. Smith blog is the ramblings of an uncommon man in a post-modern world. As a master of few topics, your author desires to give readers a sense of the thoughts of a senior citizen who lived most of his life before the new normal.

![[Indian Peace Flag] [Indian Peace Flag]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_lossy/https%3A%2F%2Fbucketeer-e05bbc84-baa3-437e-9518-adb32be77984.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F37c6760a-f4ca-4b44-a604-39eb2ef5d0b0_324x221.gif)

![[U.S. 20 Great Star flag] [U.S. 20 Great Star flag]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_lossy/https%3A%2F%2Fbucketeer-e05bbc84-baa3-437e-9518-adb32be77984.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F3cccc5f9-8195-422a-9924-9484d9ef3dca_363x216.gif)

More flags of note! https://gadsdenandculpeper.com/products/copy-of-pc-happy-face-black-t-shirt

Love the history lesson. I am terrified we will lose our Republic to the Evil in and out of the WH, Congress, to the Great Rest. More and more it looks like the first Great Depression. This jobs report was a farce. the next one will be worse. The Spending bill worse. People have closed blind eyes, as government takes over more of their lives. As Franklin said " Those who sacrifice liberty for security/safety deserve neither. " " He who sacrifices freedom for security/safety deserves neither. "

Looking forward to your History of the Ladies of the RW. They were dismissed as ornaments or Breeders to stupid to understand.