Discover more from Frederick R. Smith Speaks

USA Flag - Part 2, Betsy Ross

This essay aims to shed some light on a commonly misunderstood topic: the origins of the United States flag and the historical figure of Betsy Ross.

From dusk till dawn the livelong night | She kept the tallow dips alight, | And fast her nimble fingers flew | To sew the stars upon the blue. | With weary eyes and aching head | She stitched the stripes of white and red, | And when the day came up the stair | Complete across a carven chair | Hung Betsy’s battle flag.1

Minna Irving

Foreword

Today, we live in an age where our history faces progressive scorn and general apathy. This essay aims to shed some light on a commonly misunderstood topic: the origins of the United States flag and the wonderful historical figure of Betsy Ross.

Betsy Ross History

In 1680, devout Quaker Andrew Grissom emigrated from England to the North American colony of New Jersey.2 Grissom, Betsy Ross’s great-grandfather, landed one year before William Penn founded the city of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, located on the west bank of the Delaware river. The river separates New Jersey and Pennsylvania.

As a successful carpenter in New Jersey, Grissom aspired to join William Penn’s Quaker society. In 1681, he purchased 495 acres of land in the Spring Garden area north of Philadelphia. The city later incorporated Spring Garden.

Carpenters’ Hall in Philadelphia is home to the oldest trade organization. Griscom’s son and grandson have their names inscribed on a wall at that historic spot. Grandson Samuel Griscom helped build the bell tower at the Pennsylvania State House (Independence Hall). He married Rebecca James from a prominent Quaker merchant family. Of note, it was not unusual for couples in those days to have many children.

Born on January 1, 1752, Elizabeth (Betsy) Griscom was the 8th of 17 children. She attended Friends (Quaker) public school. For eight years, Betsy received schooling in reading and writing. She also had instruction in a trade (likely sewing).

Upon completion of schooling, Betsy entered into an upholstering apprenticeship. In colonial times, that work included sofa-making and sewing, such as flag-making. During this period, Betsy fell in love with apprentice John Ross. John was the son of an Episcopal assistant rector at Christ Church.

Quakers disdained inter-denominational marriages. Quakers in such unions faced emotional and economic isolation from their family and meeting houses. On November 4, 1773, 21-year-old Betsy eloped with 21-year-old John Ross despite facing the consequences. They ferried across the Delaware River to Hugg’s Tavern in Gloucester City, New Jersey.

As expected, Betsy’s family disowned her for her marriage to John. Of note, the wedding certificate included the seal and signature of New Jersey Governor William Franklin. Three years later, William split with his father (Benjamin Franklin) because he was a Loyalist rebuffing the Revolution.

Two years after marriage, John and Betsy started their own upholstery business. It was tough going as the Quaker community shunned their products. On Sundays, John and Betsy sat in pew 12 at Christ Church. On some Sundays, George Washington, the new commander-in-chief, sat next to Ross’s pew.

In early 1776, the colonists started to call for the end of rule under the King. Thomas Paine’s booklet “Common Sense,” published in January 1776, spurned a sentiment. It fueled the desire for independence throughout the colonies. In Common Sense, Paine writes, “These are the times that try men’s souls.” The booklet swelled rebellious hearts and sold 120,000 copies in three months and 500,000 copies before the war’s end. But, Philadelphia faced a fracture in its loyalties. Many still felt themselves citizens of Britain (Loyalists), while others were ardent revolutionaries.

The war affected Betsy and John Ross’s business. Fabrics were hard to come by, and business was slow. John joined the Pennsylvania militia. In mid-January 1776, an explosion occurred while John guarded an ammunition stockpile. That incident wounded John Ross. Betsy attempted to nurse him back to health, but he died on January 21. John’s burial occurred at Christ Church.

According to Betsy, as related to us by her descendants, she met with an informal committee in late May or early June of 1776. The group included George Washington, George Ross, and Robert Morris, which led to the sewing of the flag. It is likely that Colonel George Ross—a signer of the Declaration of Independence and her husband’s uncle—recommended her for the job.

During this meeting, the group presented a sketch of a flag featuring 13 red and white stripes and 13 six-pointed stars. They asked Betsy if she could create a banner to match the proposed design. Ross agreed but suggested a couple of changes. That included arranging the stars in a circle and reducing the points on each star to five.3

The following year, on June 14, 1777, Congress adopted the Stars and Stripes. The day after, widowed Betsy married colonial war privateer, Joseph Ashburn. The ceremony occurred at Old Swedes Church in Philadelphia. Betsy and Joseph Ashburn had two daughters: Zillah and Elizabeth, who died in her youth.

During the Revolutionary War, the Quakers split into fighting (Free) and pacifist wings. Betsy returned to her Quaker roots by joining the Free Quakers. The Free Quaker Meeting House, built after the war in 1783, still stands a few blocks from the Betsy Ross House.

In the winter of 1777, British soldiers occupied Philadelphia, and Betsy’s house quartered Red Coats. Meanwhile, the Continental Army suffered during the winter at Valley Forge, Pennsylvania.

The British captured Captain Ashburn during his trip to the West Indies. The journey to buy war supplies for the Revolutionary cause ended with Ashburn’s incarceration at Old Mill Prison in England. He died in March 1782, several months after Cornwallis surrendered at Yorktown, Virginia.

One of John Ashburn’s fellow prisoners, John Claypoole, an old friend of the Ross family, got released in a prisoner exchange after the war. He returned to Philadelphia in June 1782. Claypoole relayed the news of Joseph Ashburn’s death to his widow and her family. A Continental Army veteran of the Battles of Brandywine and Germantown. John Claypoole faced wounding at the Germantown and then expulsion from the army. He signed on to work on an American cargo ship, which the British captured on its way back from France.4

In May of 1783, Betsy married for the third time to John Claypoole at Christ Church. Betsy convinced John to abandon marine life, and he worked in Betsy’s upholstery business. After that, he worked at the U.S. Customs House in Philadelphia. Betsy and John had five daughters (Clarissa Sidney, Susannah, Rachel, Jane, and Harriet died at nine months).

After the birth of their second daughter, the Claypoole family moved to a larger home on Second Street. That area was the Philadelphia Mercantile District.

John passed in 1817 after years of ill health. Betsy never remarried and continued working until 1827. As a successful entrepreneur, many of her immediate family worked in Betsy’s business.

After retirement, Betsy ended up in the then-rural area of Abington, Pennsylvania north of Philadelphia. There, she lived with her married daughter Susannah Satterthwaite in the then-remote suburb.5 Betsy moved back to Philadelphia in 1835 to stay with another daughter, Jane Canby.

In 1834, only two Free Quakers attended the Meeting House. Betsy and Samuel Wetherill’s son John Price Wetherill realized their Meeting House had seen its last days as home to the Free Quakers. Betsy died on January 30, 1836, at the age of 84.

Betsy’s remains have been moved twice in Philadelphia since the initial burial. Initially, the interment occurred Free Quaker burial ground at South 5th St. near Locust St. The first move placed her at Mt. Moriah Cemetery. Betsy’s remains are now on Arch Street in the courtyard adjacent to the Betsy Ross House.

The Betsy Ross House

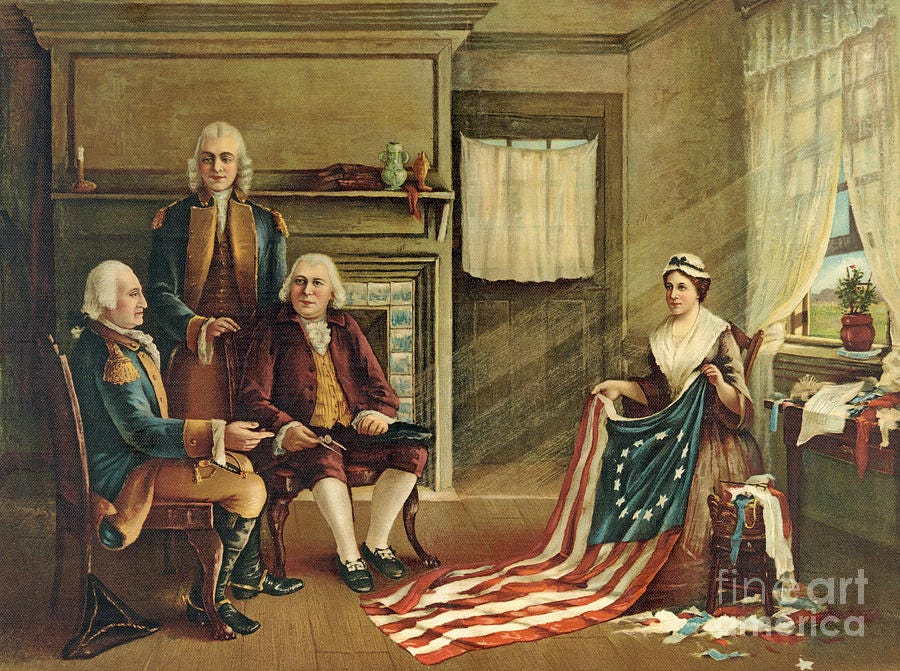

American Flag House and Betsy Ross Memorial Association, incorporated on June 14, 1898, sought funds to purchase and start a Betsy Ross House museum in Philadelphia. Founded by Charles H. Weisgerber of Philadelphia created the apocryphal much-reproduced life-size painting “Birth of Our Nation’s Flag.”6

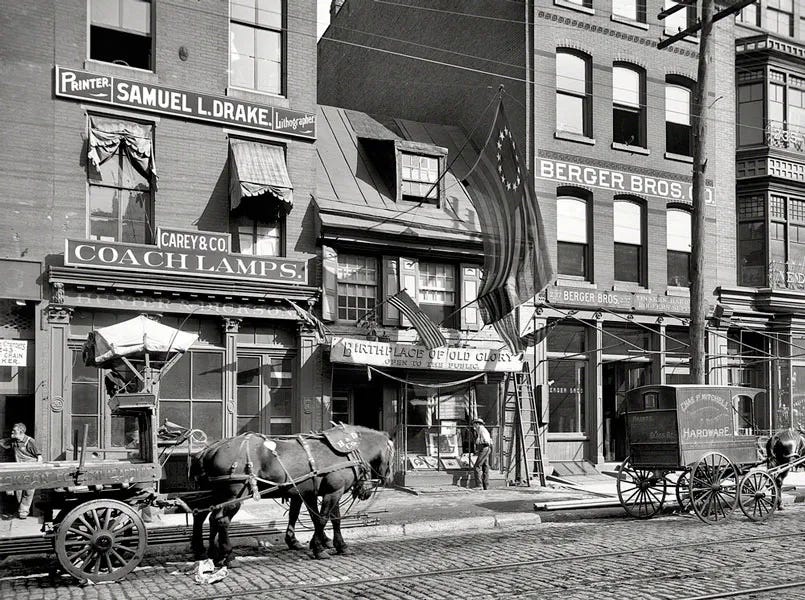

Weisgerber’s association’s objectives, as his promotional literature put it, were “to purchase and preserve the historic building, situated at No. 239 Arch Street, Philadelphia, Pa., in which the first flag of the United States of America was made by Betsy Ross and subsequently adopted by Congress, June 14th, 1777, and to erect a national memorial in honor of this illustrious woman.”

Weisgerber moved into the Betsy Ross House with his wife and brother around the turn of the century. Three years after gaining control of the house, Weisgerber tried to sell it to the federal government. A measure that would have made the house a government-run site to honor Betsy Ross was turned down by the House Committee on Public Buildings and Grounds in 1905. In 1907, Weisgerber tried, again without success, to give the house to the City of Philadelphia.

Weisgerber died in 1932, and his association went out of business three years later. The Betsy Ross house had seriously decayed during the three decades of Weisgerber’s ownership. Weisgerber’s association had raised and spent thousands of dollars purchasing and preserving the property, but funds to maintain the building proved scarce.

The savior of the house was A. Atwater Kent, who led a fund-raising effort to restore the building, which he donated to the city of Philadelphia in 1937.

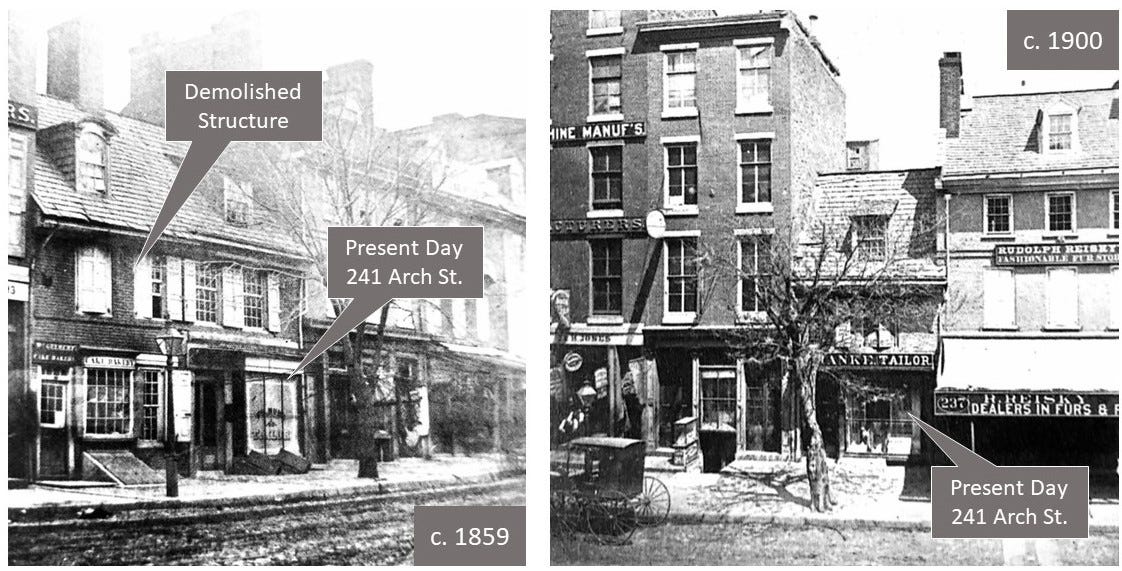

Visitors to the Betsy Ross House in Philadelphia may not visit the structure where Betsy Ross lived. The evidence showing the exact house on Arch Street where Betsy Ross lived is unclear. That is because Betsy Ross and her husbands rented and never owned the property. One document indicates that Elizabeth and John Claypoole lived at 335 Arch Street. With Philadelphia’s street-numbering system changed several times in the nineteenth century, the best that can be said with certainty is that Betsy Ross lived either at the present-day 241 Arch Street (existing rebuilt structure) or next door (demolished structure).

An Infuriating Back to the Future

In a sad and infuriating turn of events in recent years, the Betsy Ross flag, recognizable by many as the iconic banner featured in the painting Washington Crossing the Delaware, has come under attack. This flag, an emblem of the American War for Independence, has been labeled as racist and a symbol of slavery.7

More recently, the shorthand “2A” for the Second Amendment is now listed by the FBI as among the “Domestic Violent Terrorism Symbols.” They aver that “domestic extremist groups” or “anti-authority violent extremists” display the Betsy Ross Flag and the Gadsden Flag, among others. Not surprisingly, collectivist symbols, such as the hammer and sickle icon, are missing from the FBI’s list.

Historically, nefarious groups such as the KKK use symbols otherwise associated with good causes. People with common sense knew such associations were disconnected worldviews in the past. Today the government and nefarious groups such as the Southern Poverty Law Center push a collectivist narrative. That is the deliberate tagging of anything associated with true patriotism. Thus the Betsy Ross flag, in the mind of the fear peddlers and their manipulated-controlled masses, symbolizes fabricated hate. It is projected as a xenophobic icon at best and a white supremacy symbol at worst.

Sources

Books

Flag: An American Biography - Nelson DeMille, 352 pages, St. Martin’s Griffin, May 2006

The Rewriting of America’s History - Catherine Millard, 462 pages, Christian Pubins, January 1991

Online

Uhistory.com: Betsy Ross and the American Flag

History.com: Did Betsy Ross really make the first American flag?

Betsy’s Battle Flag, a poem by Minna Irving

Quaker is a member of the Religious Society of Friends.

Ross's descendants’ spoken and written words provide us with much of the information forming this story. Thus, some historians question the validity of the “Betsy Ross” flag without original and official documentation. Betsy’s story was first publicly relayed to the Historical Society of Pennsylvania nearly a century later, in 1870, by her grandson, William Canby.

Canby’s claim (which was supported by affidavits from Ross’s daughter, niece, and granddaughter) was published in “Harper’s New Monthly Magazine” in 1873 and soon became part of the United States history curriculum taught to millions of elementary-aged school children every year.

No original documentation has been found to confirm that Betsy Ross sew the first flag. Nevertheless, she likely was acquainted with both Washington and Morris. They were reported to have worshipped at the same church she attended. It has also been established that Ross made flags, as evidenced by a receipt for the sum of more than 14 pounds paid to her on May 29, 1777, by the Pennsylvania State Navy Board for making “ships colours.”

Also, see The History of the Flag of the United States by William Canby - A Paper read before the Historical Society of Pennsylvania (March 1870.

Abington Township, Pennsylvania, is an old stomping ground of your author.

Charles Weisgerber’s “Birth of Our Nation’s Flag” is not displayed in the Betsy Ross House. After the painting was vandalized while on exhibit in the old Pennsylvania State Museum in Harrisburg in the 1950s, it was placed in storage for more than four decades in a Delaware County, Pennsylvania, barn and later in a dye-making shop in southern New Jersey. The artist’ descendants offered the painting to the city, but Philadelphia officials declined to exhibit it in the city’s museums or other public buildings. After lundergoing a forty-thousand-dollar restoration in 2000—during which the painting was cleaned, remounted, and retouched—the family donated the painting to the State Museum of Pennsylvania in Harrisburg, where it is on exhibit today. “We wanted it to be in a place that would guarantee accessibility to the public and give it the protection it needs for the long term,” said the artist’s grandson, Charles Weisgerber II.

[John] Claypoole was a member of one of the first publicly recognized societies dedicated to anti-slavery principles in American history. “Claypoole, like many others, saw the paradox of a country founded on the ideals of the Declaration of Independence but practicing the tyranny of slavery,” said Mead. “Claypoole's story demonstrates that there were many people who were involved in the Revolution beyond those we learned about in school, and that some of those people actively sought to expand the Revolutionary promise of equality by working to end slavery. There are no ordinary lives and every one of these stories tells us important details about who we are as a nation and who we want to be.”

Subscribe to Frederick R. Smith Speaks

The Frederick R. Smith blog is the ramblings of an uncommon man in a post-modern world. As a master of few topics, your author desires to give readers a sense of the thoughts of a senior citizen who lived most of his life before the new normal.

Great job enlightening us. If people knew more about our Founders and the other people in our history like Betsy Ross they would begin to appreciate what was given to them and how much it cost. Then get off their asses and do something to keep it!

Betsy Ross is well known, or so we thought. my friend Frederick R. Smith is a historic storyteller. I hope you will find this chapter on the Women of the Revolutionary War fascinating and moving, and learn things we were not taught. There is much, much more to Betsy Ross than a simple seamstress who was chosen to make our New Nation's first Flag. But Fredrick brings it up today with his story. Be sure to watch the Videos. His first three chapters started on the 4th of July, Independence Day. I asks what role did women play, as they were varied and often dangerous. He chose Betsy Ross as his first Woman of the Revolutionary War. ENJOY!