Discover more from Frederick R. Smith Speaks

Engineering Masterpiece: Horseshoe Curve

Horseshoe Curve just west of Altoona, Pennsylvania is a remarkable engineering marvel and pivotal point in American history.

Now that I have flagged Thee, lift up my feet from the road of life and plant them safely on the deck of the train of salvation. Let me use the safety lamp of prudence, make all couplings with the link of love, let my hand-lamp be the Bible, and keep all switches closed that lead off the main line into the sidings with blind ends. Have every semaphore white along the line of hope, that I may make the run of life without stopping. Give me the Ten Commandments as a working card, and when I have finished the run on schedule time and pulled into the terminal, may Thou, superintendent of the universe, say, “Well done, good and faithful servant; come into the general office to sign the pay-roll and receive your check for happiness.”1

Words: 3,361 ~ Read time: 14 min

Foreword

In 1977, as a young track laborer a few years into my railway career, I embarked on a journey that would lead me to follow in the footsteps of the men who built an iconic engineering masterpiece. That summer, the railroad assigned me to work from a camp car train 100 miles east of this engineering marvel. I felt proud and honored to work on the same railroad main line running through the Horseshoe Curve. Moreover, in the last 12 years of my career, I managed a railroad safety inspection workforce throughout the mid-Atlantic region. That region included the Horseshoe Curve. It is one of the high points of my lifelong study of railroad engineering and history. Since I was a teen, I visited the curve often for work and pleasure. That sets the stage for the following virtual trip to the Horseshoe Curve. You will discover triumph, intrigue, tragedy, and the sight and sound of a modern freight train passing by on the curve.

Introduction

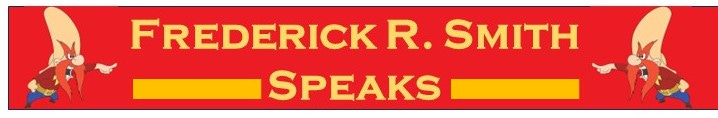

Horseshoe Curve is just west of Altoona, Pennsylvania. It is a remarkable engineering feat that was pivotal in American railroad history. The Pennsylvania Railroad (PRR) built the Horseshoe Curve in the mid-19th century. A sharp bend in the tracks lets trains climb the Allegheny Mountains. This iconic curve has facilitated transportation. It has become a symbol of ingenuity and perseverance in challenging terrain.

The idea for Horseshoe Curve emerged in the early 19th century. Railroads sought to connect the burgeoning industrial centers of the eastern United States. They wanted to connect them with the natural resources and markets of the Midwest. Yet, the rugged terrain of the Allegheny Mountains was a formidable obstacle to westward expansion. Engineers faced the daunting task of devising a route. It would enable trains to navigate the landscape’s steep gradients and sharp curves.

The solution came in the form of a Horseshoe Curve. It’s a horseshoe-shaped bend in the tracks. That reduced the gradient and allowed trains to ascend the mountains gradually. The construction of the Horseshoe Curve began in the 1850s. PRR Chief Engineer J. Edgar Thomson (1808-1874) oversaw the surveying and grading of the route. Thousands of laborers, including immigrants and formerly enslaved men, toiled under grueling conditions. They carved out the curve from the rocky terrain.

Horseshoe Curve opened on February 15, 1854. That marked a significant milestone in American railroad history. The completion of the curve revolutionized transportation in the region. It facilitated the movement of goods, passengers, and mail between the eastern seaboard and the Midwest. The curve played a crucial role in the Civil War. It was a vital supply route for Union forces and a strategic target for Confederate raiders.

Over the years, the Horseshoe Curve has undergone various upgrades and improvements. These changes accommodate new technology and demands. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the curve added two tracks to make it a four-track main line. Also, the railroad added signaling systems to enhance efficiency and safety. In the mid-20th century, diesel locomotives replaced steam engines. This further modernized operations on the curve.

Today, the Horseshoe Curve remains a vital artery in the American railroad network. It is a critical link between the East Coast and the Midwest in Norfolk Southern’s mainline. The curve continues to attract railroad enthusiasts, historians, and tourists. People from all over the world visit the curve. They marvel at its impressive engineering and scenic beauty. The government designated the Horseshoe Curve as a National Historic Landmark in 1966.

The Engineering

The engineering and geometry of the Horseshoe Curve are remarkable. They represent a triumph of human ingenuity. The Allegheny Mountains posed formidable challenges. This iconic railroad curve is a testament to the vision and skill of its designers. It’s also a prime example of innovative engineering overcoming daunting natural obstacles.

The Horseshoe Curve is a massive bend in the railroad tracks. It helps trains go up or down steep mountains with less strain on the locomotives and rolling stock. The curve reduces the slope (grade) of the track, making it easier for trains to navigate the mountainous terrain. This ingenious design allows for smoother and more efficient train operations. It reduces the need for excessive locomotive power and minimizes wear and tear on the equipment.

The Horseshoe Curve follows a classic horseshoe shape. The tracks curve around the mountainside in a semi-circular arc. This distinctive layout serves several vital purposes. First, it provides a gradual transition for trains as they ascend or descend the mountain. That minimizes the risk of derailments or accidents. Second, it maximizes the distance traveled within a limited space. Such an arrangement allows for more significant elevation gain without needing steeper grades. Finally, it offers excellent visibility for train crews. That enables them to navigate the curve safely and efficiently.

Its sheer scale is one of the most impressive aspects of Horseshoe Curve’s engineering. The curve spans approximately 2,375 feet and features a radius of 619 feet. This expansive layout allows for the smooth transition of trains around the curve. It ensures stability and reliability in operation. Moreover, its elevation is about 1,300 feet above sea level. That adds to its grandeur and significance in the landscape.

Engineers faced many technical challenges in constructing the Horseshoe Curve. They had to grade the steep mountainside, excavate rock, and ensure the track bed’s stability. The project required extensive surveying, grading, and earthmoving. It also needed the construction of retaining walls and drainage systems. We needed these measures to reduce erosion and landslides. Additionally, the curve had to align with existing track sections. That ensured seamless connectivity within the railroad network.

Westward-bound trains ascend a most significant ascending gradient of 1.85 percent throughout twelve miles from Altoona to Gallitzin.2 Upon reaching the vicinity of the Gallitzin Tunnels, trains traverse the peak of the Allegheny Mountains. Then, they begin or start a 25-mile journey toward Johnstown, navigating a descending grade of 1.1 percent or lower. Norfolk Southern designates the grade at the Horseshoe Curve as 1.34 percent. It extends over a distance of 2,375 feet, with a width reaching approximately 1,300 feet at its broadest point. The 619-foot radius of the curvature equals 9 degrees-15 minutes per one hundred feet, amounting to a total curve of 220 degrees.3

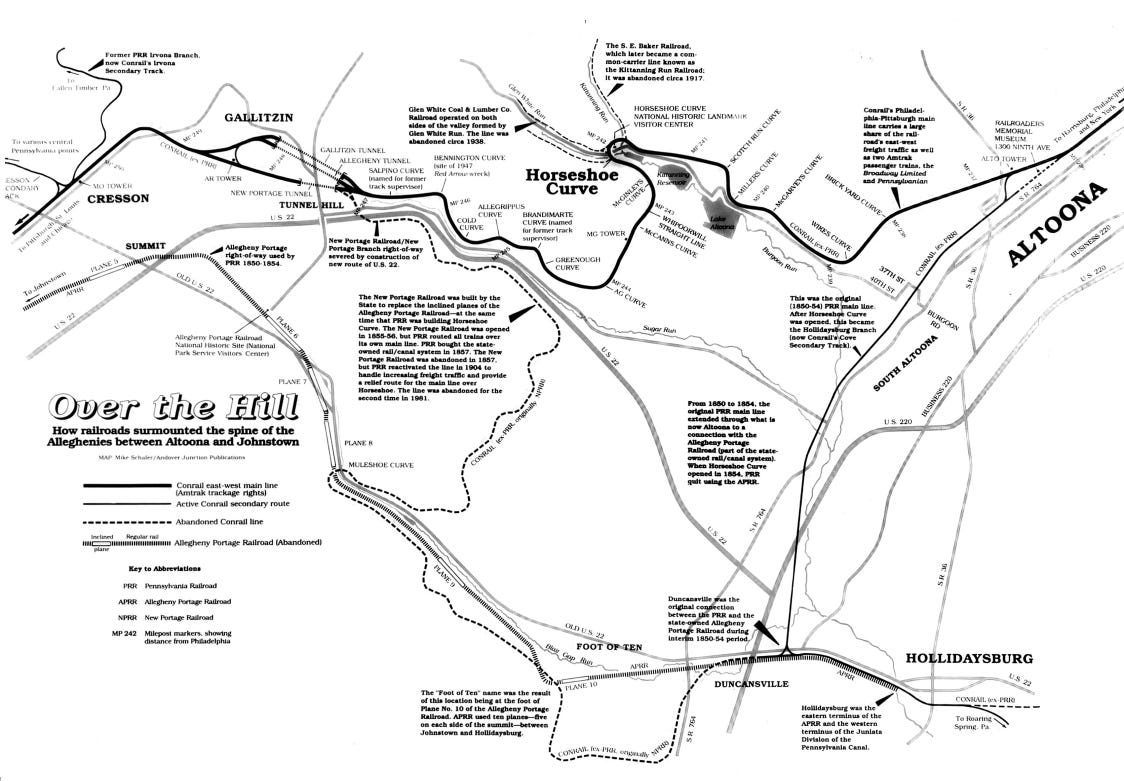

Railroaders Memorial Museum operates the public access area to the Horseshoe Curve. In addition to a museum at the site, an extensive historical railroad map on a trackside sign gives visitors a bird’s eye view of the area. Below is a photo of the sign taken by your author. To zoom up on the map’s key points, click here (courtesy HMdb.org).

Operation Pastorius

Operation Pastorius, a thwarted German espionage endeavor during World War II, aimed to infiltrate the United States to sabotage vital economic targets in the mid-Atlantic states. The most notable target was the Horseshoe Curve. Launched in June 1942 under the direction of Admiral Wilhelm Canaris (1887-1945), head of the German Abwehr, the German war machine named the operation after Francis Daniel Pastorius (1651-1720), the pioneer of the earliest German settlement in America.45 The scheme involved eight German saboteurs, all with prior residency in the United States.

Among the recruits were two American citizens, Ernst Burger and Herbert Haupt, alongside George John Dasch, Edward John Kerling, Richard Quirin, Heinrich Harm Heinck, Hermann Otto Neubauer, and Werner Thiel. Except for Dasch, the men were affiliated with the German American Bund or the Nazi Party, with Neubauer having served in the German Army on the Eastern Front.

Their objective encompassed disrupting various American economic assets, including Jewish-owned businesses in the eastern mid-Atlantic region and the strategic Horseshoe Curve. Equipped with counterfeit documents, a substantial sum of American currency, and false identities, the saboteurs sailed via two U-boats to the U.S. East Coast.

Under the tutelage of the Abwehr, all eight underwent rigorous sabotage training at the German High Command school near Berlin. They received instruction in construction and explosives, incendiaries, and various timing mechanisms. Instructions emphasized crafting credible backgrounds to assimilate into American society, with language proficiency and cultural assimilation integral to their preparation.

On the night of June 12, 1942, U-202, the first submarine carrying saboteurs, landed at Amagansett, New York, east of New York City. Disguised in German Navy uniforms, the team buried their equipment and transitioned into civilian attire to commence their mission. However, their plans got foiled when Coast Guardsman John C. Cullen discovered Dasch among the dunes. Despite Dasch’s attempted bribery, Cullen alerted authorities, initiating a manhunt.

Meanwhile, another team led by Kerling landed without incident south of Jacksonville at Ponte Vedra Beach, Florida, on June 16, 1942. Transitioning from bathing suits to civilian clothing, they began their mission by boarding trains to Chicago and Cincinnati.

The rendezvous for both teams was set for July 4 in a Cincinnati hotel to synchronize their sabotage efforts. However, the plan unraveled after Dasch and Burger defected to the Federal Bureau of Investigation, betraying their comrades. Subsequently, all eight saboteurs were sentenced to death by a military tribunal, although Roosevelt commuted Dasch and Burger’s sentences. In 1948, the U.S. government deported them to the American occupation zone in Germany under President Truman’s executive clemency.

And now it is time to get some popcorn and liquid refreshment. Come back and relax to watch the full-length motion picture about Operation Pastorius. Introducing They Came to Blow Up America starring George Sanders (1943).

The Red Arrow - Tragedy Near the Curve

Throughout its history, several accidents occurred on or near the curve. One stands out as the most sensational and deadly, the wreck of the Red Arrow.

Around 3:22 AM on Tuesday, February 18, 1947, tragedy struck as Train No. 68, known as The “Red Arrow,” was en route from Detroit to New York City. The eastbound passenger train had sleeping cars. It encountered disaster near the Gallitzin Tunnels, two miles west of the Horseshoe Curve (please see the above map showing the precise location).

The train was going over 50 miles per hour down the grade. The train derailed and careened into a 200-foot-deep gorge. That happened at Bennington Curve, half a mile east of Tunnel Hill at Gum Tree Hollow. The chilling weather conditions may have contributed to the loss of control. Speculations of ice on the rails also played a role. The engineer and crew made efforts but couldn’t regain control.

The train had 155 people aboard, including two engines, a baggage car, a coach, a mail car, and two sleeper cars. Its descent down the steep embankment was disastrous. Eleven out of fourteen cars left the rails, leaving chaos and devastation in their wake. The crash occurred on the slope leading to Cresson Mountain. Cresson Mountain is the highest section of the Allegheny Mountains. Its altitude exceeds 2,100 feet.

Rescue efforts commenced. But reaching the survivors stranded on the cold mountainside took time. Witnesses described surreal devastation. Train cars lay scattered at odd angles along the embankment. Miscellaneous items were strewn about, reminiscent of a surreal nightmare. Inside the coaches, panic and chaos reigned. Passengers struggled to free themselves from the twisted wreckage. Others cried out for help and searched for loved ones.

Among the heroes emerged Reverend Liberman of Canton, Ohio. He remained with his fellow passengers, offering prayers and comfort until help arrived. Despite the grim circumstances, stories of resilience and compassion emerged amidst the tragedy.

In the end, the wreck claimed twenty-four lives, with most people dying upon impact. The Bennington Curve and the Gallitzin Tunnels bear the mark of this catastrophic event. Since then, The Wreck of the Red Arrow has gained a haunting reputation in local lore. Tales of potential hauntings echo through the surrounding landscape. The bottom line of the Interstate Commerce Commission’s accident report states: “It is found that this accident was caused by excessive speed on a curve.”

Twilight of the Pennsylvania Railroad and Today

At its height in the 1940s, late-night curve action defies imagination. Between 10:45 PM and 3:41 AM, twenty-eight famous PRR blue ribbon passenger trains rounded the curve in both directions. In the 20th century, there were economic challenges. Competition from other modes of transportation and regulatory changes also posed challenges. That led to the consolidation of many railroad companies. In 1968, the PRR merged with its rival, the New York Central Railroad, to form the Penn Central Transportation Company. Yet, Penn Central faced financial difficulties. It became part of the Consolidated Rail Corporation (Conrail) in 1976. A few other bankrupt northeastern railroads joined it. During the Conrail era, which lasted until the 1990s, the Horseshoe Curve operated as a vital segment of the railroad network. Conrail decided to remove one of the four tracks at Horseshoe Curve. That was to streamline operations and reduce maintenance costs.

In 1998, Norfolk Southern and CSX Transportation acquired significant portions of Conrail’s assets. That included its tracks, facilities, and rights-of-way. Norfolk Southern gained control of the former PRR mainline in this transaction. The acquisition included the Horseshoe Curve and its infrastructure. They’ve kept it as a critical part of their network. The company has invested in maintaining and upgrading the curve. That ensures its safety and efficiency for freight and passenger train operations.

As part of Norfolk Southern’s Pittsburgh Line, the curve remains a bustling thoroughfare. Today, it boasts more than fifty scheduled freight trains per day. That number does not factor in locals and helper engines, which could effectively double the traffic. Helper engines are typically attached to the rear of lengthy trains. They provide additional power for ascents and assist with braking during descents.

In 2012, Norfolk Southern reported that 111.8 million gross tons passed through the Horseshoe Curve annually. This traffic included locomotives. Amtrak’s Pennsylvanian service between Pittsburgh and New York City passes once in each direction every day. Freight trains can travel at a maximum speed of thirty miles per hour through the Horseshoe Curve. Passenger trains can reach speeds of approximately thirty-five miles per hour. Enjoy the following breathtaking video of a westbound (uphill) modern freight train recorded by your author at the Horseshoe Curve on June 14, 2023.

Conclusion

Horseshoe Curve is a testament to the ingenuity, perseverance, and vision of the engineers and laborers who built it. This iconic railroad landmark has played a pivotal role in American history. It facilitated westward expansion, supported economic growth, and connected communities nationwide. The Horseshoe Curve is a symbol of innovation and progress. It continues to inspire awe and admiration for the remarkable achievements of the railroad industry.

The engineering and geometry of the Horseshoe Curve represent a triumph of human ingenuity and innovation. This iconic railroad curve embodies the principles of efficiency, safety, and reliability. It enables trains to traverse the rugged terrain of the Allegheny Mountains with ease. The Horseshoe Curve stands as a lasting symbol of the transformative power of engineering. That is a testament to the skill and vision of its designers. It shows how engineering shapes the modern world.

The Nazi plot to blow up Horseshoe Curve stands as a compelling episode in World War II history. It highlights the ingenuity of German sabotage efforts. It also shows the effectiveness of American counterintelligence. The thwarting of the plot underscores the importance of vigilance and cooperation. It demonstrates the need to work together to defend against enemy threats. The story of George John Dasch raises profound questions about wartime. That includes loyalty, betrayal, and individual moral responsibility during war.

The tragedy that befell Train No. 68, the Red Arrow, serves as a sadder reminder of the fragility of human life and the unpredictable nature of our world. It was a fateful February morning in 1947 near the Gallitzin Tunnels. The train careened off the rails and into the depths of Gum Tree Hollow. It left behind a trail of devastation and heartache. That would forever remain a part of history.

Horseshoe Curve’s evolution mirrors the broader shifts and challenges faced by the railroad industry in the 20th century. The curve was a vital segment of the Pennsylvania Railroad from its start. It has continued to be significant under the stewardship of Norfolk Southern. The curve has adapted to changing economic, regulatory, and operational landscapes. Ownership changes and operational adjustments have occurred. Horseshoe Curve remains an essential part of Norfolk Southern’s network. It allows for an efficient and reliable path for freight and passengers. The curve’s lasting importance shows its resilience and adaptability. It meets modern commerce and travel demands. 📕

Sources

Frederick R. Smith Library Books

Down Brakes A History of Railway Accidents, Safety Precautions and Operating Practices in the United States ~ Robert B. Shaw, 487 pages, P. R. Macmillan Limited, 1961

Horseshoe Curve: Sabotage and Subversion in the Railroad City ~ Dennis P. McIlnay, 456 pages, Seven Oaks Press, 2007

Image of Rail Horseshoe Curve ~ David W. Sidel, 127 pages, Arcadia Publishing, 2008

Landmarks on the Iron Road: Two Centuries of North American Railroad Engineering ~ William D. Middleton, 194 pages, Indiana University Press, 1999

Pennsy Power ~ Alvin F. Staufer, 320 pages, publisher Alvin F. Staufer, 1962

Online

Locals tell story of the Red Arrow 70 years after railroad disaster ~ Altoona Mirror, February 18, 2024

Six Nazi Saboteurs Ececuted in Washington ~ Ghostsofdc.org

The Horseshoe Curve 1858 ~ Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission

The Wreck of the Red Arrow ~ Lancaster Chapter of the National Railway Historical Society, October 2010

I warmly encourage you to consider becoming a paid subscriber if you have the means. Tips are appreciated, too. Regardless of your choice, your support is deeply appreciated. From the bottom of my heart, thank you for your invaluable support!

A Treasury of Railroad Folklore, 530 pages, Bonanza Books, 1953. Cited from Topeka State Journal, reprinted in The Railroad Man’s Magazine, Vol. I (October 1906), No. 1, pp. 133-134.

Railroad engineers express railroad track grade as a percentage, where a positive grade indicates an uphill slope and a negative grade indicates a downhill slope. For example, a 2% grade means that the track rises by two feet vertically for every 100 feet of horizontal distance.

The degree or sharpness of a railroad curve is the angle through which the track curves 100 feet. The intersection of the two radii is one degree for a curve 100 feet long with a radius of 5,729 feet at each end of the arc. For ease in fieldwork, railroads use a 100 chord; thus, Radius = 5729.67 / D and Degree = 5729.7 / Radius. In railway transit lines, engineers typically use radius only because of the sharp curves of such operations.

Admiral Wilhelm Canaris, appointed head of the Abwehr (January 1935), organized German aid to General Francisco Franco during the Spanish Civil War. Believing that the Nazi regime would ultimately destroy traditional values and that its foreign ambitions were dangerous to Germany, he enlisted some of the anti-Hitler conspirators into the Abwehr and shielded their activities. He was transferred to the economic staff of the armed forces (February 1944) after an investigation of the Abwehr by the Schutzstaffel (SS); he remained there until after the abortive assassination attempt against Hitler (July 20, 1944), when he was arrested and executed.

Germantown is a historic neighborhood in the northwest section of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Established by German immigrants in the late 17th century, Germantown is known for its rich cultural heritage, diverse population, and significant role in American history. One of Germantown’s most notable landmarks is the Germantown White House, which served as the residence of President George Washington during the 1793 Yellow Fever epidemic. Additionally, the neighborhood boasts several other historical sites, including the Concord School House, the Grumblethorpe mansion, and the Johnson House, all of which played important roles during the American Revolutionary War and the Underground Railroad.

Subscribe to Frederick R. Smith Speaks

The Frederick R. Smith blog is the ramblings of an uncommon man in a post-modern world. As a master of few topics, your author desires to give readers a sense of the thoughts of a senior citizen who lived most of his life before the new normal.

Fascinating, educational, and poetic: You won the Substack trifecta, Frederick.

Another well-written piece of history. Reminds me of the Hoover Dam Project.